Joker

Reviewed by Tony Keen 23-Oct-19

Joker is not a bad movie, nor is it unworthy of your attention. But it is not the work of genius that it so desperately wishes it were.

A couple of warnings: (1) There will be spoilers here; (2) This review is seemingly not in accord with a lot of fan and some critical opinion. Hey ho. Sometimes a corrective view is necessary.

A couple of warnings: (1) There will be spoilers here; (2) This review is seemingly not in accord with a lot of fan and some critical opinion. Hey ho. Sometimes a corrective view is necessary.

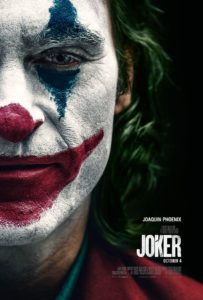

Over the years, there have been a lot of screen portrayals of Batman’s arch-nemesis the Joker, from Cesar Romero’s gentleman clown in the 1966 TV series, through Jack Nicholson’s pantomime murderer in 1989’s Batman and Heath Ledger’s psychopath in The Dark Knight, to the “what the hell was that?” of Jared Leto in Suicide Squad. And now here comes another, Joaquin Phoenix, in what is, within the increasingly complicated onscreen DC continuity, effectively an Elseworlds to the regular DCEU movies. Phoenix’s performance is certainly intense and interesting, though I would stop short of describing it as “extraordinary”. But the movie itself doesn’t quite gel.

Why not? The cinematography is excellent, and there are some fine set pieces, especially of the Joker chasing or being chased through Gotham City. It is graced by some nice performances besides Phoenix. Todd Phillips directs well, building a coherent narrative out of a screenplay cowritten with Scott Silver. There’s a neat, if underused, device of seeing into the Joker’s fantasy life. Yet Joker never quite lives up to the potential suggested by its remarkable trailers.

One element of the problem is that Phoenix is rather more impressive as Arthur Fleck, the mother-fixated man who will become the Joker, than as the full-fledged Clown Prince of Crime himself. In part, this is an inevitable consequence of telling a Joker origin story. This movie tells that story logically and plausibly, incident piling upon incident in a way that never loses the viewer, though neither is it ever particularly surprising – the story of a mentally ill man victimised and abandoned by both society and individuals, and conspired against by circumstance, until finally he snaps is familiar enough that audiences will see the movie’s trajectory even if they don’t know who the Joker is (and, frankly, the movie assumes they do). But the Joker, even the dishevelled Joker we have here, with imprecise make-up, is ultimately such an over-the-top cartoon character that some sense of realism is inevitably lost on the way to anyone becoming him.

Such a dichotomy between realistic origins and a cartoon outcome did not use to be a problem for Joker stories. The character notched up nearly fifty years with little attempt to explain his psychology. In the best Joker stories of that time, such as Steve Englehart and Marshall Rogers’ brilliant “The Laughing Fish” of 1978, he just is.

That all changed, of course, in 1988, with Alan Moore’s The Killing Joke, which made psychological approaches to the Joker de rigueur. (The other thing that has changed is that, through the likes of Stephen King’s Pennywise, the killer clown motif is now far more narratively prevalent.) Moore’s shadow lies very heavily over Joker, not least in its noir stylings, though this is an overtly 1980s noir, meticulously recreated to the point of using a 1980s Warners ident card. It’s also one in which much happens in daylight, raising an issue I have commented on before, that “Gotham at night can be the Art Deco-cum-Gothic fantasy metropolis of Bob Kane, Bill Finger and Jerry Robinson’s imaginings […, but b]y day, Gotham is all too obviously New York under a thin disguise.” However, this is something about which this particular movie does not care.

Moore’s disinclination to be associated with cinematic versions of his work is well-known, so it’s no surprise his name is nowhere in the credits, though his Killing Joke collaborator Brian Bolland is, in the “Special thanks” section which is code for “we’ve used your ideas, but as it was all work-for-hire, we won’t be paying you any money”. Odd in its absence from this section of the credits (unless I missed it) is the name of Frank Miller, from whose work several scenes in the movie draw.

But like all superhero movies, Joker has a magpie approach to previous versions, picking and choosing what aids its telling. From Tim Burton’s 1989 movie, Joker takes a connection between the Joker’s origins and the death of Batman’s father Thomas Wayne. To this it adds an unconfirmed familial relation between Fleck and Wayne, Sr, bringing in an Oedipal layer to the narrative. This potentially sets up either an intriguing wrinkle to the idea of Batman and the Joker being two sides of the same coin, or something dreadfully clichéd, in the highly unlikely event Phoenix can be persuaded to return for a sequel. Douglas Hodge’s Alfred Pennyworth, unnamed in dialogue but instantly recognisable, owes much to Sean Pertwee’s interpretation in Gotham. And there’s even a cheeky wink at the 1966 show.

It also must be said that this movie is quite right-wing. Of course, as I’ve said elsewhere, all superhero movies have right-wing tendencies, and Batman movies more than most, but even by those standards Joker is a bit out there.

True, it’s not the incel manifesto some had feared, though it does do the dangerous thing of inviting audience sympathy for a murderer – and it’s worth noting that, with the possible exception of his neighbour and her daughter, whose fate is left uncertain, everyone whom the Joker kills has done something to “deserve” it. This contrasts with the random slaughter perpetrated by the Joker of the comics.

Where the movie shows its colours is in its attitude towards capitalism. True, it admits that the system neglects many, and that some, perhaps even many, capitalists are bad. And it’s interesting that Joker places Thomas Wayne amongst those, highlighting that the common view of Wayne as a paragon comes from a son that idolised him but never really knew him.

But Phillips himself is hostile to the far left, and the movie’s overt message is that grassroots anti-capitalist movements are far worse than capitalist rotten apples. Much more hostile to these groups than Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Rises, Joker portrays them as violent and destructive, and too ready to follow a charismatic but evil leader. It’s not surprising that the movie appeals to those who see the Antifa movement as being as bad as the Nazis they oppose. This may not be an out-and-out endorsement of the far right, but despite some claims, neither is it some Bernie Bros attack on the system that brought us austerity.

However, the real problem here is that while Joker invites such political readings, it cannot then bear their weight. It never manages to resolve the inherent tensions in being, as a friend described it on social media, “gritty fluff”. As Logan did in 2017, Joker seeks to push at the envelope of the superhero movie. But for all its depth and characterisation, Logan never forgot it was an X-Men movie. Joker, in contrast, seems positively ashamed of its origins in the Batman franchise, and seeks to deny that it is any sort of superhero exercise (Thomas Wayne is given a line condemning hiding behind a mask, exactly what his son will go on to do). This is utterly conscious; Phillips has stated that his intention was “to sneak a real movie in the studio system under the guise of a comic book film”. He wants to make a psychological thriller; hence the overall pessimism of the movie, in contrast to the generally sunnier disposition of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Specifically, Phillips wants to make a Martin Scorsese psychological thriller. Hence no-one much cares that Gotham looks just like New York – it’s meant to be a thinly-disguised NYC. There are obvious thematic links to Taxi Driver (1976), but the biggest homage is towards 1982’s The King of Comedy. The idea of a climax in a TV chat show probably originated in Miller’s Dark Knight Returns, but the casting of Robert De Niro, the movie’s only other “name”, as host Murray Franklin makes the link to Scorsese’s movie explicit, with De Niro in the Jerry Lewis role, and the Joker as the dangerously obsessive fan previously played by De Niro.

Specifically, Phillips wants to make a Martin Scorsese psychological thriller. Hence no-one much cares that Gotham looks just like New York – it’s meant to be a thinly-disguised NYC. There are obvious thematic links to Taxi Driver (1976), but the biggest homage is towards 1982’s The King of Comedy. The idea of a climax in a TV chat show probably originated in Miller’s Dark Knight Returns, but the casting of Robert De Niro, the movie’s only other “name”, as host Murray Franklin makes the link to Scorsese’s movie explicit, with De Niro in the Jerry Lewis role, and the Joker as the dangerously obsessive fan previously played by De Niro.

Phillips has certainly learnt from the master. Gotham/New York is appropriately grim, shabby and rundown. There’s effective use of pre-existing popular music, blended with a haunting original soundtrack by Hildur Guðnadóttir, though someone should have stopped the disastrous inclusion of Gary Glitter’s “Rock and Roll (Part Two)” – yes, it works in context, but so would several other songs that don’t have such unpleasant wider connotations.

Yet all these stylings give the sense that such terms as “Gotham”, “Wayne” and “Joker” could easily be removed from this movie without significantly changing it. Joker seems to be all about the surface gloss – the trouble is, beneath that surface, the substance of Joker is, as Ani Blundel and others have said, ultimately rather hollow. This is why, though many fans have taken to the movie with enthusiasm, and it has a very healthy box-office, some critical response has been less friendly.

None of this critique is to say that Joker is a bad movie, or unworthy of your attention (though some, such as Blundel, have argued that). It is better than any DCEU movie with the exception of Wonder Woman (not that that’s a particularly high bar). It’s a superior superhero/supervillain flick – if not up there with the likes of Logan or Dark Knight, nor even the best superhero movie of the year (which is, obviously, Captain Marvel, in case you were wondering), at least as good as the last two Avengers movies. Phoenix’s Joker is better than Nicholson’s or Leto’s, though can’t match Ledger’s (Romero’s is so much a product of a different style and age that it just isn’t comparable). But Joker is not the work of genius that it so desperately wishes it were.

Tags: Batman, DC, Joaquin Phoenix, Joker, movie reviews, Scott Silver, superhero movies, Todd Phillips, Warner Brothers

I managed to forget to mention the clear echoes of Network and Albert Finney’s rant at the world in Joker’s final scenes.

I’m not remotely surprised by Joacquin Phoenix’s Oscar nomination for Joker – it’s exactly the sort of physically transformative performance (usually through make-up, in this case through diet) that attracts the Academy’s attention. And Best Picture and Director ride on the back of the whole idea of ‘let’s do a proper auteur movie and pretend it’s superheroes’, which appeals to anyone who hasn’t noticed that Winter Soldier is basically an Alan J. Pakula movie (and integrates the two approaches, political thriller and superhero, rather better than Joker does with the ‘mean streets of New York’ approach). I expect Phoenix will win, and I’m sure Joker will take away Make-up and Costume Design, and has a good chance for best score. Competition may be rather stiffer in other categories. I expect Scorsese will win Best Director, as it’s probably the last chance to give him one, Little Women will take Best Adapted Screenplay, and I can’t call Best Picture, but don’t think it’ll be Joker.