Paying For It

Reviewed by Peter Campbell 09-Jun-11

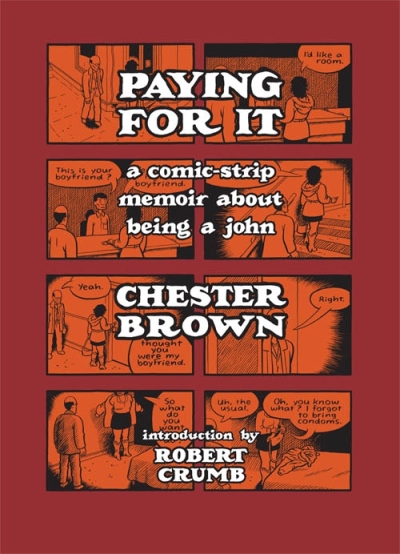

Paying For It is both autobiography and polemic. It’s autobiographical because it’s a blow by blow (no pun intended) recounting of a period in Chester Brown’s life when, after breaking up with his girlfriend, he starts to visit prostitutes. It’s also a polemic, defending his right to behave in this way, and an argument that prostitution should be decriminalised.

Paying For It is both autobiography and polemic. It’s autobiographical because it’s a blow by blow (no pun intended) recounting of a period in Chester Brown’s life when, after breaking up with his girlfriend, he starts to visit prostitutes. It’s also a polemic, defending his right to behave in this way, and an argument that prostitution should be decriminalised. One of its central tenets is that romantic love doesn’t really exist or, if it does, then that it’s an impractical way of forming a permanent relationship. As autobiography and comic, it’s brilliant. As a polemic, it’s seriously fucked up.

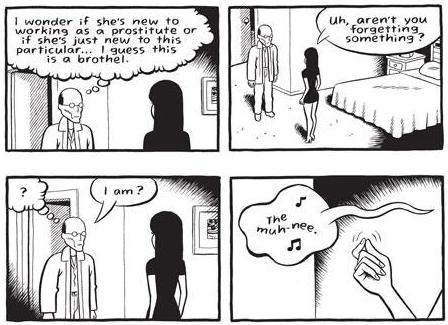

It’s structured in chapters with, after the first introductory chapters, each chapter recounting one of Chester’s visits to a number of different prostitutes. Some chapters are long, and some brief. Each one is unflinchingly honest, sometimes unflatteringly so as far as Chester’s concerned: he’s socially and emotionally awkward and, at times, paranoid. Premature ejaculation? Unintentional emotional cruelty to the women he visits? It’s detailed here. The prostitutes are never shown, their faces carefully averted and all drawn with uniformly long, black hair. This is to protect their identity but it can also be seen as a way of making them, literally, faceless. At the same time their bodies are carefully observed, as is Chester’s reactions to their bodies. Some of the encounters are amusing, some involving, some a little sad. One of the sources of humour in this comic lies in Chester Brown’s social ineptitude, and his careful chronicling of this trait. In that respect (and in a fearlessness of exposing this, and other peculiarities), he’s Robert Crumb’s obvious heir.

In between these encounters he records his friends’ reactions to his visits. These include his ex-girlfriend, Seth and Joe Matt. They provide arguments counter to his own, or are used as an opportunity to elaborate his own thoughts. Their reactions range from providing rationalisations for his behaviour, to curiosity, to, in Joe Matt’s case, jealousy because Chester is having sex, and he isn’t.

Throughout, as is common to all of Brown’s work, there’s the feeling that he’s indulging in a dialogue with himself as much as with his audience. The blunt detailing of emotion and scatological fascination shown here isn’t new, and can be traced back to the very first issues of Yummy Fur.

Throughout, as is common to all of Brown’s work, there’s the feeling that he’s indulging in a dialogue with himself as much as with his audience. The blunt detailing of emotion and scatological fascination shown here isn’t new, and can be traced back to the very first issues of Yummy Fur.

Throughout, virtually all the scenes are drawn in long to medium shot. There are very few close ups, and when there are, they focus on objects, or isolated parts of the body – envelopes full of money, hands, ears, a flaccid penis. Not once are we presented with a face in extreme close up. This is emotionally distancing (and emotional detachment is one of the book’s themes). I’m reminded too of an interview where, talking about his New Testament adaptations, Brown said he would make them even more distanced, even more minimal. This is exactly what he’s accomplished here. Virtually each page is divided in eight panels, so that it establishes a metronomic beat. The Harold Grey influence, so in evidence in Louis Riel, his last major work, has lessened, but here the art has been stripped down even further. It’s minimalist and uses repetition a great deal. At first glance this resembles the lazy sort of duplication seen in many newspaper strips – three or four identical panels, with the final panel modifying a gesture in order to deliver the punchline. In practice, the panels only appear to be identical. The focus pulls slightly in and out, at times it tilts slightly. This isn’t purely done for aesthetic purposes. It struck me that they’re composed and structured as if there’s always another, unseen, person watching. Who is this person – you, the reader? Or, bearing in mind the distanced nature of the perspectives, God?

Where all of the arguments come undone are in the comic’s final chapter, which throws an entirely different light on the events that have gone before. And then there are the huge, copious notes that make up the book’s appendix. Some of these make perfect sense (why shouldn’t prostitution be decriminalised?), some of it is naive (“she didn’t seem (as though she was a sex slave)…she was vey cheerful and attentive”) and some of it is quite bonkers (if legalised, prostitution shouldn’t be taxed because sex is sacred).

These notes read like self-justification and, on some level, I think Brown still feels judged by what’s he’s done, and is doing. That’s one of the things that make this such a rewarding and engrossing comic, quite apart from the voyeuristic appeal, and the technical brilliance. As a piece of work, it’s providing a more complex outlook than Brown can rationally provide, and this ambiguity is what provides the comic with its power. There’s been a lot of buzz about this book prior to its release, and deservedly so. In a year that’s seen some outstanding works released, this is up there with the best of them, and is likely to be seen as a landmark, pioneering comic in years to come.

Tags: Chester Brown, Drawn & Quarterly

This book sounds like it could be quite interesting, if a bit creepy. I have always got the idea that there is something a bit pondlife-esque about the clients of prostitutes, so getting some kind of insight into their thought processes. But still.

it’s very hard really to justify not showing the women’s faces – it’s not like anyone would ever be recognised from a Chester Brown illustration. It does sound like it serves to dehumanise the women in question, or that he is paying for sex with the same depersonalised woman in an endless series of different contexts.