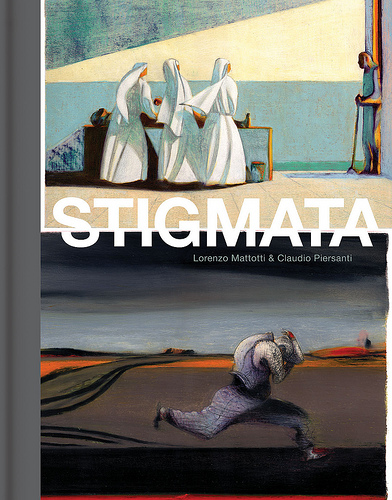

Stigmata

Reviewed by Peter Campbell 22-Mar-11

When Lorenzo Matotti’s Fires appeared 25 years ago, it was one those unexpected works that redefined what comics are capable of. It brought a painter’s sensibility to comics, and a sense of ambiguity that was rare in the medium. If I had to compile some sort of imaginary list of comics to take with me to a desert island, I’d still number it among my top ten. Since then, translations of his comics have been rare and, perhaps inevitably, none have recaptured Fires’ impact and unreal quality. Stigmata comes close to equalling that work though, and in some ways perhaps surpasses it.

When Lorenzo Matotti’s Fires appeared 25 years ago, it was one those unexpected works that redefined what comics are capable of. It brought a painter’s sensibility to comics, and a sense of ambiguity that was rare in the medium. If I had to compile some sort of imaginary list of comics to take with me to a desert island, I’d still number it among my top ten. Since then, translations of his comics have been rare and, perhaps inevitably, none have recaptured Fires‘ impact and unreal quality. Stigmata comes close to equalling that work though, and in some ways perhaps surpasses it.

The unnamed narrator of Stigmata is an alcoholic low-life. Following a dream in which he encounters a child (or God, or both) he wakes suffering from stigmata in the palms of his hands. He’s not religious, although some people come to see him as a saintly figure, and certainly one who is gifted, possessing healing powers. Not that the narrator sees it that way: he rages both against his followers and his detractors, and is put through a series of worsening ordeals, against which there is little respite. Even those moments of respite only serve to make the subsequent ordeals even more unbearable. By the end he reaches some sort of reconciliation with the events that have overtaken his life, but the events themselves remain inexplicable.

This is all pretty bleak stuff. I’m unaware of writer Claudio Piersanti’s other work, but this has all the grim opaqueness of a Robert Bresson movie. Tellingly, perhaps, Piersanti is not only a novelist, but a screenwriter. As with other writers with whom Mattotti has chosen to collaborate, it’s a highly ambivalent piece. Although there are suggestions throughout of design, and spiritual redemption, the events that occur could equally be attributed to chance and may, ultimately, be meaningless.

It’s Mattotti though who takes this core material and turns it into something extraordinary. He’s abandoned the soft, painted style he’s come to be associated with, and in its place is frenzied pen and ink that resembles a psychotic Francis Bacon on speed. Many, if not all, of the pages on view here appear to have been drawn in a single sitting, with a loose amorphous quality that gives the art a spontaneous, almost manic feel. He’s also switched from colour to black and white.

This has two noticeable effects: firstly, it gains narrative drive. In some scenes, as the emotional intensity increases, the crosshatching in the panels becomes increasingly dense, more abstract and, here’s the thing, it never loses its comprehensibility and drive. The other is that Mattotti’s influences become more apparent. In the faces, particularly, you can see the echo of Jose Munoz’s anguished, emotionally isolated characters.

There are some fantastically powerful moments: the attack by youths on a vagrant; a further attack on the narrator by his ex-employer and, at the book’s core, a long, sustained scene where a storm devastates the carnival in which the narrator’s taken refuge. It’s not only physically devastating; it’s emotionally devastating too.

For me, the one false note throughout was the scene where the character learns to accept his lot, and gains some semblance of emotional equilibrium, by reading a book of hymns. It seemed too pat a resolution after everything he’d been through. On a second reading, you could also interpret it as his character clutching at something – anything! – to give him relief, a viewpoint that fits much more comfortably with my base and pessimistic view of humanity.

Full marks to Fantagraphics for bringing this remarkable comic into the reach of an English-speaking audience, and especial praise for Kim Thomson’s translation which manages to avoid the stilted quality that so often dogs translated comics. This comes unreservedly recommended.

Tags: Claudio Piersanti, European, Fantagraphics, Lorenzo Mattotti

I have a vivid memory not just of first reading ‘Fires’ but first reading about it, when Martin reviewed it in the original old-school FA! Yes it was a game-changer. Haven’t read this latest one yet, but definitely intend to!

I was lucky enough to see Mattotti interviewed by Paul Gravett and David McKean in London a couple of weeks ago. Hopefully someone will podcast it. Regarding your point about Piersanti being a screenwriter, it seems ‘Stigmata’ was first planned as a film.