Dredd

Reviewed by Gavin Burrows 20-Sep-12

The film’s an odd beast, often feeling like an exploitation thriller given a multi-million-dollar 3D treatment. Individual scenes are often strong in themselves, but they don’t necessarily add up to much.

By Pete Travis (director), Alex Garland (writer/producer), based on the comic strip by John Wagner and Carlos Ezquerra

By Pete Travis (director), Alex Garland (writer/producer), based on the comic strip by John Wagner and Carlos Ezquerra

Citizens! Some minor plot spoilers identified ahead! Advance at your own risk!

Sometimes failure can be the best thing to build on. This film’s predecessor, the 1995 effort Judge Dredd, was a masterclass in how to get a comics adaptation wrong – greedily grabbing at far too many original storylines in case it missed the right one, while failing to grasp the essence of its source. Once fans of the original 2000AD strip heard Dredd took his helmet off in it, it was already sentenced to the iso-cubes of their minds. Wikipedia dispassionately called the enterprise “a critical and commercial disappointment,” a verdict to which no-one had appended the tag “citation needed.”

Perhaps the twain were never likely to meet. As Phelim O’Neill commented in The Guardian, “The essence of Dredd is that he is almost an anti-character – he doesn’t change or learn.” Scarcely the stuff of Hollywood screenwriting classes, with their endless insistence on “journeys”, epiphanies and the like. But screenwriter Alex Garland had spoken from the get-go of something more loyal to the original strip, including a helmet that stayed firmly fixed on the lead character’s head.

He also smartly decided not to emulate any of the strip’s more epic adventures, but focus on a more straightforward and enclosed storyline. For the majority of the running time Dredd and Psi Judge Anderson are trapped in a tower block and forced to fight their way through the endless onslaughts of a murderous gang, a situation which develops in almost real time. He succeeds in establishing a kind of double vision, constantly ratcheting up the tension and jeopardy, while keeping you aware that for Dredd this is pretty much an average day.

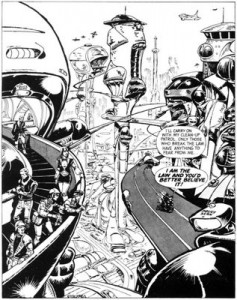

With a one-note lead, the focus in the strips was always either on Dredd’s more colourful enemies or on civilian characters. His dourly jutting chin made him the straight man to their increasingly deranged antics. The two artists who most defined the strip’s look were Carlos Ezquerra and Mike McMahon, cartoonists as much as they were adventure story artists. (Current 2000AD artist D’Israeli blogs about the strip’s original look here.)

With a one-note lead, the focus in the strips was always either on Dredd’s more colourful enemies or on civilian characters. His dourly jutting chin made him the straight man to their increasingly deranged antics. The two artists who most defined the strip’s look were Carlos Ezquerra and Mike McMahon, cartoonists as much as they were adventure story artists. (Current 2000AD artist D’Israeli blogs about the strip’s original look here.)

Story lines often embraced the bizarre or downright surreal. They were served up with black humour, and frequently tipped over into outright satire. (Dredd seemed to keep his helmet on even when relaxing at home.) And, of course, a satirical world must be cartooned, for it can never be quite credulous. It must always seem strange, for its purpose is to direct us back to re-imagine our own world, not suck us into another one. Hence Mega City One looked like another world, and not necessarily a sane one.

Judge Dredd started out with the black humour but couldn’t hold on to it, like a bad actor faking an accent. This time it’s woven into the film’s DNA. Dredd strides over to arrest a vagrant who he’d previously warned to “not be here.” A security door then happens to slam down, crushing the poor unfortunate. Noting the spreading pool of blood, Dredd immediately loses interest. Best of all, you’re never quite sure when he’s making laconic jokes or simply being himself. Two juves draw on him and shout “freeze!” “Why?” he asks, as if bemused by the order.

… but what’s missing is the strangeness and the satire. The violence is not cartoony but graphic, perhaps excessively so. Significantly, in the comic tower blocks were named after soap stars or bit-part actors, while in the film these become creators of the comics. But you note the absence most in the look of the film, which instead of a Seventies comic strip resembles Seventies cinema. It has the luridly gritty feel of cop or gang films of the era, such as Assault on Precinct 13 or The Warriors, filtered through the dystopian science fiction of Rollerball and Soylent Green. Picture a Seventies cop flick filmed on the set of Blade Runner, with extra side-orders of litter and graffiti. Dystopias assume the future will be like the present, only more so. And here Mega City One is New York, just bigger and badder. Even the 3D feels like a Seventies gimmick recycled.

… but what’s missing is the strangeness and the satire. The violence is not cartoony but graphic, perhaps excessively so. Significantly, in the comic tower blocks were named after soap stars or bit-part actors, while in the film these become creators of the comics. But you note the absence most in the look of the film, which instead of a Seventies comic strip resembles Seventies cinema. It has the luridly gritty feel of cop or gang films of the era, such as Assault on Precinct 13 or The Warriors, filtered through the dystopian science fiction of Rollerball and Soylent Green. Picture a Seventies cop flick filmed on the set of Blade Runner, with extra side-orders of litter and graffiti. Dystopias assume the future will be like the present, only more so. And here Mega City One is New York, just bigger and badder. Even the 3D feels like a Seventies gimmick recycled.

The clincher to this is the subplot with the turned Judges. One of the characters, Alvarez, comes from the corruption-centred comic story “The Pit”. But that came out in 1995, almost two decades into the strip’s history. More commonly rogue Judges would out-fascist Dredd, such as Judge Death, or be simply insane like Judge Cal. Corrupt cops were more a staple of Seventies cinema.

Neither is there the comic’s interest in other characters. Civilians are extras, to deliver plot information or get bumped off, one often following the other. True, the gang chief Ma-Ma is a potentially interesting character. She’s someone who refused to be a victim in a world where that inevitably meant becoming a perpertrator. (She deposes her predecessor by castrating him mid-blow-job, suggesting she has to “de-man” the man in order to take his place.) Yet her character feels underwritten. As she dispatches waves of minions, the whole film seems to build up to her final confrontation with Dredd and Anderson, then seems unsure what to do with it when it arrives.

Instead of perp or victim the film’s focus is on Anderson, the rookie out for her first mission under Dredd’s wing. If that’s a cliché it’s because it’s one which works – the audience-identification character thrown out of her depth, and gradually managing to swim. With the Judge/Perp/Victim triangle the film has set up, a rookie would seem the only break-point, the only way in for an audience. Moreover, she’s not just a sidekick – her psi abilities give her both an advantage and a dimension Dredd lacks, stopping the relationship becoming too one-sided. The problem is more that the spotlight which falls on her throws the other characters further into the shadows.

Instead of perp or victim the film’s focus is on Anderson, the rookie out for her first mission under Dredd’s wing. If that’s a cliché it’s because it’s one which works – the audience-identification character thrown out of her depth, and gradually managing to swim. With the Judge/Perp/Victim triangle the film has set up, a rookie would seem the only break-point, the only way in for an audience. Moreover, she’s not just a sidekick – her psi abilities give her both an advantage and a dimension Dredd lacks, stopping the relationship becoming too one-sided. The problem is more that the spotlight which falls on her throws the other characters further into the shadows.

If it doesn’t look or feel much like the comics, it should be said that taken on its own terms it looks and feels fantastic. Special credit should go to the sound design, the endless noises rattling around the block’s concrete caverns, often bursting into thundering gunfire, adding to the sense of place. It’s so much more effective than the musical soundtrack you find yourself wishing it could have been the soundtrack. (However, the two do have a neat trick of blending into one another.)

Despite the promises, despite even the promises it delivers on, the film works best when taken apart from the comic. Garland has spoken of this film as an introduction to the character, setting Dredd up to go against Judge Death. Yet it’s hard to imagine getting there from here, so strange and epic a story working within this style.

The film’s an odd beast, often feeling like an exploitation thriller given a multi-million-dollar 3D treatment. Individual scenes are often strong in themselves, but they don’t necessarily add up to much. Two of the most recurrent elements, the effects of the slo-mo drug and Anderson’s psi powers, bear at best a marginal role to the finale. It’s a bit like the film Dredd himself would write – “crimes committed, Judge negotiates obstacles, perp taken down, end of shift.” It may end up disappointing fans of the comics while not having a developed enough storyline to draw in more regular audiences. Which would be something of a shame. It’s far from a failure. But it’s differently successful.

Tags: 2000AD, Alex Garland, British Comics, Carlos Ezquerra, DNA Films, IM Global, John Wagner, Judge Dredd, Pete Travis, Reliance Big Pictures

For an interesting companion piece to this review, Pat Mills has posted a history of Judge Dredd’s creation, which he compares to the new film at a few points. The first part is here.