Love From the Shadows

Reviewed by Peter Campbell 17-May-11

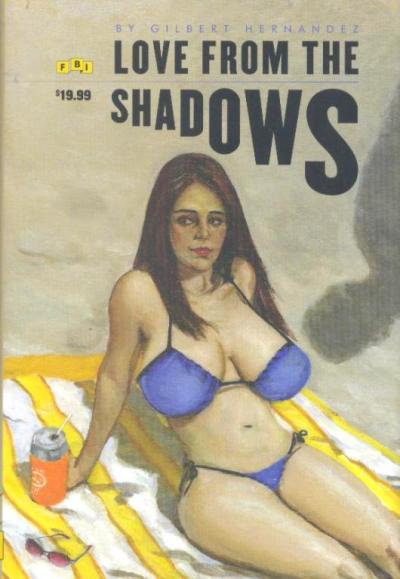

The painted cover of Love From the Shadows is deceiving, featuring as it does a rather anonymous looking woman half-lounging on a beach. Deceiving, because the woman bears little resemblance to any of the characters contained inside, and also because it’s painted by Steve Martinez, not Gilbert Hernandez. It has an old-fashioned, pulp paperback quality of the sort that promises the book contains a rather lurid and titillating storyline. Which indeed it does: but it’s also the most ambitious and successful of Gilbert Hernandez’ post-Palomar works to date.

The painted cover of Love From the Shadows is deceiving, featuring as it does a rather anonymous looking woman half-lounging on a beach. Deceiving, because the woman bears little resemblance to any of the characters contained inside, and also because it’s painted by Steve Martinez, not Gilbert Hernandez. It has an old-fashioned, pulp paperback quality of the sort that promises the book contains a rather lurid and titillating storyline. Which indeed it does: but it’s also the most ambitious and successful of Gilbert Hernandez’ post-Palomar works to date.

Backflip in time a bit. Love and Rockets had become, if hardly a household name, then at least a comic that had developed a loyal and enthusiastic following. There were signs though that both the Hernandez brothers were growing tired of the concept. Their work had lost some if its freshness, and the storylines tended to repeat themes and situations they had explored before. This was particularly evident in Gilbert’s work. Of the two brothers, his was the work that took the greatest risks, and you could see him trying to push against the boundaries that the Love and Rockets concept had imposed. When the series was formally declared defunct, his first release was the off-the-wall, though somewhat patchy, Fear of Comics.

I presume this and subsequent comics didn’t sell all that well because in time Love and Rockets was revived. This provided the brothers with same conundrum they had tried to escape from in the first place: attempting something fresh while meeting audience expectations.

Gilbert, at least, has hit upon a novel solution. By having his character Fritz star in a number of B movies, he’s able to produce a series of comics based on those movies. This gives him a commercial safety net (the L&R name, recognisable characters) while at the same time allowing him to develop standalone and often very experimental comics.

To date, these comics have been of variable quality, though they follow similar themes. They’re simultaneously trashy, lurid, surreal and profound. Often they feature scenes of extreme violence, disenfranchised characters who change roles and identities in an unsettling fashion. They’re absurd, melodramatic, and often ludicrously violent. This is the pattern that Love From the Shadows follows.

The storyline’s difficult to summarise, but the core concerns brother and sister, Dolores and Sonny, as they visit their estranged father, who is the author of best-selling horror novels. After he goes missing in a cave in the mountain, the events that follow lead to Dolores becoming involved with a team of quasi-spiritualist tricksters, and Sonny to plot inheriting his father’s money, events that lead to a violently bloody conclusion. In the background there are overtly surreal touches: the monitors, a cult that dress like refugees from a 1950s science fiction movie. Sonny becomes his sister, and then turns back to a man again. A ghost appears and delivers an obscure prophecy which Dolores aka Sonny fulfils, or possibly twists the prophecy to meet her/his own ends.

There are two influences that are strongly visible here, which are about as disparate as can be imagined. One is Dan DeCarlo. There are moments where the characters don’t simply resemble Betty and Veronica, they are Betty and Veronica, in all but name. Except they have ludicrously large breasts and indulge in activities that DeCarlo would never dream of committing to the printed page.

The other influence is David Lynch. The elliptical storylines, the identity shifts, the extreme acts of violence, they’re all recognisably Lynchian themes. Now, much as I love Lynch’s films, he’s not always the best role model. A bit like George Herriman, any attempts to replicate his work come across as a rather poor pastiche. It’s not so evident here, but in some of Gilbert’s comics, the appropriations from the likes of Mulholland Drive or Lost Highway are blatantly obvious. Here the Lynchian influence has been subsumed, and it’s all the better for it.

Throw into the mix too the fact that this is still a B movie that you’re reading, or a comic pretending to be a B movie. So Dolores indulges in graphic sex scenes (as does Sonny later, as Dolores), while Dolores spends a good half of the comic wandering around in a bikini, with no other justification that she feels like it.

This is drawn in Beto’s usual stripped down style. The DeCarlo influence I’ve already mentioned, but I see a bit of Steve Ditko in there as well, especially in the background elements. Crucially, as with his brother Jaime, he understands how powerful the use of black can be, illustrated in the Moebius strip opening and closing scenes with a figure disappearing into the depths of a cave. And as with all the great comics artists, there’s no elaborate displays of graphic prowess. The panels are uniformly rectangular, with the characters carefully placed to best emphasise the elements in the storyline that we, as readers, should be focussing on.

“How come you look like that? How come your skin is like that? How come you talk like that?” ask the monitors of one of the characters (who may or may not be Dolores) at the start of this comic. And that’s the crux of the entire storyline. It’s never clear quite who is who, or quite what is happening, but this is what makes this work so powerful.

A first reading of this comic is perplexing. A second and third reading draws its individual strands together, without offering up a concrete meaning. No, it’s not Human Diastrophism, but it doesn’t pretend to be. Consequently, it’s more likely to polarise opinion than Beto’s Palomar series. This is a strange, ludicrous, bewildering and remarkable comic from a creator working at the near peak of his powers, and I’m looking forward to subsequent volumes in the series hugely.

Tags: Fantagraphics, Gilbert Hernandez