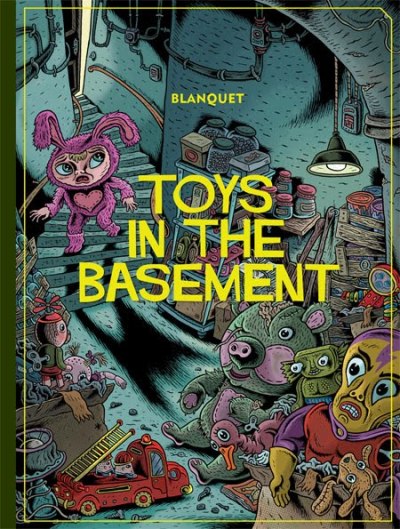

Toys in the Basement

Reviewed by Peter Campbell 20-May-11

Stephane Blanquet has been an active figure in the French comics field since the early 90s. He’s a prominent figure in a movement that’s been given various names: “baby art”, “art brut”, “visionary art”. In a comics context it’s one of those movements that difficult to define, but easy to recognise when it’s seen. It draws on illustrations in Victorian children’s books, underground comics, 1950s pre-code horror comics and the actual style of drawings made by children, and blends the lot into something typically rather grotesque and disturbing.

Stephane Blanquet has been an active figure in the French comics field since the early 90s. He’s a prominent figure in a movement that’s been given various names: “baby art”, “art brut”, “visionary art”. In a comics context it’s one of those movements that difficult to define, but easy to recognise when it’s seen. It draws on illustrations in Victorian children’s books, underground comics, 1950s pre-code horror comics and the actual style of drawings made by children, and blends the lot into something typically rather grotesque and disturbing. This movement hasn’t broken into US mainstream comics yet, which makes the publication of this book something of a landmark. At the same time, this is aimed at children, which makes it a rather atypical work.

It’s also, at 32 pages, a slim book, though, as is usual these days with Fantagraphics’ releases, it’s beautifully presented in a full colour, oversized hardback volume. Thematically it covers familiar ground. Two children are among the guests at a children’s costume party. Dressed in rabbit costumes, they discover that broken and maltreated toys have taken refuge in the house’s basement. Mistaken as toys themselves, they are drawn into the toys’ world which turns out to be a not entirely welcoming, and sometimes downright threatening, environment.

Reading this, it’s impossible to escape a strong sense of déjà vu. Many of the same themes and situations presented here also appeared in Toy Story 3, and although this predates that film’s release by several years, it’s difficult not to make comparisons. This a considerably more threatening world, with its vertiginous perspectives and its frankly creepy toys (the unravelling threads from a teddy’s eye resemble maggots and the stuffing bulging from its head’s ripped seams resemble brains) What it lacks though is that film’s sharp invention. It has a rather generic and plodding storyline that culminates in an it-was-all-a-dream…or was it? scenario. And yes, it’s aimed at children, but that’s no excuse for such a shoddy piece of plotting.

The main interest here comes from the art. Blanquet’s clearly versed in the language of comics, and it’s possible to easily pick out his influences: those heads? Very Victor Moscoso. The twisted, expressionist bodies? Julie Doucett. The pervasive sense of unease? Pure Charles Burns. Those spiralling lines expressing bewilderment? Herge, surely. At the same time it doesn’t quite look like any of those artists. It’s always striking, but there’s not always a great sense of cohesion between the panels on the page, as though it’s been conceived as a series of separate illustrations rather than thought of as a cohesive page of comic art. And from this, and examples seen elsewhere, I think illustration is where Blanquet’s real forte lies.

I can’t see many children reading this – it’s a little too out of the mainstream and dark. At the same time, for adults, it’s a perilously thin storyline accompanied by artwork that doesn’t really show Blanquet’s creative abilities in full grotesque flight. A follow up volume featuring more representative material would be welcome, and while this is an interesting teaser, it’s hardly essential reading.

Tags: European, Fantagraphics, Stephane Blanquet