Love and Rockets: New Stories 4

Reviewed by Tony Keen 12-Oct-11

Beto no longer achieves the same standards that he once set. Jaime, on the other hand, not only maintains his past standards, but is actually doing the best work of his career.

Gilbert (also known as Beto) and Jaime Hernandez have a good claim to be amongst the most important comics creators of the past thirty years. Their works were the comics Martin Skidmore could happily hand to anyone who didn’t read comics, and he began his Comics: A Beginner’s Guide series with them.

Gilbert (also known as Beto) and Jaime Hernandez have a good claim to be amongst the most important comics creators of the past thirty years. Their works were the comics Martin Skidmore could happily hand to anyone who didn’t read comics, and he began his Comics: A Beginner’s Guide series with them.

Like, I suspect, many Love and Rockets readers, I began by liking Jaime more. His Locas stories were fun, and his central characters Maggie and Hopey were delightfully attractive punkettes. Jaime’s was the cleaner artwork, he had the more obvious interest in superheroes. Beto’s work appeared cruder, more cartoony (not that Jaime can’t do cartoony when he wants to). But soon I began to appreciate the subtlety of Beto’s writing. His tales of the Mexican village Palomar displayed a subtle complexity, and an appreciation of magical realism, that truly made him the comics equivalent of Gabriel García Márquez. In Luba, the implausibly large-breasted giver of baths in Palomar, Beto created one of the most interesting and well-rounded characters of sequential art. And I learned to appreciate better the cleverness and skill of his art.

The first run of Love and Rockets ran from 1981 to 1996, was relaunched in a more traditional comics format in 2000, and was relaunched a third time as an annual trade paperback, Love and Rockets: New Stories, in 2008. But can the brothers still be producing high-quality work thirty years later?

In the case of Beto, the answer, at least in my view, appears to be no. The artwork is as good as ever, but the storytelling is far below par. In the mid-90s, Beto ran out of enthusiasm for the Palomar setting, and moved his stories to California, where Luba found long-lost half-sisters. But none of these characters had the depth of Palomar’s residents, and they never grabbed my interest.

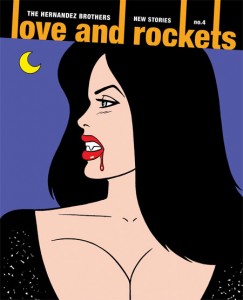

Now he has moved on to presenting stories that are intended as movies in which Luba’s half-sister Fritz has starred. His first story in Love and Rockets: New Stories 4, ‘King Vampire’ is one of these. Some people, such as Peter Campbell elsewhere in these pages, appreciate this approach. I’m afraid I don’t. ‘King Vampire’ is an incoherent story replete with nasty violence. It’s not that Beto’s work hasn’t included extreme violence in the past – the Godfather pastiche at the end of Poison River is particularly intense. But there it was offset with genuine heart, love and insight into the human condition. Here it’s just gratuitous. ‘King Vampire’ isn’t as nasty as Speak of the Devil, which caused me to take Beto-only works off my standing order. But that isn’t saying much. That this is supposed to be a Z-grade movie, and is supposed to be badly made and exploitative, excuses the incoherence and nastiness a little. But only a little. For all the meta-ness of the concept of making graphic versions of Fritz’s movies, the bottom line is that Beto has deliberately made a bad comics story. And what’s the point of that?

His other story here, ‘And Then The Reality Kicks In’, is a conversation between Fritz and what I assume is her lover. After fifteen pages, I was no wiser as to what the conversation was about, or why indeed I should care.

As for Jaime’s work … well, that’s quite another matter.

Jaime has not only managed to maintain the standard that he set in his Locas stories back in the 1980s and ’90s, but at times I would say his work is better than ever. I would argue that he has achieved this by having his characters age along with the readership. Such an approach isn’t common in comics – Spider-Man began as a high school student, but didn’t graduate from college until fifteen years later, whilst Charlie Brown barely aged a day in fifty years of Peanuts. But Jaime’s characters were in their late teens and early twenties when he first wrote about them, and they are now in their late forties and early fifties. The result is one of the most poignant and touching depictions I’ve ever seen of people who have aged without actually feeling they’ve grown up, and still feeling haunted by lost opportunities of their youth, i.e. many of the people I know (and, if I’m honest, myself). The development of the character of Ray Dominguez is central to this. Once merely one of Maggie’s lovers, Ray has developed into one of the central figures, the character whom one suspects Jaime identifies with most, displacing Hopey along the way. He is a relatively successful artist, and has access to nubile women twenty years his junior – but he remains hung up over Maggie, whom he clearly sees as the love of his life.

Jaime’s stories at the end of the second run of Love and Rockets were marvellous examples of this approach. I was a little disappointed, therefore, when the first two issues of Love and Rockets: New Stories featured a superhero fantasy that made use of some of the regular characters, but wasn’t part of the main narrative. It was perfectly all right, but it lacked the brilliance of the stories that had gone before. I needn’t have worried. In #3 he returned to the theme of his aging cast. #4 sees the end of ‘The Love Bunglers’, a story that is every bit as tragic, funny, and ultimately life-affirming as one could wish. In the incoherent words of Reno, Jaime sums up what his stories and his characters are about: “there’s somethin’ that happened once in our lives that keeps us … keeps us livin’, hopin’ that …”. The issue also includes a flashback to the 1970s, ‘Return For Me’, that ends with the sort of emotional shock that Beto once carried off when Tonantzin immolated herself at the end of Human Diastrophism.

The artwork is still marvellous. The clean lines and effective blacks, and Jaime’s story-telling skills, make the basic storyline easily followable without actually reading the word balloons. Even if you don’t know what Jaime’s characters are talking about, you know what they’re feeling, in a way that you don’t in Beto’s ‘And The Reality Kicks In’. And there’s one two-page wordless spread that is a beautiful piece of comics construction.

My only concern is that Jaime seems to have reached an end point with the story of Maggie and Ray. I’m not sure where he will go now – but I have enough confidence in his abilities to keep following.

I don’t want to completely reverse the judgement of history, and argue that Jaime was the best all along (though I think that praise of Beto over the years has obscured Jaime’s virtues). I still consider the Palomar stories up to and including Poison River to be among the finest work done in the medium, and would happily recommend them to anyone. But Beto no longer achieves the same standards that he once set. Jaime, on the other hand, not only maintains his past standards, but is actually doing the best work of his career.

Tags: Fantagraphics, Gilbert Hernandez, Hernandez Brothers, Jaime Hernandez, Love and Rockets

I agree that Jaime is still, incredibly, getting better, but you dismiss Beto’s work too easily. He’s always been the keener of the two to try something different, which has resulted in some poor comics in the past, but I really enjoyed his two stories in this latest book.

What about New Tales of Old Palomar from a few years ago? Surely as great as anything from the original run. I was bored with Poison River.

I confess to not having read New Tales of Old Palomar, and I’m not quite sure why I missed it.

But I stand by my judgement of stuff like Speak of the Devil or ‘King Vampire’. Yes, it’s something different, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s good. Speak of the Devil is a nasty and sadistic piece of work; ‘King Vampire’ is gratuitously violent and incoherent (an incoherence made worse by cramming what we are presumably meant to imagine as a seventy or eighty-minute movie into only thirty-odd pages of comics). Of course, one can deploy the argument of the metafictional concept: Of course the stories are nasty, incoherent and violent, they’re meant to be representations of movies that are nasty, incoherent and violent, and to criticise them on this basis is missing the point. Well, maybe. But I’m not inclined to give Hernandez a pass on this because of the metafictionality (or even just because he’s Gilbert Hernandez) – these stories seem to serve no purpose beyond themselves, there’s little evidence of parodic or satiric intent, and indeed Beto seems to revel in these stories. (I freely confess that part of the issue here is that Hernandez clearly has a nostalgic affection for terrible horror movies, and I don’t.) I come back to the point I made in the review – if one creates a metafictional version of what is meant to be a rubbish horror movie, one is deliberately writing a rubbish story. The question is, in the absence of trying to do anything more with the concept, is the metafictionality alone, or simply that it’s been done as a comic (or a comic by Gilbert Hernandez), enough to overcome the essential rubbishness of the story, or to justify repeatedly returning to the idea? Beto clearly thinks yes – I don’t agree.