Ayako

Reviewed by Martin Skidmore 08-Dec-10

In my mind, a big new (well, new in English – this is from 1973) Tezuka graphic novel is a major comics publishing event. I don’t think I’ve been as excited about reading a new comic in many months.

In my mind, a big new (well, new in English – this is from 1973) Tezuka graphic novel is a major comics publishing event. I don’t think I’ve been as excited about reading a new comic in many months. I was a bit surprised that my regular shop hadn’t put it in with my comics, since I buy everything by him, so I asked. The assistant, a knowledgeable woman who writes the shop’s blog, didn’t know there was a new Tezuka. It’s probably downstairs, she told me, and I had to walk back down there and ask. They’re one of the most enlightened comic shops about things beyond the supermainstream, too. Clearly this isn’t a major publishing event for so many others, which makes me sad.

I think we are starting to take Tezuka for granted these days, in a way that wasn’t possible when I first wrote about him back in the old print FA over 20 years ago. There are around 70 volumes of his work translated now (which is still mot much more than one tenth of the total), from Astro Boy collections to hefty tomes like this one; and I think his central place in manga, as Japan’s God of comics, means that to a generation very familiar with manga styles, he of course looks entirely mainstream, stylistically right at the heart of the most common appearance, because simply everyone in manga learned from him more than anyone else. No other country had a figure so crucial in the form – even someone like Kirby simply doesn’t compare in influence. I think it’s all too easy to just say yeah, he’s great, and move on. His total mastery, the apparently casual ease with which his pages are created, is both true and deceptive. He (with his studio) was producing 300 pages a month right up to his death, and we are all conditioned to regard this as a sign of hackery; the notion of the tortured artist taking pains over every scrap of work has a powerful hold in the West, and the heavy influence of auteur theory has made us sceptical of great creators with a squadron of assistants. For the record, it’s said that at the least he wrote just about everything, laid out just about every page, pencilled main figures, and inked the main characters’ faces (and more on the more personal works, which this would be): this is still auteur-like control of the finished work, for me (leaving aside for now questions of whether auteurist ideas need to be applied quite so wantonly as they are).

Speed in art is a different thing in Japan. Great Zen painters might take half an hour creating a painting, not weeks or months. Probably Japan’s greatest ever sculptor, Enku, made a youthful vow to create 120,000 devotional statues in his life – no one knows if he made it, but those found strongly suggest that he got close, at least. For me, the most exciting contemporary Japanese movie director is Takashi Miike, who has frequently made half a dozen movies in a year. There is simply not a perceived connection between slowness and quality.

I think also that we mistake a cartoony style to mean a less than serious approach, probably because of the old notion that striving for representational realism is the height of greateness in art. Again, this attitude and tendency simply never existed in Japan – the great Zen painters produced human images every bit as cartoony as Tezuka’s manga. As it happens, this is one of the very rare Tezuka works which doesn’t deliberately undercut what serious and realistic atmosphere he creates with extremely exaggerated cartoon moments and antirealist panels: the mood here is consistent and very naturalistic, and he leaves out his troupe of stock actors, giving us a new set of faces.

But let’s get back to that total mastery, to a degree that I think has rarely been approached in the world of comics: even my current favourite comic creator, Ai Yazawa, has shown her extraordinary mastery only in a narrow range of subjects or genres. Tezuka seemed completely comfortable with short stories, series of shorts, sequences of graphic novels, and big standalone stories like this one. He could do realism, adventure, comedy, thriller, horror and SF, and even the fantasy cum religious biography of the Buddha series. He was an extraordinary writer in absolutely any of those modes, whatever the degree of seriousness or the genre, his work crafted with colossal skill and profoundly infused with his regular humanist concerns and sensibilities. As a storyteller, a layout artist, he is arguably the best ever, not just for the seemingly easy and flawless way he tells the story in the pictures, but for an often unappreciated degree of formal inventiveness – his panel layouts are immensely imaginative, not like those of any predecessor, and few since have learnt enough from him in this line (Yazawa is the shining example of someone who is perhaps even more imaginative). Few artists have been able to work with such a range of faces, animating each with strong and complex feelings. He composed glorious panels too – page 85, a full-page panel of a man basically begging forgiveness to the heavens for what he is about to do, a small figure on some railroad tracks with just rain filling almost the whole page, is absolutely stunning, a major showstopping moment.

Hm, I should get back to this comic, rather than just talking generally about how magnificent Tezuka was. This is a 700-page tale of post-War Japan, starting in 1949 with a young soldier, Jiro, finally returning to his family. Some of whom are monstrous: it soon becomes clear that the father of the daughter of Jiro’s big brother and his wife is in fact Jiro’s father, and the brother gives his wife to his elderly father in exchange for being the heir to everything. The tensions are immense. Our protagonist also has a dark past – we get early hints of terrible behaviour in the POW camp he’d been in, torturing him, and he has a shady role, rather secret agentish in nature, with some sort of agency.

That mastery I keep talking about: take a look at the wordless seven pages starting from page 96. The shapes and sizes of the panels varies enormously, and it’s an absolute masterclass in control and timing. Page 100 in particular is a gem that crystallised what it was reminding me of: the breathtaking long wordless opening scene of Leone’s Once Upon A Time In The West – the dropped cigarette here is an absolute masterstroke.

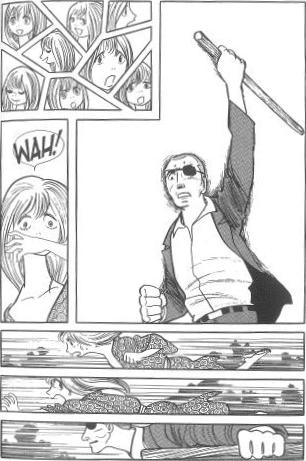

Or look at page 125 (pictured) – I’ve never seen a segment of a page like the upper left eighth, with its eight jagged panels as a girl realises and reacts to an unexpected threat, and the sense of pace in the bottom third where she flees from him, with three full-width panels, eight times as wide as high, is also unmatched in my experience. In between, note that the threatening male is inked differently from any other panel in the book, giving an astonishingly powerful impact. This is great and untrammelled comics storytelling, an artist devising three genuinely original techniques in a single page, to tell his story with the maximum possible effect. This is more than most come up with in their whole careers, but it was more or less routine for Tezuka.

Or look at page 125 (pictured) – I’ve never seen a segment of a page like the upper left eighth, with its eight jagged panels as a girl realises and reacts to an unexpected threat, and the sense of pace in the bottom third where she flees from him, with three full-width panels, eight times as wide as high, is also unmatched in my experience. In between, note that the threatening male is inked differently from any other panel in the book, giving an astonishingly powerful impact. This is great and untrammelled comics storytelling, an artist devising three genuinely original techniques in a single page, to tell his story with the maximum possible effect. This is more than most come up with in their whole careers, but it was more or less routine for Tezuka.

The story revolves around an extraordinary event. Jiro’s 4 year old sister, the Ayako of the title, is witness to something that could bring down the family, and you clearly can’t rely on a child to keep secrets. They collectively decide to pretend she has died and to lock her away in a basement. She is contained there for something like 22 years, through which the story moves at some pace, resuming in 1972 when road building forces her removal.

Tezuka is the most humanist of writers, someone with profound concerns for the best qualities of people, but here he has given us a family of monsters. Unusually for him, he also explicitly links this to larger social and political matters, in particular the US’s influence on Japan in the post-War years, and political corruption. In this context, shutting away the one witness to the evil of the family for decades is a clear parallel to the country turning a blind eye to what went on in the country. Tezuka is too complex and substantial a writer to make this into a mere allegory, or to become too literal or mechanical in his metaphor, so Ayako becomes the major character of the story, and a significant driver in the horrible climax and resolution.

I think this is a contender for his best single work so far translated, but I am conscious that that body of work is a small fraction of the total. I really hope books like this can sell enough that they keep coming, preferably at an increasing rate, if we are to see it all in English before I die.

Tags: Manga, Osamu Tezuka, Vertical