More Than Watchmen, Moore, and Miller: Some semi-forgotten superhero comics of the early 1980s

by Tony Keen 23-Apr-22

The early 1980s were a boom period for superhero comics. They have been overshadowed by the work of Alan Moore and Frank Miller later in the decade, but they deserve more attention.

Ah, the 1980s. A great period for comics, eh? The time of Alan Moore on Captain Britain, Marvelman (or Miracleman, as it retrospectively became), Swamp Thing, his Superman Annual, Watchmen and The Killing Joke, Frank Miller on Daredevil, Dark Knight,* Elektra: Assassin, Daredevil: Born Again and Batman: Year One, and at the very end of the decade, Neil Gaiman on Black Orchid and Sandman, and Grant Morrison on Zenith, Animal Man, and Arkham Asylum. Well, yes, but, as I said when I was on a panel at the 2016 Eastercon (the British National Science Fiction Convention) discussing the 1980s in comics, that’s what everyone always talks about, and those don’t need any more exposure from me. I’m here to tell you that there’s so much more to the 1980s than the work of those four writers. (And also, the end of Watchmen has some serious problems, and Black Orchid is massively derivative, the work of a writer yet to find his own voice.) I want to talk about some semi-forgotten superhero comics of the early 1980s, the ones that are now slightly under the radar.

Ah, the 1980s. A great period for comics, eh? The time of Alan Moore on Captain Britain, Marvelman (or Miracleman, as it retrospectively became), Swamp Thing, his Superman Annual, Watchmen and The Killing Joke, Frank Miller on Daredevil, Dark Knight,* Elektra: Assassin, Daredevil: Born Again and Batman: Year One, and at the very end of the decade, Neil Gaiman on Black Orchid and Sandman, and Grant Morrison on Zenith, Animal Man, and Arkham Asylum. Well, yes, but, as I said when I was on a panel at the 2016 Eastercon (the British National Science Fiction Convention) discussing the 1980s in comics, that’s what everyone always talks about, and those don’t need any more exposure from me. I’m here to tell you that there’s so much more to the 1980s than the work of those four writers. (And also, the end of Watchmen has some serious problems, and Black Orchid is massively derivative, the work of a writer yet to find his own voice.) I want to talk about some semi-forgotten superhero comics of the early 1980s, the ones that are now slightly under the radar.

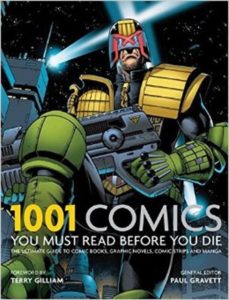

This article has its roots in a reaction to 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die (2011); in general, a fascinating work, but in places quite frustrating. In the editorial introduction to the volume, Paul Gravett talks about how the book can be used not just as a guide to what to read, but as a history of the medium. But as I read the work, I found that as a history of superhero comics, it was seriously lacking.

This article has its roots in a reaction to 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die (2011); in general, a fascinating work, but in places quite frustrating. In the editorial introduction to the volume, Paul Gravett talks about how the book can be used not just as a guide to what to read, but as a history of the medium. But as I read the work, I found that as a history of superhero comics, it was seriously lacking.

It doesn’t help that some entries end up in the wrong order. Though all the articles are grouped under years, they are not carefully ordered within each year. So, for instance, under 1941, Wonder Woman appears before Captain America—whereas Cap actually was first published nearly a year before the Amazonian Princess, and, as I’ve argued in a previous article for FA, Diana’s costume was influenced by Captain America and the slew of star-spangled heroes he inspired. As another example, under 1986, Frank Miller and David Mazzuchelli’s Batman: Year One appears before the same team’s Daredevil: Born Again, implying that Mazzuchelli got the Daredevil gig as a result of his work on Batman; the reality is, of course, the other way round (indeed, all of Year One was cover-dated 1987, though the vagaries of comics publication meant that the first issue appeared at the end of 1986).

It’s in the area of the early 1980s superhero comic that I find 1001 Comics most frustrating. There is a very strong implication that, once John Byrne left X-Men in 1981, nothing much happened until Alan Moore began writing Swamp Thing in 1983, and after that not much more until 1986’s double-whammy of Watchmen and Dark Knight. The book then devotes several pages to 1986-1987, an extremely fertile two years for Moore and, especially, for Miller. (I admit that until reading 1001 Comics I hadn’t realised quite how intense was Miller’s period of great creativity around this time.)

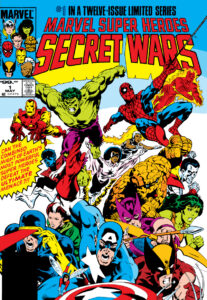

The early ’80s, then, are presented as a sort of cultural desert in terms of superhero comics. Even Miller’s own first run on Daredevil, massively influential at the time, doesn’t warrant a mention. In my view, a fairer picture is that after the doldrums of the late 1970s, where there was little worth getting excited about beyond X-Men and the Steve Englehart/Marshall Rogers run on Batman in Detective Comics, the early 1980s were a period of great innovation in superhero comics. Yes, there was some rubbish, in fact, quite a lot of rubbish, such as Dazzler or Secret Wars—the latter a stupid idea then and a stupid idea in the 2010s. But there were also a lot of good comics, which in many ways laid the groundwork for what Moore and Miller (and Gaiman and Morrison) were to do. And the early ’80s are often a lot more fun than the unremitting grimness that followed Watchmen and Dark Knight.

The early ’80s, then, are presented as a sort of cultural desert in terms of superhero comics. Even Miller’s own first run on Daredevil, massively influential at the time, doesn’t warrant a mention. In my view, a fairer picture is that after the doldrums of the late 1970s, where there was little worth getting excited about beyond X-Men and the Steve Englehart/Marshall Rogers run on Batman in Detective Comics, the early 1980s were a period of great innovation in superhero comics. Yes, there was some rubbish, in fact, quite a lot of rubbish, such as Dazzler or Secret Wars—the latter a stupid idea then and a stupid idea in the 2010s. But there were also a lot of good comics, which in many ways laid the groundwork for what Moore and Miller (and Gaiman and Morrison) were to do. And the early ’80s are often a lot more fun than the unremitting grimness that followed Watchmen and Dark Knight.

I want to make this case through three main examples. It is probably inaccurate to say that these series are ‘under the radar’. All of these are comics that were fêted at the time, critically highly praised and award-winning. They remain highly influential, and have all been collected and can be purchased and read easily today. Yet I would argue that they do get neglected in a discourse that all too often fails to get past Moore and Miller. (I would also add that all three of my examples went on long past their sell-by date.)

Those three examples are John Byrne’s Fantastic Four, Walt Simonson’s Thor, and Marv Wolfman and George Pérez’s New Teen Titans.

Though John Byrne has more recently revealed himself as a transphobic git, comparing trans people to paedophiles, in 1981 he was a superstar comics artist. His run with Chris Claremont on Uncanny X-Men had been spectacular, culminating in the Dark Phoenix Saga, which was plundered for the movies X-Men: The Last Stand and Dark Phoenix, and then ‘Days of Future Past’, which also formed the basis for a recent X-Men movie. Readers at the time had probably not realised the degree to which Byrne was contributing to the plotting of the comic, though it soon became obvious once he left and the quality of X-Men plummeted.

Byrne moved on to what had once been Marvel’s flagship title, the first Silver Age superhero title created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, Fantastic Four. FF, the self-styled ‘World’s Greatest Comic Magazine’, was in serious trouble in the early 1980s. Mindblowing in the 1960s, the cosmic concepts that characterised the series had become dull in the hands of the likes of Marv Wolfman and Bill Mantlo. The FF themselves, pretty much static in their membership, lacked the dynamism of a team such as the Avengers.

Byrne moved on to what had once been Marvel’s flagship title, the first Silver Age superhero title created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, Fantastic Four. FF, the self-styled ‘World’s Greatest Comic Magazine’, was in serious trouble in the early 1980s. Mindblowing in the 1960s, the cosmic concepts that characterised the series had become dull in the hands of the likes of Marv Wolfman and Bill Mantlo. The FF themselves, pretty much static in their membership, lacked the dynamism of a team such as the Avengers.

In 1979 and 1980, Byrne had pencilled a few issues of FF (often only producing loose layouts), but in 1981 came back to write and draw the book, including inking his own pencils. This was a significant change; for over a decade the inking on FF had been done by Joe Sinnott, and the look of the book was more Sinnott than any of the pencillers who had worked on the title after Kirby himself. Now, under Byrne, it looked more realistic, less like a ’60s comic.

Byrne entered with an overt ‘back to the basics’ approach. In particular, he recognised that the FF are not a professional organization of superheroes, as the Avengers are, but a family who happen to possess superpowers. He also returned dynamism to the book. An attempt to restore Ben Grimm, the Thing, to human form, instead reverted him for a while to his original 1963 appearance. Ben’s Aunt Petunia, one of the classic unseen characters of comics, was brought onto the page, turning out to be much younger than any reader had imagined. Frankie Raye, girlfriend of Johnny Storm, the Human Torch, acquired superpowers of her own, before becoming the herald of the world-devouring Galactus. New costumes were introduced, which stuck around until the 1990s. The Thing was replaced by She-Hulk. Alicia Masters, long-time girlfriend of Ben Grimm, became involved with Johnny Storm (though it was later retconned that this was actually a shape-changing Skrull, something that rather betrays Byrne’s intentions). All of this was delivered with quite a touch of humour.

Along the way, Byrne gave the readers several entertaining stories. The twentieth anniversary issue in 1981 features an excellent Doctor Doom tale, and there’s also a fine four-part Negative Zone adventure.

I have two favourite narratives from the time. First is a Galactus story (Fantastic Four #257, August 1983) in which the FF don’t feature directly, though it has ramifications for them. Led by his herald Nova (the former Frankie Raye), Galactus comes to a new planet which he will consume. It happens to be the Throneworld of the Skrulls, one of the major galactic empires of the Marvel Universe. The destruction of the Throneworld, and the death of Princess Anelle, who had once been the love interest of the 1970s Captain Marvel, remains a shocking moment (though since retconned away). The follow-up is a bit less impressive. Reed Richards, Mr Fantastic, is put on trial, for he had previously saved Galactus when the latter was dying. Byrne resolved the trial storyline with a not wholly satisfactory revelation that Galactus is part of the universe and must survive but no-one can quite say why because it’s too cosmic or something.

I have two favourite narratives from the time. First is a Galactus story (Fantastic Four #257, August 1983) in which the FF don’t feature directly, though it has ramifications for them. Led by his herald Nova (the former Frankie Raye), Galactus comes to a new planet which he will consume. It happens to be the Throneworld of the Skrulls, one of the major galactic empires of the Marvel Universe. The destruction of the Throneworld, and the death of Princess Anelle, who had once been the love interest of the 1970s Captain Marvel, remains a shocking moment (though since retconned away). The follow-up is a bit less impressive. Reed Richards, Mr Fantastic, is put on trial, for he had previously saved Galactus when the latter was dying. Byrne resolved the trial storyline with a not wholly satisfactory revelation that Galactus is part of the universe and must survive but no-one can quite say why because it’s too cosmic or something.

My other favourite is also connected with the Skrulls. In the second issue of Fantastic Four in 1961, the FF first encountered the shape-shifting Skrulls. At the end of the story, the FF hypnotised three Skrulls into becoming dairy cows. In FF Annual #17 (1983), his first FF Annual, Byrne explored what happened when local people drank the milk that these Skrulls produced, acquiring Skrull-like shape-shifting powers.

My other favourite is also connected with the Skrulls. In the second issue of Fantastic Four in 1961, the FF first encountered the shape-shifting Skrulls. At the end of the story, the FF hypnotised three Skrulls into becoming dairy cows. In FF Annual #17 (1983), his first FF Annual, Byrne explored what happened when local people drank the milk that these Skrulls produced, acquiring Skrull-like shape-shifting powers.

Sadly, from 1984, a decline set in, as Byrne was over-committed to other titles, running out of ideas, and becoming increasingly dissatisfied with corporate interference from higher up in Marvel. He carried in for another two years, but this material isn’t really worth seeking out. The first three years are the best. The two Fantastic Four movies of the 2000s owe a lot to Byrne’s work.

Even more influential on later superhero movies is my second example, Walter Simonson’s The Mighty Thor. When first launched in 1962, Thor recounted the adventures of the Norse Thunder God, brought to modern New York and finding himself functioning as a superhero. Thor had to balance involvement in contemporary Earth with his responsibilities in Asgard, and an increasing tendency to get involved in cosmic space opera. This had been brilliant in the 1960s, when Jack Kirby had been in charge of it (it’s a fairly safe bet that Stan Lee’s involvement in Thor was minimal). But by 1983 Thor was probably in an even worse state than FF had been when Byrne took over. Just before Simonson’s arrival, this very website’s founder, comics fan and critic Martin Skidmore, detailed what was wrong in a perceptive piece called ‘Why is Thor Boring?’.

Walt Simonson, like Byrne, was a well-known artist, best remembered at the time for his work on Manhunter, a series that had appeared as a back-up in DC’s Detective Comics in 1973. He had done some writing, primarily comics adapting the television science fiction series Battlestar Galactica. But the 1980s were a time when many artists were able to become writer/artists. Byrne is an example—another is Frank Miller, who got his opportunity with Daredevil. And Simonson was given his chance with Thor.

Walt Simonson, like Byrne, was a well-known artist, best remembered at the time for his work on Manhunter, a series that had appeared as a back-up in DC’s Detective Comics in 1973. He had done some writing, primarily comics adapting the television science fiction series Battlestar Galactica. But the 1980s were a time when many artists were able to become writer/artists. Byrne is an example—another is Frank Miller, who got his opportunity with Daredevil. And Simonson was given his chance with Thor.

Like Byrne, Simonson took a ‘back to basics’ approach. In the case of Thor, that meant turning to the Norse mythology from which Thor emerged.† Kirby had made this a key part of his version, especially in the back-up strip Tales of Asgard. Simonson integrated this stuff into the main storylines, and for the first time in fifteen years, Thor and his supporting cast felt like mythological beings, and not just a superhero and some powerful and not-so-powerful figures around him.

And like Byrne, Simonson innovated. In his very first story, he introduced the alien Beta Ray Bill. It had always been established that Thor’s power came from his being worthy enough to hold his enchanted hammer Mjolnir, and that, in theory, that power could be wielded by anyone who was worthy. But that theory had never been explored until Simonson, when he had Bill pick up the walking stick of Don Blake, Thor’s alter ego, which was Mjolnir in disguised form. Bill struck the stick against a wall, and gained Thor’s power. That led to a shake-up of Thor’s earthly set-up, that removed the silly device of Thor turning back into Don Blake whenever he let go of Mjolnir for sixty seconds. Blake was taken out of the picture, at least for a bit, along with, for a while, Thor’s earthly love interest Jane Foster. Thor himself gained a new secret identity. And that leads to an amusing moment where Thor, unconvinced by Nick Fury’s suggestion that simply putting on glasses will work as a disguise, unknowingly bumps into someone for whom that disguise had, at that point, worked for nearly half a century.

Simonson followed up these preliminaries with his Ragnarok story, which he began hinting at early in his run, before finally delivering its climax in 1985. The threat of Ragnarok, the Twilight of the Gods, had always been part of the Thor mythos in the comics, as it has always been part of the wider Norse mythology, and false Ragnarok after false Ragnarok had been and gone in the 1970s, none of them very memorable. Kirby had wanted to do Ragnarok for real in the 1960s, and when Stan Lee wouldn’t let him, he had taken the idea to DC, where he had reworked it as New Gods.

Simonson followed up these preliminaries with his Ragnarok story, which he began hinting at early in his run, before finally delivering its climax in 1985. The threat of Ragnarok, the Twilight of the Gods, had always been part of the Thor mythos in the comics, as it has always been part of the wider Norse mythology, and false Ragnarok after false Ragnarok had been and gone in the 1970s, none of them very memorable. Kirby had wanted to do Ragnarok for real in the 1960s, and when Stan Lee wouldn’t let him, he had taken the idea to DC, where he had reworked it as New Gods.

Simonson made Ragnarok work by, once again, returning to the mythology. He gives a key role to the fire giant Surtur, as is the case in the earliest versions of the Norse story. This epic provides classic moments such as when Thor and Loki, rivals and often enemies, line up beside their father Odin to face Surtur, and their joint cry when Odin falls into the fiery hell of Muspelheim.

The complexity given to Loki, a one-dimensional villain before this point, is a major achievement of Simonson’s run. This portrayal influences how Loki has since been depicted in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Indeed, much of Simonson’s Thor is reproduced in the MCU, though the movies ditch the cod-Shakespearian that Simonson had merely toned down, and bring back Jane Foster.

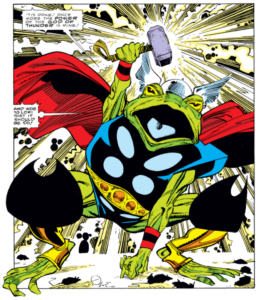

Arguably Somnson’s Thor went off the boil a bit after the Ragnarok story, especially once Sal Buscema replaced Simonson as artist. Some see the shark-jumping moment as a 1986 story where Thor was transformed into a frog, and became involved in a war in Central Park between frogs and rats, before then transforming into a six-foot tall Thunder Frog. I remember a particularly scathing review of this sequence in some critical magazine or other that condemned the narrative for treating animals as intelligent life, and therefore introducing philosophical questions about the rights and wrongs of killing animals for food that had no place in the Marvel Universe.‡ This is possibly an excessive criticism, and the story, whilst not Simonson’s greatest, fits solidly into a mythological tradition of beast fables, and clearly references the Greek Batrachomyomachia, the Battle of Frogs and Mice, a parody of mythological epic.§

Arguably Somnson’s Thor went off the boil a bit after the Ragnarok story, especially once Sal Buscema replaced Simonson as artist. Some see the shark-jumping moment as a 1986 story where Thor was transformed into a frog, and became involved in a war in Central Park between frogs and rats, before then transforming into a six-foot tall Thunder Frog. I remember a particularly scathing review of this sequence in some critical magazine or other that condemned the narrative for treating animals as intelligent life, and therefore introducing philosophical questions about the rights and wrongs of killing animals for food that had no place in the Marvel Universe.‡ This is possibly an excessive criticism, and the story, whilst not Simonson’s greatest, fits solidly into a mythological tradition of beast fables, and clearly references the Greek Batrachomyomachia, the Battle of Frogs and Mice, a parody of mythological epic.§

Generally, in terms of the idea of the title’s decline, it’s worth noting Woodrow Phoenix’s reviews on the Slings and Arrows website of the last two volumes, #4 and #5, of the collected editions of Simonson’s Thor. Whilst Phoenix acknowledges a slight drop-off in quality towards the end, he feels that even then it remains very high.

My first two examples have been Marvel series; my third, New Teen Titans, comes from their rivals, DC Comics. DC had come through the 1970s in a far worse shape than Marvel, despite the occasional success, such as Green Lantern/Green Arrow. They were seen as outdated, compared to Marvel’s hipness, and were losing market share without any good way of getting it back.

My first two examples have been Marvel series; my third, New Teen Titans, comes from their rivals, DC Comics. DC had come through the 1970s in a far worse shape than Marvel, despite the occasional success, such as Green Lantern/Green Arrow. They were seen as outdated, compared to Marvel’s hipness, and were losing market share without any good way of getting it back.

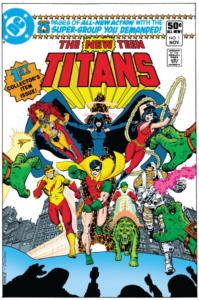

Around 1980, that started to change. DC began offering some royalties on their best-selling comics, where Marvel remained strictly work-for-hire. At the same time, Marvel, once the home of youthful artistic freedom, became progressively more corporate in its internal processes. The combination of these two factors tempted some key talent over to DC, and New Teen Titans is the product of three of these creators, editor Len Wein, who as a writer had co-created the new X-Men, writer Marv Wolfman, most famous for Tomb of Dracula, and penciller George Pérez. The last of these was still under thirty, and known to Wolfman from having drawn Wolfman’s Fantastic Four scripts at Marvel (though he was most famous at the time for his later work on Avengers). New Teen Titans was to turn Pérez into a comics superstar.

The original Teen Titans had been a team-up of various DC sidekicks, such as Green Arrow’s partner Speedy, Aqualad, Robin, the first Bat-Girl (not the Barbara Gordon version), etc. It had been known for the silliness of its plots, and whilst it had sold well, had been a bit of an embarrassment to the company. The revival ditched all but three of the original cast (Robin, Kid Flash, and Wonder Girl), added a teen member of the then-defunct Doom Patrol, and brought in three wholly new characters. Where the old series had presented the Titans as fourteen or fifteen, these Titans were eighteen or nineteen, beginning to find their way in the world, becoming sexually active, etc. In that, it shared a lot with Marvel’s X-Men, which was a model in many other ways. New Teen Titans brought a certain attitude to the storytelling, one that had certainly not been seen in Teen Titans before and rarely in any DC comic. It’s pretty clear in retrospect that Wein, Wolfman and Pérez’s intention was to create a Marvel-style comic in the DC Universe.

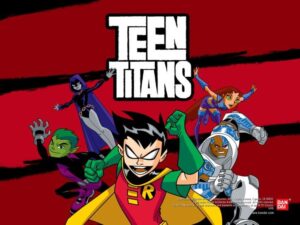

And they succeeded. Teen Titans has much of the feel of a Marvel comic, and does it well. It soon became a massive hit. Four years later it was one of the first of DC’s titles to be issued on better paper than the newsprint then typical of comics. The Teen Titans line-up that was created in 1980 is pretty much the same line-up as can be found in the popular animated tv series Teen Titans Go!, though that has reduced their ages. The ongoing television series Titans (2018-) owes much to Wolfman and Pérez’s work. One of their new characters, Cyborg, appeared in 2017’s Justice League movie and the 2019 Doom Patrol tv series. And ever since the early 1980s, DC comics have been stylistically much closer to Marvel.

And they succeeded. Teen Titans has much of the feel of a Marvel comic, and does it well. It soon became a massive hit. Four years later it was one of the first of DC’s titles to be issued on better paper than the newsprint then typical of comics. The Teen Titans line-up that was created in 1980 is pretty much the same line-up as can be found in the popular animated tv series Teen Titans Go!, though that has reduced their ages. The ongoing television series Titans (2018-) owes much to Wolfman and Pérez’s work. One of their new characters, Cyborg, appeared in 2017’s Justice League movie and the 2019 Doom Patrol tv series. And ever since the early 1980s, DC comics have been stylistically much closer to Marvel.

It is true that some of the Titans’ villains, for instance Trigon the Terrible and Brother Blood, are, when it comes down to it, a touch on the silly side. But that doesn’t matter, because the stories built around them are solid superhero fare, and sometimes even better than that, as in the long story arc in which (spoiler alert) the Titans admit a new member who betrays them.

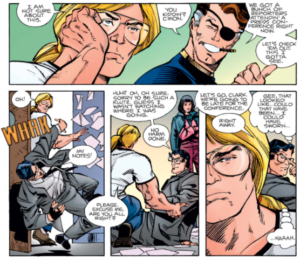

In any case, the very best Titans stories weren’t the standard superhero narratives—instead, they were those that most ditched those modes of storytelling. I speak in particular of two stories. One is the classic ‘Runaways’, which ran in #26 (December 1982) and 27 (January 1983). This two-parter (which was my first exposure to Teen Titans) did what it said on the tin—told the story of some teen runaways who happened to cross paths with the Titans. It’s open, honest, unsentimental and heart-breaking.

The other issue that deserves highlighting is ‘Who Is Donna Troy?’ in #38 (January 1984), an investigation into Wonder Girl’s origins. Again, there are almost no superheroics, but tons of genuinely affecting emotion. It’s a deserved classic.

The other issue that deserves highlighting is ‘Who Is Donna Troy?’ in #38 (January 1984), an investigation into Wonder Girl’s origins. Again, there are almost no superheroics, but tons of genuinely affecting emotion. It’s a deserved classic.

Inevitably, Titans fell apart. Pérez left in 1985, and it became obvious how much input he had into the plotting. Wolfman stayed with the title for another decade, but quality plummeted, and no-one much cares about the post-Pérez material (it hasn’t ever been collected, apart from material after Pérez returned in 1988). But for the first half of the decade, Teen Titans was one of the titles that pushed DC ahead of Marvel in the overall quality stakes, a key factor in attracting Miller, Moore, Morrison and Gaiman over to work for DC.

I hope that this brief run through has encouraged you to try out these comics, if you haven’t already. And perhaps you’ll try some other comics from this period, such as Roger Stern and John Byrne’s all-too-brief run on Captain America, which showed more understanding of the character than had been seen for a decade, and made me a Cap fan for life (it’s collected as War & Remembrance). Or there’s Stern’s run as writer of Avengers (also collected), probably the most consistent period in the comic’s history since Steve Englehart left in 1976.

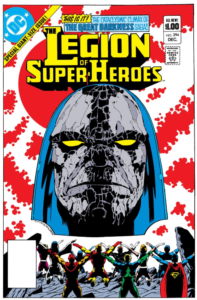

Over at DC, there’s Paul Levitz and Keith Giffen’s run on Legion of Superheroes, the other jewel besides Teen Titans in DC’s crown (try The Great Darkness Saga for size). Or Doug Moench’s 1983-1986 run on the two Batman titles, Detective Comics and Batman, where stories crossed over from one to the other, effectively creating a fortnightly Batman comic, an innovation I wish had been tried more often when the same character stars in different books. Sadly this is uncollected, though Moench’s 1990s run on Batman with Kelley Jones is available.

Over at DC, there’s Paul Levitz and Keith Giffen’s run on Legion of Superheroes, the other jewel besides Teen Titans in DC’s crown (try The Great Darkness Saga for size). Or Doug Moench’s 1983-1986 run on the two Batman titles, Detective Comics and Batman, where stories crossed over from one to the other, effectively creating a fortnightly Batman comic, an innovation I wish had been tried more often when the same character stars in different books. Sadly this is uncollected, though Moench’s 1990s run on Batman with Kelley Jones is available.

Criminally, also uncollected is Bob Rozakis and Stephen DeStefano’s ’Mazing Man. If you haven’t read this, I’m afraid no description of mine can do this charming, funny delight justice. Just seek it out, okay?

There were a lot of poor comics around in the early 1980s, and the likes of Miller and Moore were reacting against this in what they did. But they were also benefiting from those that had gone immediately before them, who paved the way for quality superhero comics that explored what the genre could do. If nothing else, these predecessors proved that good comics could sell, something that seemed not to be the case in the 1970s. There is quality there, and it is worth reading.

This article originally appeared in Claims Department 19 (March 2017), edited by Chris Garcia. Our thanks to Chris for allowing the article to be reproduced here. This version has been thoroughly revised.

* Pedant alert: When originally published, The Dark Knight Returns was merely the title of the first issue of a series called Batman: The Dark Knight. Only with the collected edition did Dark Knight Returns become the title of the whole series.

† If you are interested in learning more about the original Norse myths, I recommend the recent retellings of them by Neil Gaiman.

‡ I thought this article was in one of the Fantagraphics critical magazines, either the Comics Journal or, more likely, Amazing Heroes, but I have subsequently tried and completely failed to find it. Nevertheless, I know it exists. If anyone can help me find it, I would be most grateful.

§ This is discussed by Nicholas Newman in an article in New Voices in Classical Reception Studies for 2020.