Phoenix

by Martin Skidmore 06-Mar-11

Osamu Tezuka’s Phoenix is the greatest unfinished work in comics (and a real contender for comics’ greatest work of any kind). Don’t let the lack of a conclusion put you off – each volume is self-contained, though there are gains to be had from reading them all, in that characters recur, as do the central themes of reincarnation and questing for immortality, all centred on the mythical bird of the title, whose blood allegedly confers immortality.

Osamu Tezuka’s Phoenix is the greatest unfinished work in comics (and a real contender for comics’ greatest work of any kind). Don’t let the lack of a conclusion put you off – each volume is self-contained, though there are gains to be had from reading them all, in that characters recur (beyond his usual casting of the Tezuka faces, as if he was a stage manager with a repertory company), as do the central themes of reincarnation and questing for immortality, all centred on the mythical bird of the title, whose blood allegedly confers immortality. There are plenty of other subjects dealt with in the course of it too – Tezuka’s deeply humanistic concerns shine through in all his work, and here he addresses war, social justice, fate and environmental themes, among other things.

Osamu Tezuka’s Phoenix is the greatest unfinished work in comics (and a real contender for comics’ greatest work of any kind). Don’t let the lack of a conclusion put you off – each volume is self-contained, though there are gains to be had from reading them all, in that characters recur (beyond his usual casting of the Tezuka faces, as if he was a stage manager with a repertory company), as do the central themes of reincarnation and questing for immortality, all centred on the mythical bird of the title, whose blood allegedly confers immortality. There are plenty of other subjects dealt with in the course of it too – Tezuka’s deeply humanistic concerns shine through in all his work, and here he addresses war, social justice, fate and environmental themes, among other things.

Tezuka spent 35 years on the series, from 1954 to his death in 1989, producing around 3,500 pages. It comprises twelve books in the English language Viz edition – note that though there are 12 stories, these are not a one-to-one mapping, in that some volumes contain two, and some stories are split over two books, to make the volumes of similar size. The stories zigzag between past and future, seeming to more or less converge towards the present, where we assume the conclusion would have happened. The scope is huge – the first story dates from the origins of Japan as some kind of nation, whereas the second leaps to the end of humanity and countless millions or billions of years beyond, to the evolution of a new intelligent race from slugs, and their end, and another new evolution.

The ambition is equally enormous. I remember reading Jack Kirby’s 2001 series for Marvel, well after the fact. I’d seen that period as the start of his decline into mannered, far less effective work, and I had little interest in something spinning off from what I think is one of the most overrated movies ever, but reading it was revelatory. It’s true that it’s not his best work technically, maybe not his most entertaining, without the astonishing characters that he routinely created across previous decades. But despite all that it’s one of his most interesting pieces of work: 2001 is the work of a veteran creator with a brilliant mind that had perhaps been too centred on entertainment rather than serious art, telling us everything he believes about the world and what it is to be human. Phoenix is the same, except it’s also perhaps Tezuka’s best work in all the other ways too. Also, I think Tezuka was a more interesting thinker, or perhaps it’s just that his humanism and scientific bent (he was a qualified doctor) fits better with my way of thinking than Kirby’s more fantastic and cosmic inclinations.

The ambition is equally enormous. I remember reading Jack Kirby’s 2001 series for Marvel, well after the fact. I’d seen that period as the start of his decline into mannered, far less effective work, and I had little interest in something spinning off from what I think is one of the most overrated movies ever, but reading it was revelatory. It’s true that it’s not his best work technically, maybe not his most entertaining, without the astonishing characters that he routinely created across previous decades. But despite all that it’s one of his most interesting pieces of work: 2001 is the work of a veteran creator with a brilliant mind that had perhaps been too centred on entertainment rather than serious art, telling us everything he believes about the world and what it is to be human. Phoenix is the same, except it’s also perhaps Tezuka’s best work in all the other ways too. Also, I think Tezuka was a more interesting thinker, or perhaps it’s just that his humanism and scientific bent (he was a qualified doctor) fits better with my way of thinking than Kirby’s more fantastic and cosmic inclinations.

And I guess Tezuka’s artistic strategies have always appealed to me enormously. I’m a sucker for anything a bit Postmodern or meta, and while I have no evidence that Tezuka had any interest in Postmodernism as a philosophical or artistic idea, his instincts were to regularly break open his own fictional world, to remind the reader that they are immersed in a comic story created by a specific person. This is partly a case of making explicit something that is generally implicit in Japanese art, something I’ve mentioned on this site before. Storytelling art always has elements of the representational and the presentational: on the one hand, we enter a world and follow a story, a representation of events, albeit fictional ones; on the other hand, we are reading or watching something offered to us by one or more artists, a personal vision, a presentation. Western tendencies, excepting a lot of Postmodern fiction in recent decades, has been more towards the representational: there is a history of striving towards greater realism, naturalism, still a goal in much Modernist work, whether Impressionism in painting or stream of consciousness in prose fiction. Japanese arts did not develop this way, and the balance has always been far more towards seeing things as presentations by artists.

Tezuka makes this explicit: at key moments in stories he will remind us we are reading a comic – and often that we are reading a Tezuka comic – in all sorts of ways. One is his aforementioned use of the same faces in lots of comics, not always in familiar roles, but often with similar personalities – this always puts me in mind of the great screwball comedies of Preston Sturges, where you instantly knew more or less who a character was because he was played by William Demarest or Franklin Pangborn: you were always aware of the actor playing the role. Another tactic is overtly antirealist moments. One story set nearly a thousand years ago features a great Buddhist monk. We are told that he had countless followers and that his writings were read widely; and then that he was a frequent guest on TV game shows, and we see him behind a podium pressing a big button. Key events in the 12th Century Heike Wars segment of the story turn on a telephone call. He will often undermine any sense of realism at the most tense and important moments.

Tezuka makes this explicit: at key moments in stories he will remind us we are reading a comic – and often that we are reading a Tezuka comic – in all sorts of ways. One is his aforementioned use of the same faces in lots of comics, not always in familiar roles, but often with similar personalities – this always puts me in mind of the great screwball comedies of Preston Sturges, where you instantly knew more or less who a character was because he was played by William Demarest or Franklin Pangborn: you were always aware of the actor playing the role. Another tactic is overtly antirealist moments. One story set nearly a thousand years ago features a great Buddhist monk. We are told that he had countless followers and that his writings were read widely; and then that he was a frequent guest on TV game shows, and we see him behind a podium pressing a big button. Key events in the 12th Century Heike Wars segment of the story turn on a telephone call. He will often undermine any sense of realism at the most tense and important moments.

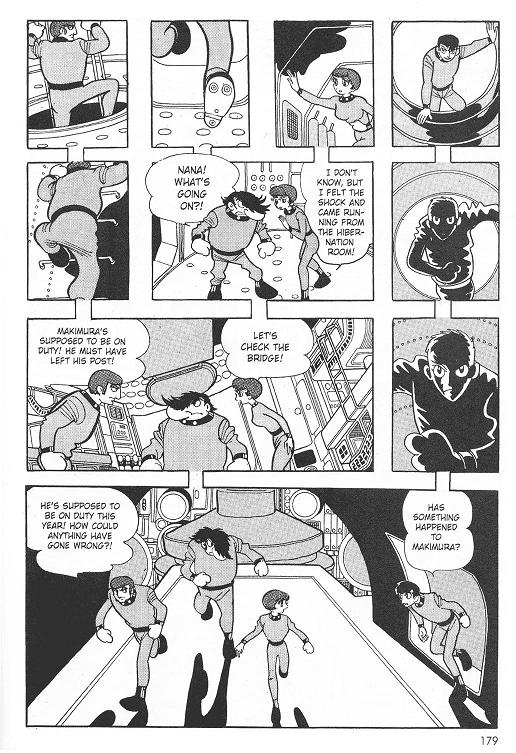

Not everyone will like these unusual storytelling strategies, but I am sure any comic fan would find an enormous amount to admire and be impressed by in the art of these comics. There is plenty of artistic experimentation here, in every story, too many instances to try to summarise of trying different ways of telling a story. There are lengthy sequences shown as if on a stage. There are sequences where the pages are split between characters, merging in unexpected ways when any meet, including a sequence of pages where a quarter is black, after one of the four dies. It’s full of stunning and beautiful pages and panels of an almost inconceivable variety, all delivered by one of the great cartoonists of world comics.

All of this is high praise, but I need to mention that these stories are tremendously enjoyable to read, even if you have no interest in comics as art (which I don’t suppose is the case for many readers of a site like this). The stories are exciting and lively, full of action and incident and ideas, great entertainments. I wouldn’t wish my high art claims to obscure this fact, as it sometimes does with foreign movies, for instance – my favourite film, Seven Samurai, is an art film in the West, but it was a giant summer blockbuster action movie in Japan. It’s important to remember that great art and great entertainment can go seamlessly together.

A comics expert in Japan was once asked why comics were so huge in Japan compared to everywhere else in the world. “Japan had Osamu Tezuka, whereas other nations did not,” was the simple answer offered. Yes, that is far too simple, but his importance to the style and success of manga (and indeed Japanese animation) can hardly be overstated, and if I were to recommend just one of his many, many works (he produced over 150,000 pages in his career), it would be this one, since it shows his artistic greatness, his consistent ability to entertain, and the breadth of his vision and ideas. It might even be my nomination for the greatest work in the history of comic books. I’m sure you can at least find one of these (there is no real need to read them in order) from a local library, and I urge anyone who hasn’t tried the series to at least give it a go.

Tags: Manga, Osamu Tezuka, Phoenix

“I’m a sucker for anything a bit Postmodern or meta, and while I have no evidence that Tezuka had any interest in Postmodernism as a philosophical or artistic idea, his instincts were to regularly break open his own fictional world, to remind the reader that they are immersed in a comic story created by a specific person.”

Cough, splutter! Surely here you are confusing postmodernism (a philosophical position) with metafiction (a literary conceit). An artwork can be one without the other, and of course metafiction predates postmodernism by hundreds of years.

I shan’t start here all over again about my opinions on the risible world of postmodernism…

I don’t think I am confusing them at all! I use ‘or’ for a start, but also metafiction has been a major part of PoMo writing, and these days is largely seen as part of it.

This is rather like saying anything painted in blue must have been done by Picasso.

Unless you’re arguing Tesuka actually invented postmodernism in 1954…

I think if we claim that ONLY brand new ideas can count as being part of Postmodernism then we eliminate nearly everything from it! This is an absurd position to take. I prefer to retrospectively dub Tristram Shandy, say, as ProtoPoMo!

Also, Postmodernism was invented by Marcel Duchamp with his first readymade.

“I think if we claim that ONLY brand new ideas can count as being part of Postmodernism then we eliminate nearly everything from it!”

But still not quite enough!

If everything that features metafiction is held to be PoMo then a whole bunch of stuff, including much of Shakespeare suddenly becomes PoMo – centuries before we even had modernism!

Metafiction is when an artwork draws attention to it’s own formal qualities. Postmodernism was a philosophical stance which was ultimately about reality and ultimately was against it. It asserted that there were no meaningful or causal relations in reality save the ones we subjectively imposed on it.

I don’t agree that Duchamp’s readymades were postmodernist (tho’ they most likley fed into it), but that’s not really germane to the argument.

Anyway, I did enjoy the rest of this article, even if I’m harping on about this one point!