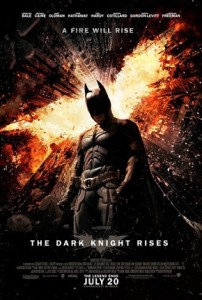

The Dark Knight Rises

Reviewed by Gavin Burrows 14-Aug-12

For those who favour soundbite explanations, this final part of Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy comes across as a mash-up of David Fincher’s Fight Club and Brecht’s anti-Nazi allegory The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui. (Contains spoilers.)

For those who favour soundbite explanations, this final part of Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy comes across as a mash-up of David Fincher’s Fight Club and Brecht’s anti-Nazi allegory The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui.

Just as the Joker dominated its predecessor, this film is filled by the new (to Nolan’s trilogy) villain Bane. And Bane’s similarity to Fight Club’s masculine destructive-id figure of Tyler Durden is first borne out by his appearance. His costume is mostly designed to throw emphasis on his imposing physique, forearms bared and face covered. Never did a supervillain look more like a pro wrestler. Unlike the elaborate death traps so beloved of the likes of Blofeld, he delights in dispatching foes and former henchmen with his bare hands.

A series of images show him inverting everything. His men start off hiding in the sewers, then manage to trap the cops down there just as they take over above ground.

Yet a weird double vision develops over Bane; he’s part gimp-masked bogeyman, whose aim is to terrorise, and part quasi-revolutionary insisting he’s come to liberate Gotham. In this way he’s like Brecht’s Hitler analogue Ui, spinning stirring speeches to the populace while rising to power on the backs of corporate barons. (Backs he summarily then breaks.)

The two collide in the stock market takeover. Like Fight Club‘s blue-collar guerilla army, it’s notably the manual workers (the janitor, the shoeshine boy, the truck driver) who rise up against their smart-suited masters. But of course they’re not real manual workers, that’s simply a disguise. In fact the film itself makes a motif out of no-one knowing where Bane gets his fanatical followers from. They’re that corporate media standby whenever trouble’s afoot, the “outside agitators”, the Mister Nobodies who are always the ones who turn up to cause mischief.

At points the film seems keen to riff on the emerging class dissent caused by the financial crisis. Bruce Wayne is flatly told at a society ball: “There’s a storm coming. You and your friends better batten down the hatches cause when it hits, you’re all going to wonder how you ever thought you could live so large, and leave so little for the rest of us.”

At points the film seems keen to riff on the emerging class dissent caused by the financial crisis. Bruce Wayne is flatly told at a society ball: “There’s a storm coming. You and your friends better batten down the hatches cause when it hits, you’re all going to wonder how you ever thought you could live so large, and leave so little for the rest of us.”

This has led some to claim Bane’s antics are a parodic critique of the Occupy movement. Which would seems far-fetched, even if it didn’t disregard the film’s lengthy production history. Nevertheless, there have been more nuanced critiques from a leftist perspective, such as Mark Fisher’s in The Guardian and Abigal Nussbaum’s. For example, Fisher comments “anti-capitalism is only allowed within limits… comment is fine, but any direct action against the rich, or revolutionary moves towards the redistribution of property, will lead to dystopian nightmare.”

Perhaps inevitably, then, some on the right have celebrated the film, such as Christian Toto’s review, “Batman Battles Bain, Nolan Nukes Occupy Wall Street”. Yet simultaneously others have seen in it a leftist plot! Rush Limbaugh, for example, has claimed Bane’s name to be a thinly veiled attack on Milt Romney’s venture capitalist outfit Bain. (Which would take some seeding, as the character first appeared in the comics in 1993.)

Meanwhile, Nolan himself has repeatedly insisted the film has no political agenda. (“We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks. We put a lot of interesting questions in the air, but that’s simply a backdrop for the story.”)

And perhaps there’s a way in which they’re all right. Nolan’s phrase “throwing things at a wall” is perhaps telling. In a method reminsicent of the recent reworking of Battlestar Galactica, the film is full of signifiers of and references to modern social concerns. The opening, for example, seems designed chiefly to evoke Abu Ghraib hoodings and the general war on terror. The film’s like a prism, reflecting our fears and concerns back to us, in a distorted and magnified form. Then, job done, it walks away. Some have their ideas validated through seeing them reinforced, others by fantasising they’re under attack. (By manipulating liberal elites or by American corporate propaganda, pick your fancy.)

But this is a superhero film. A big-budget, two-and-a-half-hour superhero film is still a superhero film.

Abigail Nussbaun correctly points out the “Great Man fetishism that has run through all of Nolan’s Batman films.” Yet this is a theme largely absent from his non-Batman work, raising the question of whether Nolan is arriving at the genre and finding the Great Man already present. The genre has its own momentum, its own gravity, its insistence on individualism, which makes it inherently difficult to capture social movements.

In a long section, Batman is thrown by Bane into a prison hole. The film scrupulously avoids even letting us guess where this might be, we’re just told it’s in the “ancient part of the world.” There the other prisoners are accoutrements, choruses and echoes, there to tell Batman things and react to what he’s doing. They work pretty much the way rich Westerners imagine foreigners will when encountered on their gap year, not living lives of their own but there to solemnly intone ancient wisdom and provide life-validation.

How do all those prisoners stay alive? Is there a hole canteen, kept just off screen? Do they club together and phone out for pizza? Maybe an underground allotment they all tend? Of course it doesn’t matter. It’s not a real place in any way whatsoever, even accounting for the fact it’s in a film. It’s a metaphor for Batman’s state of mind, a Bunyanesque pit of despair. It might as well all be taking place in his imagination. In fact, it quite possibly is.

Which is, you know, not a problem. Films have “off-map” places like that.

The problem is with Gotham. Because Gotham is no more a real place than that hole.

Mark Fisher pinpoints a curious absence: “the people have no agency in the film. Despite Gotham’s endemic poverty and homelessness, there is no organised action against capital until Bane arrives…”

Well, for that matter, even afterwards. The ball game scene is, in its way, just as telling as was the stock exchange. When Bane usurps the game and declares misrule, people are shocked and stunned. But they stay seated. In fact, from all else we see of them, they may remain stuck seated there for the rest of the film.

Some of Bane’s rhetoric suggests Brecht’s City of Mahagonny is being channelled alongside Ui, with Bane himself as the hurricane, intending to unleash unbridled licentiousness among the populace. In a parody of the French Revolution, he blows open the prisons. Yet there’s no indication of whether the people respond with fervour or fear. They’re simply absent, undelineated extras. The common herd get less of a look-in than they would in a Shakespeare play. (It’s perhaps reminscient of the way the ‘corner’ scenes were removed from the Watchmen film.)

Some of Bane’s rhetoric suggests Brecht’s City of Mahagonny is being channelled alongside Ui, with Bane himself as the hurricane, intending to unleash unbridled licentiousness among the populace. In a parody of the French Revolution, he blows open the prisons. Yet there’s no indication of whether the people respond with fervour or fear. They’re simply absent, undelineated extras. The common herd get less of a look-in than they would in a Shakespeare play. (It’s perhaps reminscient of the way the ‘corner’ scenes were removed from the Watchmen film.)

In fact the only representation we get of Gotham is a collection of (I kid not) poor li’l orphan boys, looking for substitute father figures to fly in and rescue them. (Not just that, but its also suggested the vulnerable’s best hope is that the rich get rich enough to feel like giving some money away to them. And not… you know… a redistributive taxation scheme, or anything foolish like that.)

Like the thin ice that Bane’s enemies are forced to cross, the film here hits a point where it daren’t go further. If the people of Gotham are mere prisoners and Bane a simple tyrant, we are somewhere we have been before. If Bane represents their worst instincts, as Batman does their best, things become more challenging. But if they succumb to those worst instincts, how can a superhero then fly in and make it all better just by hitting people? The film’s solution is to fill itself with elipses and evasions, avoiding certain questions as surely as a politician.

Hence, though it’s Bane who breaks Batman’s back in combat, his own back is broken more metaphorically – by conflicting demands thrown upon him. At times he seems intent on triggering some populist uprising. Yet at others he’s calling himself “Gotham’s reckoning, here to end the borrowed time you’ve all been living on”, as if all that rich vs. poor talk was just populist flim-flam.

As I’m always arguing, if you choose to cast the Devil in your films, you’re obliged to give him the best lines. But the film sets Bane up, then panics itself into undermining him. We’re told the Patriot… sorry, Dent Act has given Gotham safe streets, but nigh-on Martial Law. Except that’s the problem, we’re told that, in passing, by people of enough elevated status that none of it will affect them. Whereas we’re shown Bane busting the prisons open, with shots of some very stereotypical movie felons inside. What could give Bane’s acts a frightening measure of legitimacy is carefully neuteured. Yet if he isn’t some devilish tempter, leading flocks astray, if he’s just some wildcard upsetting people’s lives, doesn’t that make him just the Joker-lite?

But more importantly, if Bane’s goal is really to provoke unrest, to reduce us to our basest instincts, how does a time bomb help in all that? Bane publicly proclaims he’s handed the trigger to an ordinary citizen. But as Gordon later points out, the revolution is in no way genuine, so of course he hasn’t kept to this promise. And he hasn’t.

When he takes over, Gotham falls into Winter. Perhaps this is partly to demonstrate the passage of time, that his rule lasts many months. Yet that explanation feels ostensible. The real reason is to tip us off that the wicked witch has arrived, and brought with her the Narnian winter.

After Dark Knight, I commented on how the figure of the Joker dominates the film by undermining it: “The whole structure can’t withstand the presence the Demon Clown it itself releases, he corrodes what it is trying to create.”

Conversely, Bane has succeeded only in controlling Gotham, which exists in the film only as a token for him and Batman to fight over. It’s much like the pearls Selina Kyle snatches, just bigger. Bane talks the talk of a larger and more powerful figure, the ancient Lord of Misrule (“as I terrorize Gotham, I will feed its people hope to poison their souls”). But he soon falls back into the standard supervillain role.

Similarly Batman’s assertion “A hero can be anyone”, that anyone can don a mask, that a superhero is an emblem of something not someone, is undermined by the Great Man role the film thrusts upon him. All this talk of Gotham needing Batman is like the myth of the King serving his people, poeticised bullshit to disguise a relationship ordered quite the other way around. His story arc is based around the concept that a King’s role is a calling, which he’s unable to escape. (Without Batman, Wayne essentially has the un-life of a recluse.) A King symbolically serves his people and so must be willing to die for them. Except of course that’s not what happens. Everything else is strung around the story of how Bats got back his mojo, even the many deaths and months-long servitude of thousands of people.

Like Dark Knight, this film is a three-hander. Formally, Bane takes up the Joker’s role as the antagonist. But it’s Selina Kyle (Catwoman, though never named as such) who takes over his actual disruptive function in the film.

Like Dark Knight, this film is a three-hander. Formally, Bane takes up the Joker’s role as the antagonist. But it’s Selina Kyle (Catwoman, though never named as such) who takes over his actual disruptive function in the film.

First seen purloining from Bruce Wayne’s safe, her servant disguise makes her almost akin to Bane’s henchmen. Yet there’s also her sole trader status, her fleet-footednesss, the fact that this is Wayne’s safe… she cheerily challenges his simple dichotomies. After all, it’s easy to criticise “crime” when you’re living in a mansion and not really wanting for much.

She’s a very modern genre movie girl, poised somewhere between the Black Widow in The Avengers and River Song in Doctor Who. River Song is of course all about upending the title character’s world. Plus there’s a very similar scene in Dark Knight Rises to the Black Widow’s introduction in The Avengers, aimed at inverting the damsel-in-distress stereotype.

Needless to say, Selina eventually succumbs to Batman’s protective arms and moral compass. Like the Black Widow, like River Song, she’s just bad enough to get sexy for the boys without scaring them off. It’s all rather reminiscent of the lyric from Lana Del Ray’s recent hit ‘”Video Games”: “Tell me all the things you want to do/I heard that you like the bad girls/Honey, is that true?”

Yet at the time time it’s perhaps too easy to play up this “love interest” aspect of her. Unsurprisingly, running around in her skintight latex, she’s a boy’s fantasy. But her appeal lies as much in wanting to be like her as much as wanting to tame her; she’s simultaneously pin-up girl and role model. While heavy hangs the cowl over those Bat-ears, she spends most of her time grinning like the cat who got the pearls. She’s wild, and lives by her own rules while all about her are feigning to live by saluting lies and holding to fake strictures.

As well as the above she’s similar to another audience-favourite character, Omar from The Wire, and his code of only robbing from criminals. (These new style Robin Hoods do tend to rob from the rich and keep it all themselves.) It’s possibly significant that Omar is one of the few characters in The Wire to be gay, as popular culture often assigns similar functions to gay men as to women. Being outside the dominant, hetero male society, it’s easier for them to represent a critique and even an inversion of it. Yet, despite his popularity, Omar was used sparingly in The Wire; he needed those other (in about every sense of the word) straighter characters to spark off in order to function. Whether Selina Kyle would work as effectively in the mooted solo Selina film remains to be seen.

In general Selina seems the character audiences warm to, and then debate whether she saves the film or just provides a redeeming feature. But in the most generous reading of her, it could be argued she epitomises the whole film, provides a means to see it from the correct angle. Okay, it’s unfocused, sprawling and ultimately incoherent. But perhaps a review of a film is inherently some kind of mismatch. There’s no point to looking at a collage and saying it’s not much of a painting. A film which is less interested in working like a balanced and well-argued essay than in throwing crazy notions out at the audience for them to deal with… there is something to that idea, even if it doesn’t work it’s best here.

There’s now been a series of superhero films which have spent their first instalment assembling themselves, swung into action with the second then in their third taking the first in reverse – what had seemed to bolt together starts breaking apart again. Spider-Man 3, for example, seemed to contain all the characters, plot elements and themes who hadn’t made it into the first two, which then hung about making awkward conversation. The Dark Knight Rises isn’t really much of an exception. It’s like that cookery show where chefs have to come up with something from an incongruous set of ingredients. If it has its moments then that’s because it’s only moments.

Tags: Batman, Christopher Nolan, Dark Knight Rises, David S. Goyer, DC, DC Comics, Jonathan Nolan, Warner