SALLY FORTH! Remembering the UK’s ‘comic for the adventurous girl’

by Will Morgan 16-Dec-21

A break from the traditions of British Girls’ weeklies, Sally emphasised the fantastic and the super-normal, with super-heroines and science-fiction in the spotlight.

For many years, the field of girls’ weekly comics has been unjustly ignored. These titles, which enthralled (and arguably helped to brainwash) generations of girls (and more than a few furtive boys) sold in the hundreds of thousands, every week, capturing huge audiences, but in the field of British comics studies the focus has been overwhelmingly on the boys’ weeklies or the funnies—Eagle, 2000 AD, Beano, ad infinitum.

For many years, the field of girls’ weekly comics has been unjustly ignored. These titles, which enthralled (and arguably helped to brainwash) generations of girls (and more than a few furtive boys) sold in the hundreds of thousands, every week, capturing huge audiences, but in the field of British comics studies the focus has been overwhelmingly on the boys’ weeklies or the funnies—Eagle, 2000 AD, Beano, ad infinitum.

Over the last decade and a half, several writers—Melanie Gibson, Jenni Scott, Julia Round—are mercifully bucking this trend, appreciating the high levels of craftsmanship and storytelling on the distaff side of the market, but even they haven’t yet paid much attention to one of the most sought-after—at least in back-issue sales—girls’ weeklies of all.

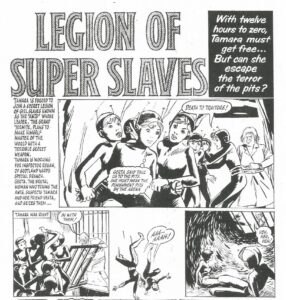

The first issue of Fleetway/IPC’s Sally was dated 14th June 1969, but it had been heavily teased in pre-launch adverts as the ‘comic for the adventurous girl’, and the editors seemed very conscious that they were trying out a different direction. Yes, the usual elements were present: struggling orphans, wandering waifs, and fish-out-of-water stories—‘Daddy Come Home!’, ‘Four On The Road’, ‘Farm Boss Fanny’. But the emphasis was on science-fiction and fantasy themed stories, with two bona-fide super-heroines, two science-fiction tales, and what no less a critic than, oh, me, has previously described as ‘one stonking great heap of bonkers’, specifically ‘The Legion of Super-Slaves!’

… I know you’re going to want to start with that one, right?

Tamara Townsend, gifted 14-year old track star, is kidnapped by agents of the mysterious ‘Grand Termite’, who is building a brainwashed private army to conquer the world. Rather than mercenaries or military or law enforcement—the logical talent pool for such an endeavour—the ‘Grand Termite’ abducts and hypnotises nubile teenage girl athletes and gymnasts, dresses them in skin-tight uniforms, and has them battle for his entertainment—oh, sorry, to prove their ‘worthiness’ for his cause. Obviously a sure path to conquest… if your objective wasn’t, you know, actually conquering anything other than teenage girls! Apparently realizing a mis-step, the editors changed the direction and had Tamara in civvies doing espionage for a while, but after a short but crazed run, ‘Legion of Super-Slaves’ was the first of Sally’s founding strips to falter, the Legion disbanding in the 22nd November 1969 issue.

Tamara Townsend, gifted 14-year old track star, is kidnapped by agents of the mysterious ‘Grand Termite’, who is building a brainwashed private army to conquer the world. Rather than mercenaries or military or law enforcement—the logical talent pool for such an endeavour—the ‘Grand Termite’ abducts and hypnotises nubile teenage girl athletes and gymnasts, dresses them in skin-tight uniforms, and has them battle for his entertainment—oh, sorry, to prove their ‘worthiness’ for his cause. Obviously a sure path to conquest… if your objective wasn’t, you know, actually conquering anything other than teenage girls! Apparently realizing a mis-step, the editors changed the direction and had Tamara in civvies doing espionage for a while, but after a short but crazed run, ‘Legion of Super-Slaves’ was the first of Sally’s founding strips to falter, the Legion disbanding in the 22nd November 1969 issue.

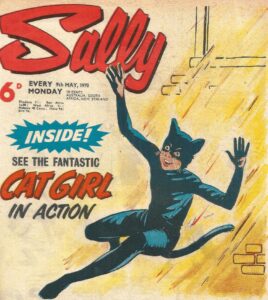

‘Cat Girl’ was basically a younger edition of the 1940s super-heroine Miss Fury. Cathy Carter stumbles across a panther-skin suit gifted to her bumbling private detective father by a narratively convenient former client, an African witch-doctor. Obviously, she tries it on, and obviously it gives her feline attributes, including enhanced senses, balance, dexterity, speed and agility.  Using her powers to help her father’s faltering career, Cathy’s adventures lasted Sally’s entire run and onward into Tammy. A large part of the strip’s appeal was the finely-judged artwork of Giorgio Giorgetti, who gave Cathy and her cohorts an endearingly goofy aspect without making them ridiculous or unsympathetic. Cat Girl, appropriately, had an additional life in Europe, the translated versions of her adventures proving sufficiently popular that some new stories were created specifically for the European market after the end of her UK run.

Using her powers to help her father’s faltering career, Cathy’s adventures lasted Sally’s entire run and onward into Tammy. A large part of the strip’s appeal was the finely-judged artwork of Giorgio Giorgetti, who gave Cathy and her cohorts an endearingly goofy aspect without making them ridiculous or unsympathetic. Cat Girl, appropriately, had an additional life in Europe, the translated versions of her adventures proving sufficiently popular that some new stories were created specifically for the European market after the end of her UK run.

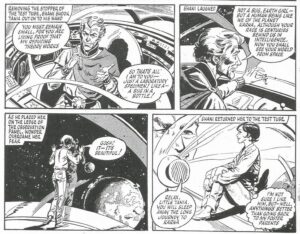

‘Tiny Tania In Space’ and ‘The Girl from Tomorrow’ both had superlative art, detailed but whimsical, by Rodrigo Rodrigue Comos. In ‘Tania’, an orphaned girl runs away from abusive foster-parents and is accosted by an alien scientist who takes her back to his planet Karna, having shrunk her to a few inches in height to demonstrate his new invention.  On Karna, Alaric, young son of another scientist, helps her escape and enlarge again—but residual effects of the shrink-ray hit Tania at unpredictable intervals during her ongoing adventures, alternating between super-power and handicap.

On Karna, Alaric, young son of another scientist, helps her escape and enlarge again—but residual effects of the shrink-ray hit Tania at unpredictable intervals during her ongoing adventures, alternating between super-power and handicap.

‘The Girl From Tomorrow’ (no relation to the 1990s TV show) was Atlanta, a 23rd-century maiden possessed of mind-over-matter powers common in her time (buck up, we’re only two centuries away…), who snoops in her uncle’s lab and gets zapped back to 1969. Her uncle, with a splendid indifference to Child Protection Services, decides to leave her in primitive times for a while to teach her a lesson, and, after Atlanta chums up with falsely-accused young pickpocket Alfie Dommett, the pair have madcap adventures in a charming series very much like a juvenile Bewitched or I Dream of Jeannie.

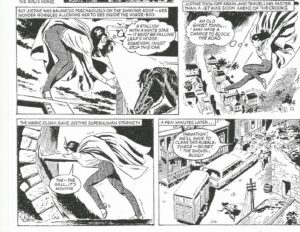

‘The Justice of Justine’ was Sally’s second super-heroine. Young Justine Jones aids a mysterious old man, accompanies him to a cave (caution; not a scenario usually resulting in super-powers—Just Say No, Kids!) and is rewarded with four magical artefacts; a cloak giving her flight, great strength, and courage; goggles which give her mystically enhanced vision; a bow & arrows which induce sleep; and a mirror which serves as a supernatural pager, summoning her to her next mission. Alone among the main Sally series, Justine lacked a consistent artist—her two-part adventures were illustrated by several people, and although the roster included some distinguished names (John Burns, John Armstrong, Mike Noble), this unevenness, plus the changeability of her powers (flight and strength were constant, but others came and went as the plot demanded, and one—talking to animals—just popped up without any explanation!), may have prevented the series gaining a greater following.

‘The Justice of Justine’ was Sally’s second super-heroine. Young Justine Jones aids a mysterious old man, accompanies him to a cave (caution; not a scenario usually resulting in super-powers—Just Say No, Kids!) and is rewarded with four magical artefacts; a cloak giving her flight, great strength, and courage; goggles which give her mystically enhanced vision; a bow & arrows which induce sleep; and a mirror which serves as a supernatural pager, summoning her to her next mission. Alone among the main Sally series, Justine lacked a consistent artist—her two-part adventures were illustrated by several people, and although the roster included some distinguished names (John Burns, John Armstrong, Mike Noble), this unevenness, plus the changeability of her powers (flight and strength were constant, but others came and went as the plot demanded, and one—talking to animals—just popped up without any explanation!), may have prevented the series gaining a greater following.

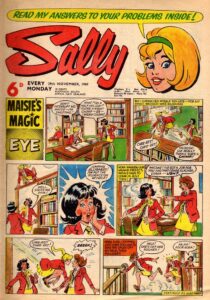

An honourable mention must go to ‘Maisie’s Magic Eye’. While not sci-fi, and barely fantasy, the comedic adventures of Maisie MacRae proved to be the breakout hit of Sally, going on into Tammy and running for years. Primarily drawn by Robert MacGillivray, Maisie found a fragment of a meteorite and made it into a brooch—as you would—which, when glowing, compelled others to do as Maisie commanded.  This reboot of ‘Mimi the Mesmerist’ swiftly expanded its remit, however, as in later episodes the ‘Eye’ not only commanded obedience, but proved able to travel through time, transform objects or people, and generally re-write reality—so of course Maisie used it to avoid extra PE, or take petty revenge on nagging prefects! Many stories stemmed from misunderstandings when Maisie expressed an impulsive wish without realizing her literal-minded brooch was glowing. All avoidable if she’d learned to, oh, I don’t know, STFU and check her blouse before speaking!

This reboot of ‘Mimi the Mesmerist’ swiftly expanded its remit, however, as in later episodes the ‘Eye’ not only commanded obedience, but proved able to travel through time, transform objects or people, and generally re-write reality—so of course Maisie used it to avoid extra PE, or take petty revenge on nagging prefects! Many stories stemmed from misunderstandings when Maisie expressed an impulsive wish without realizing her literal-minded brooch was glowing. All avoidable if she’d learned to, oh, I don’t know, STFU and check her blouse before speaking!

It was a strong and engaging line-up, and a genuine attempt to do something different… but alas, the experiment was short-lived.

With the issue dated 17th January 1970, ‘Justice of Justine’, ‘Tiny Tania In Space’ and ‘The Girl from Tomorrow’ were all axed, bringing the sf-centric iteration of Sally to a close. They were replaced by ‘Schoolgirl Princess’ (later ‘Sara’s Kingdom’, as our heroine ascended to the throne), ‘The Silent Shadows’ (another band of plucky schoolgirls thwarting the Reich in the Second World War—it’s a wonder the Nazis ever got anything done!) and ‘The Ghost Hunters’ (a US/UK girl duo investigating spooky doings). All quality strips, but all, it has to be said, safe bets, taste-alike versions of what had been done many times before. The editors, after slightly less than half a year, had clearly decided that the audience just wasn’t out there, and fell back on business as usual.

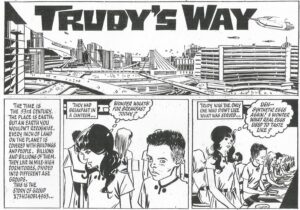

There was one more attempt at SF, commencing 19th September 1970; ‘Trudy’s Way’ featured an idealistic and imaginative girl in the desperately overcrowded Earth of the 53rd Century. Selected for a colonial expedition, she encourages her shipmates to overcome their fears and embrace a less regimented, more natural lifestyle. An interesting concept, swiftly ended after nine episodes, clearly not clicking with readers.

There was one more attempt at SF, commencing 19th September 1970; ‘Trudy’s Way’ featured an idealistic and imaginative girl in the desperately overcrowded Earth of the 53rd Century. Selected for a colonial expedition, she encourages her shipmates to overcome their fears and embrace a less regimented, more natural lifestyle. An interesting concept, swiftly ended after nine episodes, clearly not clicking with readers.

Sally itself went on until the 27th March 1971, as a well-done but un-exceptional weekly. Its circulation had been hampered by a ten-week printers’ strike preventing new issues between late ’70 and early ’71, and it never really regained lost ground. It was absorbed into the upstart Tammy—back then, only months old—with ‘Cat Girl’, ‘Maisie’, comedy one-pager ‘Lulu’ and ‘Sara’s Kingdom’ making the jump. All but Maisie were gone by the end of 1972.

Gone, but not quite forgotten. Cat Girl appeared in the 1989/1990 Phase III of Morrison and Yeowell’s ‘Zenith’ in 2000 AD, meeting an unfortunate end in an underground station, and both Justine and Maisie had cameo appearances in Leah Moore and John Reppion’s Albion in 2005.

Justine and Maisie also returned in 2019’s Tammy & Jinty Special, in all-new stories—albeit not quite as we remember them—and a second-generation Cat Girl, daughter of Cathy Carter (who’s now a copper!) was the lead in 2020’s T & J Special.

Not a huge success during its initial run, Sally—especially the issues up to 17th January 1970—is now hotly sought-after by back-issue collectors. At a short achievable run (83 issues, 1 Summer Special, 6 Annuals and two spin-offs—a Cookbook and a Book of Pets), with many high-quality creators, it has considerable collector appeal, and is well remembered. A promising sign is that Rebellion, the company dedicated to excavating panelelological treasures, has announced a Best of Cat Girl compilation paperback for August 2022!

Not a huge success during its initial run, Sally—especially the issues up to 17th January 1970—is now hotly sought-after by back-issue collectors. At a short achievable run (83 issues, 1 Summer Special, 6 Annuals and two spin-offs—a Cookbook and a Book of Pets), with many high-quality creators, it has considerable collector appeal, and is well remembered. A promising sign is that Rebellion, the company dedicated to excavating panelelological treasures, has announced a Best of Cat Girl compilation paperback for August 2022!

Let’s hope it’s simply the first of many.

Tags: Cat Girl, Ghost Hunters, girls comics, Justice of Justine, Legion of Super Slaves, Maisie's Magic Eye, Sally, Sara's Kingdom, Silent Shadows, Tammy, The Girl From Tomorrow, Tiny Tania in Space, Trudy's Way, UK Comics