Turn That Page!

by Martin Skidmore 11-Dec-10

There is one unique thing about the experience of reading comic books that I’ve not seen discussed a great deal. Books have pages, the same as comics, but they don’t work the same way.

There is one unique thing about the experience of reading comic books that I’ve not seen discussed a great deal. Books have pages, the same as comics, but they don’t work the same way. Short of starting a new chapter, novelists don’t generally know where the page breaks, and there is no special impact when you turn to a new page in a book, since you have to take the time to read it to absorb any information, whereas in comics you grab a lot in the first second. Obviously comic writers and artists are aware of the effect, and most know exactly when they get a double-page spread, which is a left-hand and which a right-hand page, especially today (probably not so much decades ago).

Clearly there are countless examples of creators composing their stories so that there is a striking image, a big moment, when we turn the page. The big splash is no longer on page 1, and it is used for ‘this is what you get this issue!’, or maybe some shocking revelation or twist. Last pages are regularly used in much the same way – shocks, twists, cliffhangers and ‘this is what you’ll get next ish!’

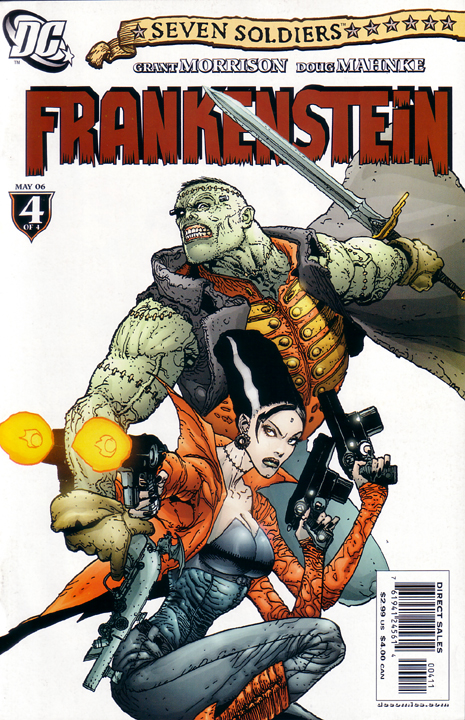

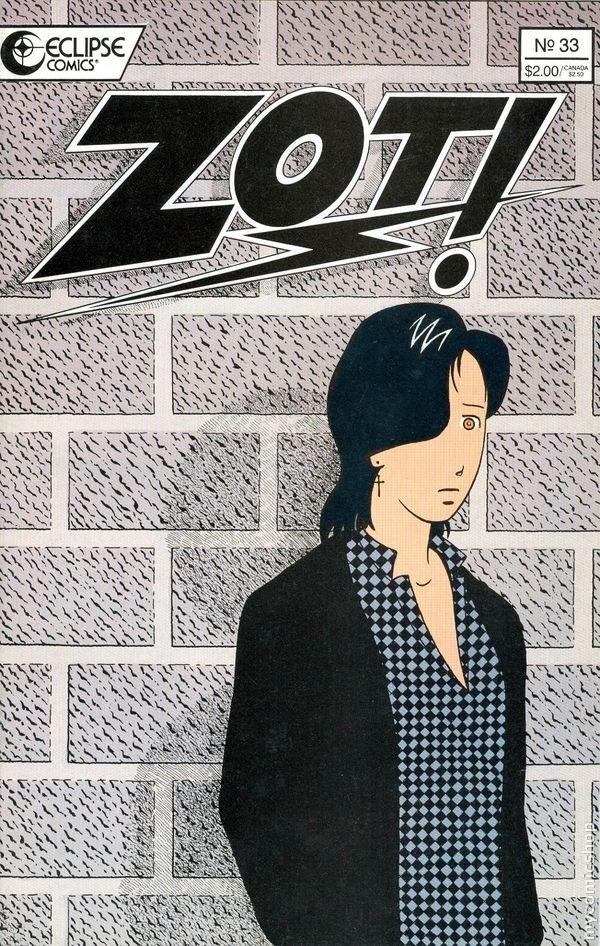

Note: I can’t describe the impact of turning pages without describing some of the contents, so this unavoidably contains spoilers. In particular, if you’ve not read the Seven Soldiers story or Zot! 33 and you are at all likely to, I can only recommend saving this article and buying those comics first. I’ve avoided including any images that act as spoilers.

My favourite page-turning moment ever in comics is probably a double instance, in Frankenstein 4, the 29th in the 30-comic Seven Soldiers epic written by Grant Morrison. I’m sure many know it, and know the pages I am talking about, but for those who don’t, the previous 28 issues had shown us plenty of the world-threatening enemy, the Sheeda, who seemed rather dark-elf in nature, powerful and dangerous faerie creatures appearing from some other realm they call Summer’s End, killing superheroes, talking about the Harrowing. But we had no idea where they came from or just what they were. Then some way into this issue, the last before the finale, Frankenstein is watching a vessel of theirs. We turn a page and get an ad page on the left and one story page with the caption “One billion years later!.” That’s enough of a ‘wow!’ moment, but then he gives us a dense infodump, revealing all the secrets kept for the previous 28 issues, written in darkly poetic language: the Sheeda, it turns out, are the last humans, living on a drained and decayed Earth, surviving by travelling back in time and harvesting the world, wiping out most life on the planet every ten thousand years, existing on the nutrients. We see them getting on their vast dreadnoughts, millions of them ready to attack our time. This is enough of a huge moment, making you recast what is happening, forcing you to reconceive the plot on a huge scale. But then Grant trumps it: you turn the next page and there is a huge double-page image of the titular character with a sword, in this future world, and the caption “All in a day’s work… for Frankenstein!” I laughed out loud when I read this originally, and kept grinning for ages – the last moment I can recall doing that for me in comics is “Gaze into the fist of Dredd!” (and tough if you don’t know that one, I won’t explain them all). Two pages turned, two completely brilliant moments of utterly contrasting kinds. Magnificent.

My favourite page-turning moment ever in comics is probably a double instance, in Frankenstein 4, the 29th in the 30-comic Seven Soldiers epic written by Grant Morrison. I’m sure many know it, and know the pages I am talking about, but for those who don’t, the previous 28 issues had shown us plenty of the world-threatening enemy, the Sheeda, who seemed rather dark-elf in nature, powerful and dangerous faerie creatures appearing from some other realm they call Summer’s End, killing superheroes, talking about the Harrowing. But we had no idea where they came from or just what they were. Then some way into this issue, the last before the finale, Frankenstein is watching a vessel of theirs. We turn a page and get an ad page on the left and one story page with the caption “One billion years later!.” That’s enough of a ‘wow!’ moment, but then he gives us a dense infodump, revealing all the secrets kept for the previous 28 issues, written in darkly poetic language: the Sheeda, it turns out, are the last humans, living on a drained and decayed Earth, surviving by travelling back in time and harvesting the world, wiping out most life on the planet every ten thousand years, existing on the nutrients. We see them getting on their vast dreadnoughts, millions of them ready to attack our time. This is enough of a huge moment, making you recast what is happening, forcing you to reconceive the plot on a huge scale. But then Grant trumps it: you turn the next page and there is a huge double-page image of the titular character with a sword, in this future world, and the caption “All in a day’s work… for Frankenstein!” I laughed out loud when I read this originally, and kept grinning for ages – the last moment I can recall doing that for me in comics is “Gaze into the fist of Dredd!” (and tough if you don’t know that one, I won’t explain them all). Two pages turned, two completely brilliant moments of utterly contrasting kinds. Magnificent.

But really I want to note a couple of other ways these page-turning moments strike a reader or are deliberately used. The first is that you are aware that you are about to turn a page, and sometimes you have an emotional reaction to the expectation you feel, whether it is wanting something or dreading it or whatever. Nothing else works this way – prose can’t offer the quick effect of seeing a comic page, and screen media don’t offer you the control of when you experience that next moment, nor the clear break. Yes, you can pause and resume, but it is rare to even have an undoubted idea of when the key moment is about to come, let alone the ability to stop right there. You don’t have the control of timing in movies and so on, but comics gives you that almost by default.

I’m particularly thinking in this regard of the work of Junji Ito. His manga are my favourite horror stories in any medium, and I was conscious at a few points of genuine reluctance to turn the page, mixed in with excitement and other positive things. A few times I genuinely dreaded what I would see, and I braced myself for it. Sometimes this was a shock that was clearly building up (the shark moment in Gyo would be almost unimaginably spectacular if filmed), sometimes it was the expectation of a genuinely scary image over the page, whether with some idea of what it would be or not. I liked the bonus that these page-turning moments brought to several sections in his comics: stretch the anticipation, feel the dread, ready yourself. I feel the need to note that he is not really a shock-horror type – his speciality is coming up with a bizarre and disturbing idea, then stretching it and seeing it through to extremes beyond anything you would have thought possible. Sometimes you know you are about to be presented the idea you’ve been following taken to a new level, and that is what scares you.

But there is one other device available to cartoonists: not just using the turning of the page, but using the now standard positioning of the letters page signalling the end of the comic. It wasn’t always at the back, but these days you expect that to be the end: you see the letters, you assume that all that is left after it is ads. This struck me recently when reading and reviewing Paul Grist’s The Weird World of Jack Staff, and it was this that got me thinking about this topic. In issue 3, he seems to conclude the story just before the letters page, which appears with just one interior page and the inside and outside back cover left. But if you do turn that final page, there is not advertising but a spread giving you an unexpected and significant coda to the story. He does something similar in #5, though here the extra two pages adds less of substance, I think.

However, the first example I saw of this trick is still the best, although it unfortunately backfired for some readers. Zot! 33 came out in 1990, and barely features the star. Instead it focuses on his girlfriend’s female friend, Terry. A girl has come out at school, and is shunned, including by Terry, who used to be close to her. Terry is struggling with her own lesbian feelings, not very successfully. We get to what seems to be the last page, a left-hand page with letters opposite, and the out girl says hi to Terry, and Terry blanks her and walks on. A desperately sad ending, albeit entirely believable, and one that made some readers toss the comic aside in anger. But if you were to turn over, you’d find one more page, where Terry pulls herself together and speaks to the girl. It’s a small moment, but a huge one emotionally for Terry, and a huge one in terms of the sociology of a school too. Some readers didn’t discover this extra page for days afterwards, and creator Scott McCloud wonders in the Zot! 1987-1991 collection (a hugely recommended purchase if you don’t already have the comics) whether there may still be readers out there unaware of the extra page. This, incidentally, is a wonderful comic throughout, even without the trick ending, sensitively told by a superb craftsman and someone who is honest about how sexual and social politics work in schools, and astute enough to know the colossal difference saying ‘hi’ or not to someone can make.

However, the first example I saw of this trick is still the best, although it unfortunately backfired for some readers. Zot! 33 came out in 1990, and barely features the star. Instead it focuses on his girlfriend’s female friend, Terry. A girl has come out at school, and is shunned, including by Terry, who used to be close to her. Terry is struggling with her own lesbian feelings, not very successfully. We get to what seems to be the last page, a left-hand page with letters opposite, and the out girl says hi to Terry, and Terry blanks her and walks on. A desperately sad ending, albeit entirely believable, and one that made some readers toss the comic aside in anger. But if you were to turn over, you’d find one more page, where Terry pulls herself together and speaks to the girl. It’s a small moment, but a huge one emotionally for Terry, and a huge one in terms of the sociology of a school too. Some readers didn’t discover this extra page for days afterwards, and creator Scott McCloud wonders in the Zot! 1987-1991 collection (a hugely recommended purchase if you don’t already have the comics) whether there may still be readers out there unaware of the extra page. This, incidentally, is a wonderful comic throughout, even without the trick ending, sensitively told by a superb craftsman and someone who is honest about how sexual and social politics work in schools, and astute enough to know the colossal difference saying ‘hi’ or not to someone can make.

I hope I’ll hear about more distinctive uses of the act of turning a page, more special uses of it, in the comments below. I’ll be particularly interested in any devices beyond the few I’ve talked about here.

Tags: Grant Morrison, Junji Ito, Paul Grist, Scott McCloud, Zot

Andy Roberts’ ‘Talking Pages’ in Vicious 6 (back in 1997) went into this. Essentially he argued comics were “narrative’s ideal answer to cubism.”

“A comic page can be taken in all at once, and then examined more closely in whatever order you like. Sequence can be unimportant. What is never unimportant is narrative… so I think the term ‘sequential art’ distracts from this major advantage of comics, this ability to show different viewpoints and events simultaneously.”

Unfortunately it doesn’t seem to be on-line anywhere but it’s worth a read if you can track it down…

That sounds sort of the flip of what I am talking about – obviously his point about absorbing it all at once is essential to what I am saying, but I am trying to discuss the effects that that can bring with it, on that page-turning moment. Obviously he may have addressed that too, of course. I don’t have a copy – was Vicious a zine of some kind?

Yeah, he was talking about the page as a unit, not the interchange between one page and another. It’s a shame its not on-line.

I am keen on looking into the unique features of comics, rather than just copying the tropes of film or theatre or whatever.

Vicious was around in the Nineties, run by Pete Ashton and kind of the loam that Bugpowder sprung from. Like many Nineties things, it was in retrospect in a weird limbo state between old-style fanzines and internet message boards. Pete published all contributions, for example. Also, by then the predominance of the superhero had already been kind of overturned, or at least it was no longer a given. The result was something more factional than old-style fanzines…

In Neonomicon 2, which I reviewed here recently, I found turning the page in the last section increasingly terrifying, as ever more horrible things were happening in the strip.

I also find it interesting that you mention Grant Morrison above, as he is responsible for some of the great OMG page turning moments – like the big reveal about Xorn in X-Men, Robot Archie’s appearence in Zenith, Robot Archie’s reappearence with the dinosaur in Zenith, and I suspect many others.

Yeah, there are lots of great Grant moments like that – I highlighted that particular one mostly because of the double whammy, the two impacts of completely contrasting kinds in every way. His combination of intelligence, love of old comics (their silliness as much as everything else) and respect for thrill power is a rare and potent mixture.