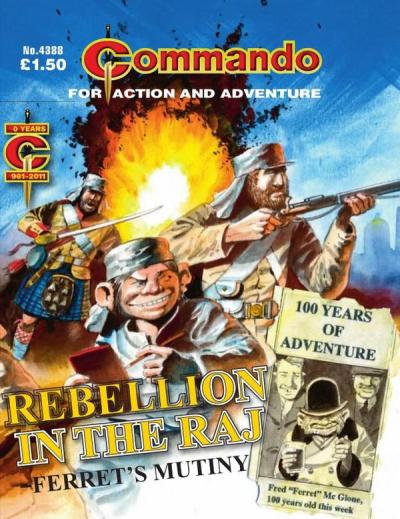

Commando 4388

Reviewed by Ian Moore 13-May-11

Commando is a British comics institution. The title has been appearing continuously since the early 1960s and is one of the last of the old-school British comics. Each diminutive issue presents the reader with a self-contained war story, usually set in the Second World War. The book typically presents a rather unreconstructed version of military events, with the British and their allies as the good guys and the Germans, Japanese and so on as sinister villains.

Commando is a British comics institution. The title has been appearing continuously since the early 1960s and is one of the last of the old-school British comics. Each diminutive issue presents the reader with a self-contained war story, usually set in the Second World War. The book typically presents a rather unreconstructed version of military events, with the British and their allies as the good guys and the Germans, Japanese and so on as sinister villains. The warfare depicted is usually rather anodyne, with a noticeable lack of gore or slow, lingering death. Bullets deal out a quick end, barely leaving people enough time to say “Aaarrgh!”, if they are German, or “Aieeee!”, if Japanese (or Jap, as Commando episodes still refer to people from Japan).

This particularly episode is unusual in that it eschews the Second World War in favour of a story set during the 1857 Indian Mutiny against the British East India Company, although it features a framing device set in 1945 on the day of the Japanese surrender. An old war correspondent (whose other adventures may have appeared in previous Commando issues) is reminiscing about his beginnings in the journalism trade, when an unlikely sequence of events found him out in India covering the struggle against the Indian rebels. He finds himself witnessing the siege and then relief of Lucknow, one of the great victories of British arms in that conflict.

The narrative jogs along, with event following event and strange reversals striking the journalist and the other characters. The art brings me back to the glory days of British comics publishing, at times calling to mind the old humour titles as well as the largely vanished adventure and war comics. It also serves up the faithfulness to uniforms and military equipment for which Commando is famed. But there is still a certain emptiness to it all. Moving from the moral certainties of the Second World War should give the story a chance to engage with the moral ambiguities of the colonial era, but instead ‘Rebellion in the Raj’ gives us a simplistic narrative in which the Indian rebels are all fanatics. There is no sense of their being in any way motivated by a desire to throw off the shackles of a rapacious imperialist enterprise. And the British are represented a bit too squeaky clean – although we do see soldiers looting after the Indian rebels have been defeated, there is no depiction of the indiscriminate bloodbath followed the defeat of the real rebels.

Maybe it is expecting too much for a comic like this to attempt a nuanced analysis of the British colonial project in India. But still it seems a bit much to set a story in such a complex period and then present it as a simplistic tale of good British against bad Indians.

One thing I am curious about is who reads Commando. In the old days, it was read by boys for whom its Second World War stories were still glamorous and exciting, with many of its readers having fathers or other relatives who had taken part in that conflict. I suspect that now it has a readership of adult war enthusiasts who like the images of carefully rendered kit and who get a nostalgic thrill from the Manichean narratives of the Second World War. It is unfortunate that such people would be satisfied with the simplistic and ill-considered analysis of the Indian Mutiny presented in this particular issue, but then there is no accounting for taste. On the other hand, if Commando is still primarily being read by children then I find it even more disturbing that such a whitewashed version of colonial history is still being peddled to unformed minds.

Tags: Commando, DC Thompson, Keith Page, Norman Adams

Is that Alfred E. Neuman on the cover?

he does have rather unrealistic features – compared to the more usual pictorial realism featured in Commando. But he is actually a journalist nicknamed The Ferret.

because I am a bit slow, I have only just noticed something really obvious about Commando – they are incredibly texty, with intrusive narration that explains everything, almost like the writer does not trust the artist to depict what is happening, or the writer is unable to conceive of a combination of illustration and dialogue conveying enough information to the reader. I reckon they are so texty that you could probably follow the story just from narration and dialogue, even if the pictures were erased.