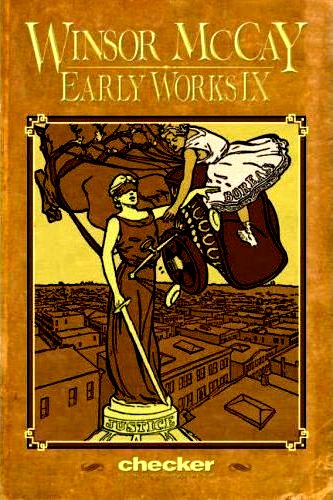

Winsor McCay: Early Works IX

Reviewed by Martin Skidmore 07-Feb-11

I’ve never been as big a fan of McCay as most comic fans are. I do see their point, and his massive importance is completely obvious, but I find most of his work a slog to read.

I’ve never been as big a fan of McCay as most comic fans are. I do see their point, and his massive importance is completely obvious, but I find most of his work a slog to read. He had something of a tin ear, not helped by what appears to be the practice of drawing the strips and inserting word balloons before doing the scripting. He ends up padding many very badly, with characters repeating themselves with slight rephrasing panel after panel. He pads individual balloons with “Oh! Oh! Oh!” and the like to make the text fit. At times he can’t make the words fit, and they get tiny and curl up and around, or simply continue in the next panel, wrecking any sense of rhythm.

This is hindered further by the bizarrely useless publisher. Yes, they put out top class material (I have some of their Caniff collections too) at reasonable prices (170 odd pages here, $20 cover price), but they do it very shoddily. The Saturday pages here, which I believe were half a newspaper page when originally published, are printed here at comic-book page size, and combined with the often very poor quality of the images or printing, this makes them almost unreadable – I actually needed to dig out a magnifying lens (which I had bought several years ago when I had severe eye problems) for the first time in years for some strips here. The contextualising is hopeless too – an unreadable one-page intro, all in upper case FFS; and sequences of old strips and editorial drawings, without any dates. Obviously for comedy strips this is just a matter of historical context for comics obsessives, though that is surely a big part of the audience for this, but for the editorial work, some context is vital simply to have a clue what some of the drawings are getting at (some are plainly WWI, some early prohibition, so 1920 and soon after, but some I couldn’t understand at all). We also get 38 pages of cels from McCay’s classic and pioneering ‘Gertie the Dinosaur’ strip – all printed across spreads, and since he almost invariably put the action in the middle, this doesn’t work terribly well.

But having moaned about the publisher and the actual words, let’s address why McCay is so revered. This volume is mostly Dream of the Rarebit Fiend strips, his second greatest work (there’s no Nemo in this series at all, in the several volumes I have). A lot of them are pretty tedious and routine and spectacularly badly paced, but some are absolute unquestionable masterpieces. I was stunned by many of them (and it’s great to see 30 of them in full colour), by the pre-surrealist imagination, but especially by his sense of design, which was surely the major influence on the more totally lovable Cliff Sterrett some years later. It’s not just the modern deco look mixed with the dreamlike moments, it’s his sense of visual rhythms too – page 19 here has that in a way that reminds me strongly of the magnificent Polly strip Jonathan Bogart linked in his recent review – I wish I could tell you the date of the Rarebit strip I mean. Some of the editorial cartooning is immensely impressive too, powerfully composed and beautifully drawn to make a potent point. On a purely visual aesthetic level, his best work stands alongside anything ever produced in comics – and yes, I accept that that is easily sufficient to justify his enormous standing in the artform, but sadly I still find him mostly very unsatisfying to actually read rather than just look at.

Tags: Checker, newspaper strips, Winsor McCay