The Best of British: Swift

by Win Wiacek 27-Apr-12

Swift was the fourth title to emerge from the Hulton Press stable under the auspices of the Reverend Malcolm Morris as part of his crusade to produce high quality, morally uplifting comics for children. Whilst never to gain the giddy heights achieved by Eagle, it joined secondary titles Girl and Robin, and was a publication which targeted the then-untapped audience between pre-schoolers and independent readers, completing for Hulton a slick and colourful line of publications which catered to all “good and decent” children from the cradle to adulthood.

[Welcome to what we hope will become an occasional feature surveying the history of the British comics field. While certain British titles have had extended critical review and acknowledgement (Beano, Eagle, 2000 AD), the vast majority of the industry’s history and product remains under-researched, with many series and creators waiting to be properly appreciated. We begin with Win Wiacek’s retrospective on the often-overlooked junior sibling of the acclaimed Eagle weekly. – WM]

[Welcome to what we hope will become an occasional feature surveying the history of the British comics field. While certain British titles have had extended critical review and acknowledgement (Beano, Eagle, 2000 AD), the vast majority of the industry’s history and product remains under-researched, with many series and creators waiting to be properly appreciated. We begin with Win Wiacek’s retrospective on the often-overlooked junior sibling of the acclaimed Eagle weekly. – WM]

Swift was the fourth title to emerge from the Hulton Press stable under the auspices of the Reverend Malcolm Morris as part of his crusade to produce high quality, morally uplifting comics for children. Whilst never to gain the giddy heights achieved by Eagle, it joined secondary titles Girl (“sister paper” first published 2nd November 1951) and Robin (“for young children”, 28th March 1953), and was a publication which targeted the then-untapped audience between pre-schoolers and independent readers, completing for Hulton a slick and colourful line of publications which catered to all “good and decent” children from the cradle to adulthood.

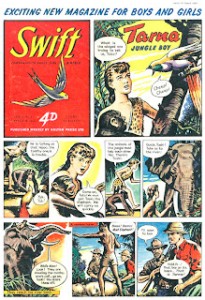

Swift first fell into young hands on 20th March 1954, with the signature logo, design and colours that reiterated a reputation of wholesome quality to parents. First sight was the brightly coloured Tarna, Jungle Boy as the front-page feature. Company policy was always to lead with an Ace (Dan Dare in Eagle, Kitty Hawke and her All-Girl Air Crew in Girl, television “star” Andy Pandy in Robin), and the arresting artwork of Harry Bishop (who would go on to draw Gun Law, an adaptation of TV’s Gunsmoke for the Daily Express) used the lush possibilities of the photo-gravure printing process to marvellous effect.

Tarna was a good-hearted junior Tarzan knock-off, wandering through the mythical Africa which should have existed but sadly never did, making friends and having adventures with his faithful chimpanzee Toto beside him. They would hold pole position for five years before being moved inside and demoted to monochrome. This was no real shock for readers, as the second page, comprising the top half of the inside front cover, had always been black and white, originally pen and ink but soon the half-tone wash blend which added so much atmosphere to the interior pages of the Hulton titles. The remainder of the page was a two-tier cartoon short, beginning with the short-lived but charming Mono the Moon Man, soon replaced by Roddy the Road Scout, which ran until 1961.

Tarna began as an innocuous pastiche of jungle adventurers, rescuing his fair share of little girls lost in the underbrush, visiting lost and subterranean kingdoms, and thwarting mildly evil white hunters in pretty but largely thrill-free tales, until Morris was replaced as editor by Clifford Makins in October 1959 (Vol. 6 #38). From then an edge crept into the stories and by the time the comic was incorporated into Eagle (Vol. 10 #9, 2nd March 1963) Tarna was a grown man, chucking villains off cliffs and in all ways indistinguishable from the Edgar Rice Burroughs prototype. He had lost the cover spot in 1958 to Smiley, a nondescript strip – despite some outstanding artwork – relating the Outback adventures of an Australian boy.

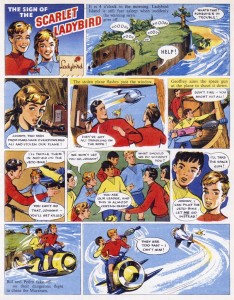

The back covers had one of the earliest examples of “Infomercial”. A serial originally produced by Pasolds and Canning related the exploits and travels of Johnny and Brenda (and eventually Bill), members in good standing of the Ladybird club, apparently the paramilitary fan-club wing of Ladybird Books. The Sign of the Scarlet Ladybird, termed an “advertising announcement”, took the kids around the world, and beyond it, where they met other club members (identifiable by the designer label on their sweaters, T-shirts or dressing gowns – all available from better clothing emporia – just ask Mother to buy you one!) to deliver them from whatever generally benign straits they found themselves in. They even went to Mars and met Spaceboy (a fellow clubber, naturally).

I would love to know who paid who for this ad, as it ran in some form, almost without interruption, until a major overhaul repositioned the comic in the same age bracket as older brother Eagle in 1961. It should also be noted that the strip, although produced under the multiple handicaps of having to be wholesome and entertaining enough to satisfy the editor and forceful enough for Ladybird’s advertising department, was a beautiful piece of children’s fiction, which promoted the clothing line, not publications. Another infotainment that ran and ran was Then and Now, a history strip from the Gas Council featuring the comedy antics of an anthropomorphic flame called Mr. Therm.

As the publication settled into its stride, there were early casualties, including the excellent Sir Boldasbrass, a full colour strip for the centre-spread by John (Captain Pugwash, Harris Tweed) Ryan, which was replaced by The Rolling Stones, a strip about circus children, and Sally of Fern Farm. The Fleet Family, a take on Swiss Family Robinson set in the Australian Outback, was promptly superseded by an adaptation of the original classic. Ryan would briefly return in 1959 with a full colour Pugwash series, when Pugwash was a TV star in his own right.

Despite an established British history of deriving comic strips from stage, screen and radio sources, Hulton in many ways consolidated today’s inescapable bond between comics and the other media which pervade children’s formative years. As well as the previously cited examples, Swift had strips and features based on entertainment personalities Peter Butterworth and Jimmy Hanley, the ventriloquist act Educating Archie with Peter Brough, and Dixon of Dock Green – which began as an interior strip (Vol. 4 #51) and graduated to the cover position when the comic reformatted itself to Eagle’s tabloid dimensions (Vol. 7 #15, 9th April 1960). The western Wells Fargo by Don Lawrence migrated from Zip when it amalgamated with Swift (Vol. 6 #36, 10th October 1959).

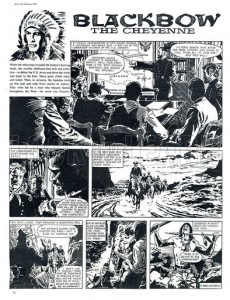

Before Trigan Empire and Storm, Lawrence had a long association with Swift and drew a number of the many cowboy strips which proliferated during the 1950s and 1960s television boom. He handled Pony Express (Vol. 8 #1-40, January – September 1961) and Blackbow the Cheyenne. Other westerns of note included Tom Tex, Pinto and Buckskin (Vol. 1 #1), Cliff McCoy, and Slicker, illustrated by Jim Holdaway (Vol. 2 #33), who also handled the Canadian Mountie Red Rider (Vol. 3 #13). Roland Davies drew Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshal.

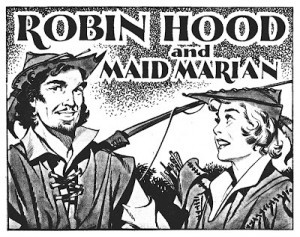

Frank Bellamy moved from Mickey Mouse Weekly to illustrate The Fleet Family and Swiss Family Robinson before taking over Paul English from George Bellavitis, all in the first year of publication. King Arthur and his Knights, written by editor-in-waiting Clifford Makins (Vol. 2 #31), came next before he moved on to Robin Hood and his Merry Men (Vol. 3 #18, 12th May 1956), which became Robin Hood and Maid Marian. Bellamy then moved over to Eagle to work on The Happy Warrior and cement his growing reputation.

Frank Bellamy moved from Mickey Mouse Weekly to illustrate The Fleet Family and Swiss Family Robinson before taking over Paul English from George Bellavitis, all in the first year of publication. King Arthur and his Knights, written by editor-in-waiting Clifford Makins (Vol. 2 #31), came next before he moved on to Robin Hood and his Merry Men (Vol. 3 #18, 12th May 1956), which became Robin Hood and Maid Marian. Bellamy then moved over to Eagle to work on The Happy Warrior and cement his growing reputation.

The early missionary influence of Morris, which seemed to disproportionately favour education (albeit beautifully rendered) over entertainment, gradually waned. The 16-page weekly lost Famous People of Today and Things to Do as well as Educating Archie, and the centre-spread pictorials (junior equivalents to the technical cutaways beloved of Eagle readers) tried many variations before settling on travelogue style paintings of This Wonderful World and In Other Lands. A text serial, The Magic Penknife, replaced stand-alone prose stories, and the selection of general interest features moved towards more traditional editorial page-fillers such as quizzes, pet photos and competitions. This retained a required balance of text to pictures that acted as a nod to critics who decried the very existence of comics as being damaging to children who were learning to read. Unlike Eagle, word balloons in Swift were lettered in lower case and captions were typeset, presumably for the same reasons. There was, naturally, the mandatory inspirational biblical strip, The Boy David, which evolved into David and Jonathan before resolving into a parade of tales of saints and worthy souls.

Strips like Sue Carter (a plucky young girl wandering the world with her little brother), Nicky Nobody and his dog, Chum (schoolboy orphan), Sammy (ordinary lad having extraordinary adventures – including a cross-over with Eagle’s Space Fleet in Sammy and the Space Bandits, Vol. 5 #18 – #27, May – July 1958), Tom Tex, and the turgid but wonderfully illustrated Paul English (a cabin boy who sailed with Raleigh, and latterly Sir William Maitland, to the New World in search of his lost father), ran for years, whilst adaptations of classic books, perennial re-workings of school stories (Ginger and Co., Merrick of Merryhill or The Hero of Blackstone School), and original strips of English worthies like The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Son of Drake and Pilgrim’s Progress, came and went.

Most notable are such humour strips as The Bentine Bumblies, a manic series of misadventures of someone who looks awfully like Ex-Goon Michael Bentine, on a planet of weird creatures that seem to be a precursor to both the Mister Men and the Smurfs. Eventually Bentine returns to Earth with a trio of aliens who promptly ditch him in favour of three children for the duration. The Bouncers, by Peter Maddocks, were a band of mad-cap, legless aliens whose antics presaged the camp psychedelia of the mid-1960s. Of final note from these years is Our Gang, a rather traditional strip about three mischievous kids (better suited, perhaps, to Beano or Dandy) produced with style and wit by renowned cartoonist Harcourt Dennis Mallett. It seems oddly out of place in its setting, yet only Tarna ran longer than this lost gem.

When the last overhaul was completed during the ninth volume, Swift became a de facto boy’s comic with science features, cars, paintings of jets on the cover and action strips such as The Phantom Patrol (reprinted extensively in 2000 AD annuals) and The Happy Hussar, complementing Blackbow and Tarna.

A comparative latecomer to Swift, the beautifully-illustrated Blackbow was one of the few strips to survive the merger with older brother Eagle.

Gone were the final vestiges of a junior and unisex approach, although much of the female component had already been relegated to text features – contemporary editorial wisdom held that girls stopped looking at drawings much sooner than boys – and despite an enviable record of quality work and a roster of creators which read like a who’s who of British artists (Cecil Orr, Reg Parlett, Eric Parker and Derek Eyles were among many who joined the aforementioned creators during its ten-year run) the comic suffered the usual fate of failing comics in the United Kingdom.

With Volume 10, # 9, it was incorporated into the tenth issue of Eagle’s Volume 14. Along the way it had produced more than 450 slim, colourful issues, nine annuals, a number of book tie-ins, and, hopefully, one or two good and decent, bright young people.

Swift: 477 issues, 20th March 1954 – 2nd March 1963; absorbed Zip (4th Jan 1958 – 3rd Oct 1959 – Odhams) from 10th Oct 1959, merged into Eagle 9th March 1963.

9 annuals 1955 – 1963

Swift Picture Books: Nick Nobody and the Rocket Spies 1960

Smiley Roams the Road 1960

The White Hart Lane Mystery (Dixon of Dock Green) 1960

Wild Birds and Animals of Britain 1960

Aircraft 1960

Trains and Cars 1960

Swift Book of Pets, Swift Book of Buses, Coaches and Lorries

Published by Hulton Press/Longacre Press

Really enjoyed this article. Good on you for looking into the history of British comics – I’m only really getting started, but the quality of a lot of the art was stunning, and the people behind it deserve to be better known.

Speaking as a retailer, Patrick, I’ve only really become at all knowledgable in the British comics field in the 10 years or so 30th Century Comics has been trading in them – and I have to say it’s been a revelation, seeing top-notch work in the most unexpected places (‘Glory Knight, Time-travelling Courier’ in June & School friend, by John M. Burns – delightful!). We certainly hope to spotlight more of incredibly rich & diverse legacy of British comics here in FA in the future.

Although it was less “edgy” than the Beano and its Thomson stable-mates, “Swift” still has many fond memories for me.”Our Gang” certainly deserves to be better known. Dennis Mallet’s artwork featured an incredible variety of facial expressions and some truly memorable sound-effects.

The look of that strip is curiously timeless (unlike the Bash Street Kids, still stuck in their early 1950s clobber), Tubby’s a mite old-fashioned, it’s true – what kid nowadays sports a blazer for everyday wear? – but Teena’s outfit of striped top and cut-off jeans, still looks bang up-to-date. And as for her brother Tich, with his beanie hat and dungarees …

Thank you for sharing your love of comics, in this case UK’s SWIFT. I was wondering if you know if someone has published a chronoly of Don Lawrence’s WELLS FARGO. I have The Book Palace compilation but unfortunately it doesn’t have any dates. Also, there is a Dutch site with some dates but it is incomplete. Thamks again for your attention.

I was born in 1952 so my memories of “Swift” begin around 1958 and are patchy.

I’d love to know what happened to Tarna’s girlfriend Peggy, and also how “Max Bravo” concluded.

I’ve managed to collect a few 1962 issues but none later.