The Extremist

Reviewed by Ian Moore 08-Dec-10

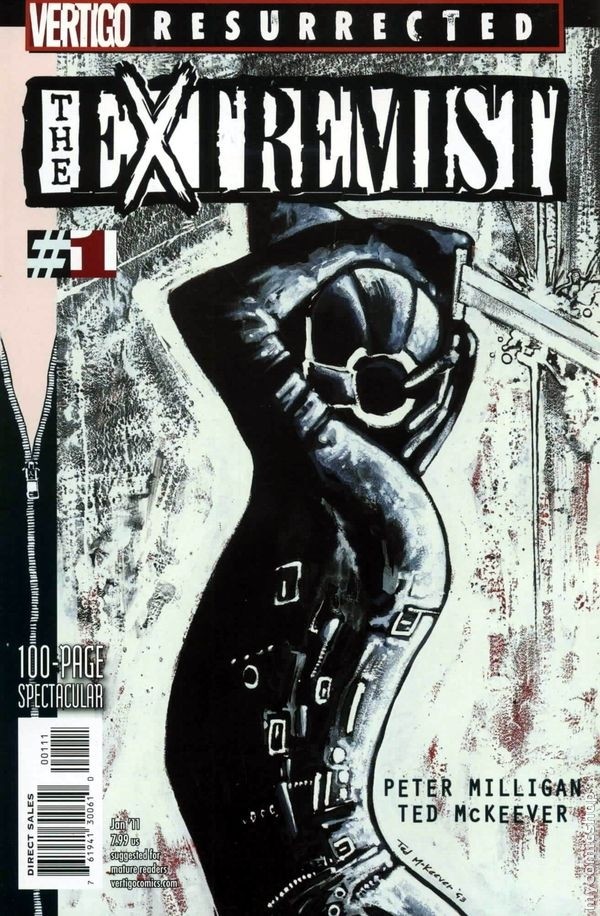

The Extremist was a four issue limited series from Vertigo in the early 1990s that they have now reissued as part of their Vertigo Resurrected line. Set in San Francisco, the book concerns itself with the Order, an organisation of Sadeans with outré sexual urges.

The Extremist was a four issue limited series from Vertigo in the early 1990s that they have now reissued as part of their Vertigo Resurrected line. Set in San Francisco, the book concerns itself with the Order, an organisation of Sadeans with outré sexual urges. The Extremist is the Order’s gimp-suited enforcer who deals with members who go too far or who threaten the organisation’s continued existence in any other way. By “deal with” I mean kill. The first part of the story follows a woman called Judy, whose husband was murdered in front of her. After his death she discovered his membership of the Order and then that he was the Extremist. She takes on the role of the Extremist as a way of trying to find her husband’s killer. But of course, in the best erotic thriller fashion, she then starts to uncover a dark side to herself that she never thought existed.

With the plot stated so baldly it would be easy to imagine that The Extremist is just another tawdry smut-fest. A couple of things succeed in lifting it above the ordinary. The story’s fractured time sequence and shifting point-of-view serve to lift it somewhat out of the ordinary – while the first part follows Judy as she finds herself sinking deeper into the role of the Extremist and drawing ever closer to her husband’s killer, the second jumps back to show us her husband, Jack, in the last days before his death as he becomes increasingly detached from the Order, his role as its enforcer, and from Patrick, the smooth talking aesthete who directs the Extremist. Then the third part jumps back to focusing on Judy in the aftermath of her husband’s death, while the last switches track completely to focus on a character who until then had been a minor presence in the background. When originally published, each break happened with a new issue, but here they run into each other. I think making the shifts more obviously pronounced worked better, as the current formatting seems to underemphasise them.

What is maybe interesting is that the book never focuses directly on Patrick. We only see him in so far as he relates to Judy and Jack. This leaves him as something of a phantom, a spokesman for decadence mouthing epigrams, reminiscent of one of Oscar Wilde’s literary self-portraits (yet drawn almost to resemble musician and artist Momus, probably coincidentally). Yet he seems to possess almost supernatural qualities, apparently dying and being resurrected at one point (something he dismisses as a parlour trick). Even if he is not literally the Devil, Patrick has demonic attributes and serves to lure the book’s characters deeper into vice and his world of oddly Nietzschean sexuality. Discovering that he was just some random guy who had got into S&M after being spanked too much by his mum would rather tarnish his allure, so it was wise of Milligan to leave him as a mysterious blank page.

The other winning feature of this book is the art. McKeever has never been the most photorealistic of artists. Here his work has a kind of expressionist quality that calls to mind German silent films of the 1920s. That gives the book a certain nightmarish quality that suits its universe-next-door storyline. The art serves one other useful purpose – by being actively non-realistic it makes the various orgy scenes just seem weird and strange instead of saucy and straightforwardly erotic, keeping The Extremist away becoming just a titillating smutfest for the more onanistically inclined comics reader. McKeever’s art should nevertheless not be thought of as being crudely unrepresentational or lacking in detail – he displays a deft ability to convey the character’s moods through their changing facial expressions. The characters also manage to look quite different from each other – though as one of the four main characters is a black man, another a woman, and only the other two are white men this is not too difficult.

The Extremist nevertheless has some problems (or at least odd features). One of these is the basic premise – why does the Order need a murderous enforcer? San Francisco is a city with plenty of hardcore S&M clubs, but my understanding is that none of them feel obliged to kill any of their habitués who step beyond some blurry line of what is considered acceptable or who might in some way bring disrepute on the club. Then there is the book’s assumption that both the Order and Patrick, its decadent spokesman, are seductive. As a reader of comics I am not really in a position to scoff at the funny hobbies of others, but it does seem like Patrick is able a bit too easily to lure Judy into his world of polyamorous extreme sexuality. Sure, there are people who are into this kind of thing, but most people are not, and when we see Judy’s past life from before her husband was killed there is nothing to particularly suggest that she has always harboured a desire to embrace such a life-style. With Patrick we pretty much just have to take as a given that he is capable of seducing anyone into doing anything – it is like this is his superpower. Once that is accepted, Judy’s descent into the Order is a little easier to swallow.

Quirks aside, The Extremist remains an impressive piece of work, one I am glad to see available again after a long period in the wilderness of out of print comics of yesteryear.

Tags: DC, Peter Milligan, Ted McKeever, Vertigo