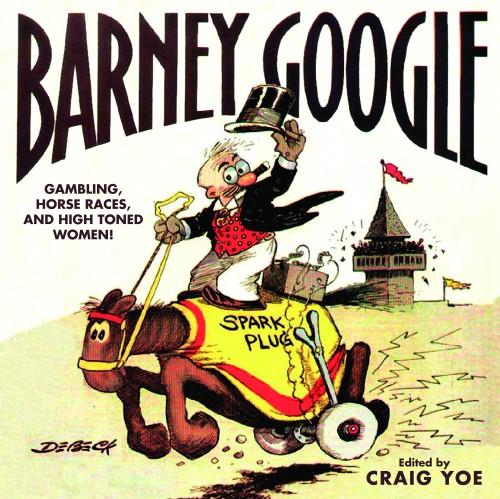

Barney Google: Gambling, Horse Races, and High-Toned Women!

Reviewed by Jonathan Bogart 12-Nov-10

Barney Google was the great picaresque comic strip of the 1920s and 30s. Billy DeBeck’s artwork, more notable for its energy more than for its draftsmanship, was unique on the comics page, a scribbly, gestural line supported by shrewd shading and opulent backgrounds that were more suggested than drawn.

We are living, as many people have noticed before now, in a Golden Age of comic-strip reprints: fat volumes full of ancient scribbling and revelatory scholarship about the scribbling appear with such appalling regularity on the shelves of my local comics shops (which don’t even particularly cater to that crowd) that I’ve started to have to ask myself not whether I can seriously afford to buy everything I want (the answer is obviously not), but whether I will feasibly be able to read it all within the span of years left me. The major canonical strips — Krazy Kat, Peanuts, Prince Valiant, Pogo — are either well under way or about to be so. The classic adventure strips — Thimble Theatre, Terry & The Pirates, Dick Tracy, Little Orphan Annie, Captain Easy — have reached the point of self-justifying returns. And the minor treasures, singular visions on a smaller scale — Gasoline Alley, King Aroo, The Moomins, Polly & Her Pals — are being issued as labors of love to the rapturous affection of dozens, if not hundreds. Hell, even the syndicates have started to take notice that their back catalogue is worth something: The Family Circus, Beetle Bailey, and Blondie — surely the three strips least necessary to be completist about — all have first volumes and threaten more.

All of which is by way of establishing the world into which this volume is quietly, not to say unceremoniously, thrust out onto shelves, and we are left to make of it what we will.

Barney Google was the great picaresque comic strip of the 1920s and 30s. (In the 40s he met Snuffy Smith and the feature dwindled to its current status as an occasional subject of the Comics Curmudgeon’s mockery.) Billy DeBeck’s artwork, more notable for its energy more than for its draftsmanship, was unique on the comics page, a scribbly, gestural line supported by shrewd shading and opulent backgrounds that were more suggested than drawn. (Again, once the Depression was over his line scrubbed itself off and his style became standard bigfoot cartooning, Walker-Browne with dumpier proportions.) It began as a standard henpecked-husband feature in 1919, perhaps slightly more witty in its misogyny than the standard: women on the comics page were nearly universally either shrews or temptresses in the teens.

This volume picks up, with no reason given, in March of 1922, and fizzles out early in 1923, although if you’re familiar with the history of the strip you can deduce that it’s because 1922 is the year that DeBeck quietly dropped Barney’s wife from the strip, gave him a racehorse named Spark Plug (only rarely seen without the shapeless blanket which is his visual trademark), and set his hero chasing after money, women, and (occasionally) doing the square thing. Craig Yoe’s introduction, while full of neat memorabilia (shown off in self-consciously wacky page designs) is far more interested in DeBeck’s raucous personal life than in the strip; as a comics “scholar,” Yoe is best known for poorly-designed, vaguely-sourced volumes of good-girl art, a jokey we’re-all-guys-here tone, and heaping scorn on the notion of serious, artistically challenging comics. The subtitle to this volume is representative: Yoe isn’t interested in digging below the surface of Barney’s raucous hijinks — if the strip is misogynist, it’s news to Yoe, as the existence of any misogyny would presumably be — to examine the social, political, or cultural milieu in which DeBeck was working. (The standard disclaimer about the strip’s racial attitudes aside.) DeBeck was a cartoonist who drank, flirted and gambled, and that’s good enough for him.

But intellectual incuriosity and an off-putting personality in editors can be put up with for the sake of the work; Yoe’s real crimes here are in design. DeBeck was not yet at the height of his powers as a cartoonist: in 1922, his line was still much more scribbly than gestural, and none of these strips are graphically interesting enough to take up an entire page. Yet that’s the choice Yoe made: rather than presenting the strips horizontally (as they originally ran), and two-to-a-page (as has become standard in reissues), he’s tiered them and blown them up unnecessarily huge, wasting space that could have been put to presenting a year or more worth of strips. Nowhere on the cover, the indicia, or the introduction do the words “Volume One” appear, and no doubt for good reason: at $40 a pop, this collection demands a substantial investment for very little return — a year’s worth of strips, no more — and even as a devoted fan of Barney Google (it’s one of my two or three personal favorite strips) I can’t imagine wanting to digest him in these unappealing slabs.

Hopefully someone will eventually do right by DeBeck; in the meantime, these early strips are interesting, but rarely more. Like most great comic strips, it took a while to get great; if all I had to go by was the evidence here, I might think that the strip deserved its Comics Curmudgeon fate.

Tags: Barney Google, Billy DeBeck, IDW, newspaper strips

“a racehorse named Spark Plug (only rarely seen without the shapeless blanket which is his visual trademark)”

Only going by the cover illo above but… a kind of riff on the Yellow Kid?

Not really, because the text never changes, and in fact there usually isn’t any. I think DeBeck just found it easier to draw a shapeless blanket than even the cartoon anatomy of a horse. It’s definitely funnier.

I did not realise that the name Barney Google pre-existed the lamer pub here in Dublin.

What template do you use in your blog