Dan Abnett

by Lee Harris 28-Nov-10

Dan Abnett has been writing comics for 25 years, and is best known of late for work on Marvel’s cosmic heroes, including the Nova and Guardians of the Galaxy titles.

[The interview as conducted at the British Science Fiction Association meeting in August 2010 ranges across Dan’s dozens of novels and his recent screenplay work (Ultramarines, a Warhammer 40000 animated movie due for release tomorrow) as well as comics. For FA we are extracting the comics material only. Thanks to interviewer Lee Harris, organizer Tony Keen and of course Dan Abnett for permission to print this. – Martin Skidmore]

Dan Abnett (talking about writing tie-in and licensed properties): I remember when I was writing juniour comics based on the character Batman, the Batman character bible ran to about nine pages. They distilled sixty years of continuity down into nine pages, but they were the basic things you needed to know about Bruce Wayne and Batman: these are the marks you must hit, these are the things you must not do with this character. Fairly straightforward and fairly representative of the usual sort of guidelines you get. For my sins, for a while I wrote the Happy Meal comic for McDonalds, and the bible for Ronald McDonald was I think 37 pages. So there was more guidance for Ronald McDonald than there was for Batman. It was scary. It wasn’t even that there was some untold origin there that I could tap into that hadn’t been published, it was all stuff about what he would do and what he wouldn’t do and things you were allowed to show him doing and things you weren’t allowed to show him doing. So sometimes there can be unnecessarily cumbersome things. Never write a McDonalds comic, is my answer for that.

(Addressing a question about how he got started writing Warhammer books for Black Library) I grew up as a cliché. When I was about three or four years old I developed Perthes’ disease in my left hip and I had to wear calipers, you know those metal frame things, so I didn’t get to do all those things like ride a bike and all the other things that you do in that period. I read a lot, and developed a great enthusiasm for writing and drawing stories and for years I thought I’d go to art school and become an artist or an art teacher or something like that, and I used to draw my own comics, because it was a wonderful way of telling stories and drawing pictures at the same time, it was an obvious hobby for me. I ended up, I stopped drawing my own comics because I couldn’t draw them fast enough to tell the stories I wanted to tell, so I ended up just writing. I did a degree, and I ended up at Marvel because I had this interest in comics. I sort of landed on it by accident. I applied for a job when they were advertising a job and I didn’t know they were advertising a job and they thought I was applying for it and it was the strangest interview ever, and I ended up as an editorial assistant. The financial remuneration at Marvel was not great in those days, and there was no such thing as overtime, so what everybody did was they freelanced colouring or lettering or any of the ancillary tasks, they would take them home. One of the things you could do was write stories. Editors were encouraged to do so because it was a way of showing that we understood story structure so we could then commission stories from other people. I think my very first piece of professional writing was Action Force, which was the British GI Joe, drawn by Bryan Hitch, who then was a completely unheard of young lad, and then I found my way into writing for Transformers, Care Bears, Thundercats, Transformers, and most particularly Ghostbusters. I was for 173 issues Egon Spengler and I wrote the Spengler’s Spirit Guide, which is where I honed my skills for making up absolute bollocks – that was the cornerstone of that column. That was my overtime, as it were, and it was something I enjoyed enormously. Upstairs in the grown-up part of Marvel was Doctor Who Magazine, and when I’d written the umpteenth Ghostbusters somebody said to me “They want you to write a Doctor Who strip for Doctor Who Magazine, which John Ridgway would draw.” That was like the most incredibly serious thing I’d ever done, it was like being promoted to the premier division, and I remember freezing up completely because I was absolutely convinced that everything I had ever written before then had been based on an old Doctor Who story, and I had no grounding on which to base a story for Doctor Who because people would obviously notice. I wrote comics, I realized I liked writing comics more than anything, quit the day job, became a freelancer, wrote comics for eight or nine years, and I was a comic book writer when Black Library approached me, and they said originally, “We are thinking of publishing comics based on Warhammer and Warhammer 40000, we hear you can write comics.” I’d been recommended because I’d just written a couple of Conans for Marvel, and they said “We think you’re the man for us.” Luckily, although I hadn’t played it, I knew what Warhammer and Warhammer 40000 were because in my youth I was a keen role playing gamer and was familiar with White Dwarf and was familiar with the things that had grown into Warhammer and Warhammer 40000. I had to follow the rules, but I got it quite quickly.

Lee Harris: You’ve worked for 2000AD, for DC, a lot these days for Marvel. Is there much difference in the writing process? Creatively do they give you more or less freedom? How is it working with the different companies?

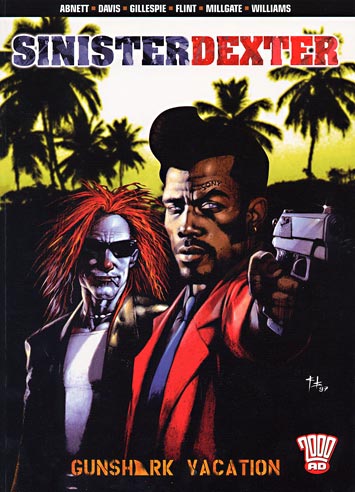

DA: There is an awful lot of difference depending on the property you are working on. For instance, 2000AD, I’ve been working for them for about 15 years. I’ve written Judge Dredd, I’ve written characters created by other people. I’ve also created my own characters, most particularly Sinister Dexter and the series Kingdom, things like that, where I set my own ground rules, built my own worlds and have written them successfully ever since. So there is a great freedom there, whereas for Marvel or DC there is this enormous weight of continuity when you pick up a character, you have to go through approvals, you have to make sure you are handling them correctly, which however can be enormously pleasing because I’ve loved Marvel comics particularly, and it is a sheer delight to actually be able to write some of those characters, it’s getting to write something that I’ve wanted to do all my life. Obviously there are other differences, like a Marvel or DC title is a 22 page monthly installment, it’s not just longer because there are 22 pages of it, the whole structure of doing it is different. 2000AD tends to be five or six page weekly installments, so you’re writing a story with a completely different narrative structure, a very different dynamic. There’s a very British feel to 2000AD, which means you can write the kind of stories that no American publisher would necessarily accept – and vice versa: the stories I write for Marvel would not be 2000AD fare at all.

DA: There is an awful lot of difference depending on the property you are working on. For instance, 2000AD, I’ve been working for them for about 15 years. I’ve written Judge Dredd, I’ve written characters created by other people. I’ve also created my own characters, most particularly Sinister Dexter and the series Kingdom, things like that, where I set my own ground rules, built my own worlds and have written them successfully ever since. So there is a great freedom there, whereas for Marvel or DC there is this enormous weight of continuity when you pick up a character, you have to go through approvals, you have to make sure you are handling them correctly, which however can be enormously pleasing because I’ve loved Marvel comics particularly, and it is a sheer delight to actually be able to write some of those characters, it’s getting to write something that I’ve wanted to do all my life. Obviously there are other differences, like a Marvel or DC title is a 22 page monthly installment, it’s not just longer because there are 22 pages of it, the whole structure of doing it is different. 2000AD tends to be five or six page weekly installments, so you’re writing a story with a completely different narrative structure, a very different dynamic. There’s a very British feel to 2000AD, which means you can write the kind of stories that no American publisher would necessarily accept – and vice versa: the stories I write for Marvel would not be 2000AD fare at all.

In comics you can write full script, which is something where the writer has complete control over the page. I would number each page of the script, I would number each panel on the page, I would describe what each panel contains, I’d probably tell the artist how big in relation to the other panels on the page I thought it should be and I’d write the dialogue and afterwards it would go the artist to produce. That’s the full script method. The contrasting method is known as the Marvel method, whereby the writer produces a sort of essay, essentially. “On pages 1,2 and 3 Spider-Man does this and this and this, on page 4 he does this, page 5 is a splash page,” and that all goes to the artist who then interprets that and does the storytelling himself, and then the art goes back to the writer who determines specifically the script, what is on the page in terms of the balloons, so it goes writer, artist, writer again. The pros and cons are very simple. One of them gives the writer complete control, or greater control, of the storytelling, and the Marvel method gives the artist greater control of the storytelling, and depending on whether you’re a writer or an artist depends on which version you think is putting the right person behind the wheel. Usually it depends on the relationship between those two people. I have quite happily arrived at whichever scripting form suits depending on the artist I am working with. Some of them want a full script, some of them don’t want a full script, some of them want a lot of detail, some of them don’t want a lot of detail, some of them like to draw something and you make sense of it afterwards, which can be a challenge in itself.

LH: You’re concentrating with Marvel mainly on the cosmic superheroes at the moment. What is it about those that attracts you?

DA: Two things. One is I loved the cosmic books when I was a kid – Jim Starlin writing Captain Marvel, Warlock and characters like that, I absolutely adored that, so an opportunity to take control of those characters and to write them was something I couldn’t really resist. The other thing, and let’s face it, they weren’t being used, these were characters that had been allowed to go stagnant, they’d been overlooked, they weren’t flavour of the month, and therefore there was a great amount to reboot and revive, taking them over, to increase their popularity, to reinvent them for a modern audience without actually breaking what they were in the first place. One of the biggest things that has happened in writing them is the feedback of people who are delighted to read second and third level characters who were being neglected being put into interesting situations, paired up in interesting ways. The Guardians of the Galaxy in particular, we’re quite often complimented on the really odd mix of characters we’ve put together, characters that shouldn’t necessarily work or characters that had been forgotten. One of the great advantages of that of course is that we can do anything with them, within reason, the storylines are much less predictable. We can do the most horrific things to the characters suddenly, without warning, and entertain people with unexpected twists and turns in the story, whereas if you’re writing something that is better known and has a high profile, you’re far more constrained, because unless the character’s going to wake up in the shower there are all sorts of things you can’t do.

LH: The Guardians of the Galaxy has a feel almost going back to the Giffen-DeMatteis JLA of the 1980s. Did you always intend it to be as humorous as it is?

DA: Yes. We were writing that alongside Nova, which is a solo book, which although it’s not without its humour is much more traditional, straightforward superhero-in-space stuff. With a team book, with more characters moving around we had to accommodate more, so we wanted it to be slightly quicker on its feet, to keep people in character much more obviously, which means that the dialogue tends to be slightly more flippant, because there’s a shorthand about keeping these characters in circulation. And also, when you’re dealing with cosmic books, regularly the threat of the week will be the universe is going to die or Galactus is going to eat everybody, there is an enormous operatic scale to things and everything gets so po-faced and serious, you know, “I have the cosmic annilihilator and I am going to obliterate ALL universes, not just this universe but ALL universes,” so to be able to completely undercut that by having characters make off-colour remarks and quipping backwards and forwards and having very fallible personalities seemed the best way of working in that scale. Somehow Galactus seems bigger if you’ve got some little oik at his feet saying something funny rather than someone ponderously saying “I am God of thunder and I will smite thee!”

LH: You collaborate a lot in your comics work with Andy Lanning. How does that work? How do you share the writing duties?

DA: Well I grind the organ… Andy is an artist, we met when I was his editor, when he was drawing for Marvel, Ghostbusters. We shared an enormous enthusiasm for comics that matched, our enthusiasms really fitted together. The stuff we liked was either complementary or propelled each other along. We would go to the pub after a day at work and talk about stories and ideas, and we realized that we had a relationship that would generate ideas very well. He’s an artist as I say, he’s now best known as an inker, that is to say someone who makes pencil artwork camera-ready, not a member of a South American nation. They are popularly dissed as being tracers, but it is an artform of itself, and one that is sadly disappearing in these days of digital stuff, where so much stuff can be taken directly from the pencils, but it is an extraordinary talent. We tend to get together once a week or so for brainstorming sessions that clearly from people who overhear us sound like far too much fun to be work, where we amuse each other and throw ideas, often to the point where we’ll test something to destruction by making fun of it. Then we will work together to plot it and outline it and shape it and pitch it and all the things that need to happen, and what generally happens then is we retire to our separate places of residence and Andy carries on being an inker and I turn the story ideas that we’ve generated into scripts. Sometimes Andy is there plotting and I dialogue after him. There are other ways of doing it, but that’s the basic subdivision. We produce stories that neither one of us would have got to on our own. He’s a wonderful ideas factory, and we are able to push each other. I think that works particularly well with something like cosmic superheroes – we can match each other’s ridiculous, overblown idea and come up with something else or link something tangentially. It’s one of those things that I think we’d have stopped doing years ago if it hadn’t worked – we would have done it for a while and just said that’s great, and then it would have dissolved, but it hasn’t, it’s always stood us in incredibly good stead, so we’ve carried on doing it.

LH: You mentioned earlier that you started out by writing and drawing your own comics. Do you still do any drawing at all? Do you keep your hand in?

DA: Not really, no. I’d love to still draw. In relation to Warhammer, I’d love to play the game more often, to connect to it. One of the essential things I find for being a writer is reading, and if I’m going to do something when I’m not writing it’s going to be reading.

Just in relation to Andy, the other thing that’s kept our relationship going for so long is that there is a terrible cabin fever that can affect most freelancers who work on their own. Particularly in the comics industry you’re always hearing about artists leaving the reservation because they’ve gone stir crazy, they will have disappeared, their editor can’t contact them, there’s seven pages to be finished and they don’t know where they are. I think that just getting together on a regular basis means that we break that for both of our sakes. It is that point of not just human contact but creative contact that keeps us both saner – I wouldn’t say sane, but saner.

LH: You’ve been writing comics now for 25 years. Have you become a cynical old man, or do you still sometimes wake up and think, “Hey! I write superheroes!”?

DA: No, absolutely, I still do. I am very, very lucky to be somebody who is paid for doing something that I would be quite willing to do anyway.

LH: We’ll cut that bit out in case Marvel see it.

DA: Yeah! Inevitably there are days when it’s a horrible job, but you tell that to people and they say, “You write comics for a living! Don’t complain about it!” There are some days when it’s a slog and some days when it’s difficult and whatever, like anything, but I genuinely feel enormous enthusiasm and when somebody gives me the opportunity to write a character I’ve not written before, I suppose I naively believe in them as a creative concept where you are extending an existing continuity rather than just see it as a completely commercial job, and I genuinely enjoy that. In fact Andy and I are just starting a project for Marvel that unfortunately hasn’t been announced yet so I can’t tell you about it*, but it is absolutely packed full of characters like that, and I can’t believe that they are letting us play with these toys, and that is absolutely brilliant, and we promise we won’t break them.

DA: Yeah! Inevitably there are days when it’s a horrible job, but you tell that to people and they say, “You write comics for a living! Don’t complain about it!” There are some days when it’s a slog and some days when it’s difficult and whatever, like anything, but I genuinely feel enormous enthusiasm and when somebody gives me the opportunity to write a character I’ve not written before, I suppose I naively believe in them as a creative concept where you are extending an existing continuity rather than just see it as a completely commercial job, and I genuinely enjoy that. In fact Andy and I are just starting a project for Marvel that unfortunately hasn’t been announced yet so I can’t tell you about it*, but it is absolutely packed full of characters like that, and I can’t believe that they are letting us play with these toys, and that is absolutely brilliant, and we promise we won’t break them.

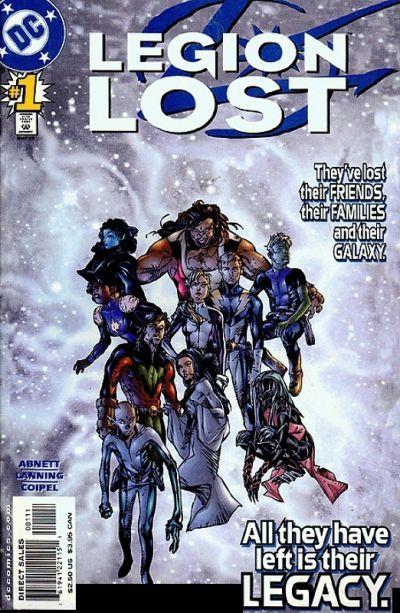

(following an audience question about surprising readers or giving them what they overtly want) In comics, deaths have virtually no meaning at all, because superheroes always come back from the dead. In comics, the great surprise to pull is the unexpected reveal, which is something I’ve delighted in doing every now and then. I remember when I was writing Legion of Super-Heroes for DC, which is set a thousand years in the future of the existing DC universe, the Legion suddenly discovered they were going up against the demon Ra’s Al Ghul, there was this great reveal. He was the only immortal character I could think of who could still be around after a thousand years. They wet their pants when that happened, because he was not a character you expected to turn a page and find in a Legion comic. Taking them out of context like that is a great thing to do, but it made perfect sense. It wasn’t a gratuitous thing, you know, here’s the Joker and somehow he’s been in a freezer for a thousand years, he was a character who could legitimately have been there.

*Might this be the Iron Man/Thor limited series? – Martin Skidmore

Tags: Andy Lanning, Dan Abnett, Guardians of the Galaxy, Nova