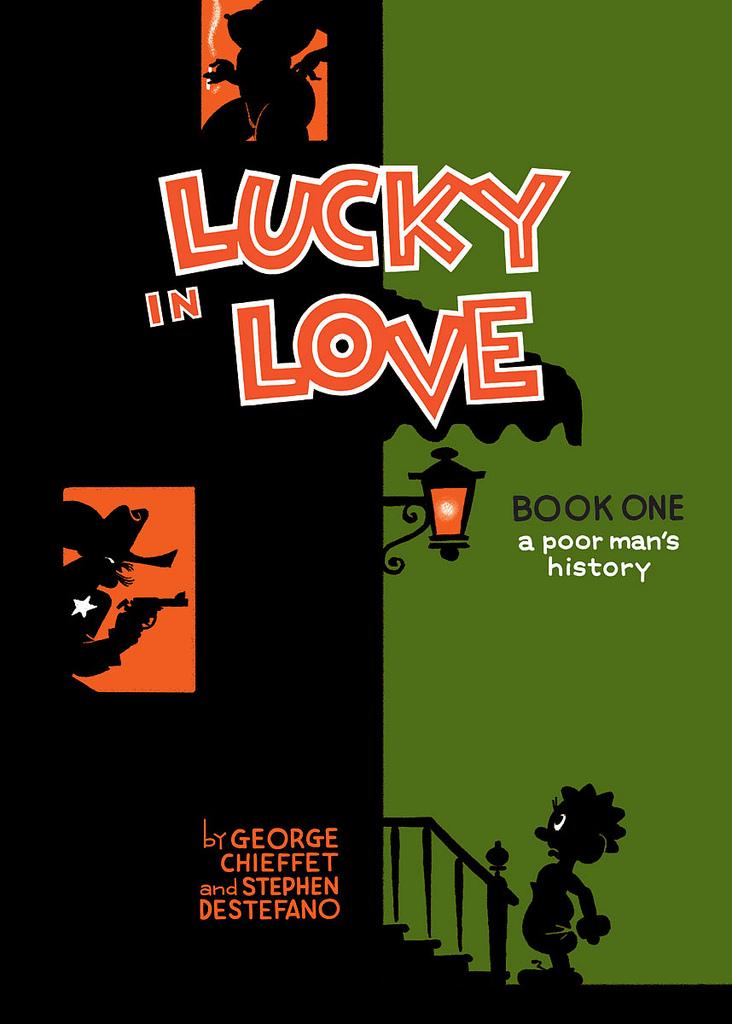

Lucky in Love: A Poor Man’s History

Reviewed by Jonathan Bogart 21-Dec-10

On the back cover of Lucky in Love, there’s a quote from David Mazzucchelli: “We’re all lucky when Stephen DeStefano draws comics.” Ignore the cutesy pun on the title, and there’s a lot of truth to that.

On the back cover of Lucky in Love, there’s a quote from David Mazzucchelli: “We’re all lucky when Stephen DeStefano draws comics.” Ignore the cutesy pun on the title, and there’s a lot of truth to that.

I first became aware of DeStefano’s work when, as an avid reader of anything DC Comics had ever published and an avid ignorer of everything else in comics, I fell in love with the gently parodic superhero series ’Mazing Man he had created in the late 80s with writer Bob Rozakis. ’Mazing Man was set in a colorfully ethnic New York neighborhood (well, Queens) and featured bits of random absurdism; for example, the benignly deranged lead character’s best friend (a writer for BC Comics; oh the satire) had the head of a dog.

DeStefano was at his best on ’Mazing Man when drawing absurdities like that, or the dumpy, terminally cute main figure; but when he tried to draw the semi-realistic supporting cast his art suffered, falling back on third-rate John Byrne imitations and the Nowhere Specific blandness of 80s commercial art. But that was all a long time ago.

Lucky in Love is the first half of a biography starring Lucky Testatuda, the son of Italian immigrants in a colorful New York neighborhood. (Well, Hoboken.) Like ’Mazing Man, Lucky is a comically short little guy with a rich fantasy life, at home in an absurd world. But poet and playwright George Chieffet is far more ambitious than DC company man Bob Rozakis was: he wants to evoke the texture of a lived – if not a particularly examined – life.

The love of the title is more or less ironic – Lucky cares about no one but himself, though he does have some sleepless nights over a WWII tragedy that may or may not have been his fault. What he is interested in, with all the enthusiasm of an ill-informed but necessarily swaggering young man, is sex. The biography doubles as a detailed, if at times willfully inaccurate, sexual history; Lucky tells it in the first person, and his captions don’t always match up with the action DeStefano portrays. The sequence where he (at long last) loses his virginity is an excellent example of comics’ ability to tell multiple versions of the same story, all at once.

But Chieffet, however ambitious he may be, is not the draw here. He falls prey to the usual temptations of writers new to the comics format: he overexplains, relies on words to convey ideas that would be better off left to the art, and spends pages infodumping so strongly that DeStefano has almost nothing to draw, breaking the illusion of time and place that the cartoonist has worked hard to create.

And few cartoonists are better natural time-and-place creators than Stephen DeStefano. His art has grown appealingly loose over the years, both paring down in affinity with the classic bigfoot style of Disney and Fleischer animation (at certain points his art looks almost like that of a sane Al Columbia) and growing more idiosyncratic, willing to take any shape or follow any pattern to serve the story. He uses many different techniques and explores different styles that students of classic cartooning can spend hours analyzing for fingerprints – off the top of my head, I recall references to the linework, shading, and gestures of Fontaine Fox, Bill Mauldin, George Baker, Harvey Kurtzman, Milt Caniff, Roy Crane, and Will Eisner, among many others. If the path to true originality, as endlessly reblogged Picasso quotes claim, is to steal shamelessly and widely, DeStefano is the most original cartoonist in a generation.

He’d be that anyway; while the story may not present anything very novel to anyone who’s spent much time in twentieth-century popular literature (though some of the details Chieffet either unearths or invents, like the greased-pole contest, do a lot to place Lucky in a specific historical and cultural context; I’m just dreading the inevitable Mafia references in the next volume), the reason this book cannot be missed by any serious fan of pure cartooning is DeStefano’s art, crisp black lines on creamy off-white, every stroke of the pen, brush, or pencil displaying the expert motion of the hand behind it. His work here repays close study on every level, from character design and background detail to page layout and the sequencing of action to the specific gestures and shading strategies he uses to convey specific emotions. It’s bravura cartooning at its best, and the world is better for Stephen DeStefano having an opportunity once more to show what he can do.

Tags: Fantagraphics, George Chieffet, Stephen DeStefano

Just read this book – was about to tell Martin I wanted to write a bit about this but thankfully saved myself some (considerable) embarrassment when I did a google search.

Your review is excellent. Every panel is a wonder of caricature, homage, and discipline – there’s a new thing to wonder at in every page. The cumulative effect of reading the book is astonishment at how thought through it all is, nothing slap dash – the placement of the pov, the size of the characters, the page layouts, et al.

Now I’ve got to hunt down some ‘MAZING MAN – darn!