Lone Wolf & Cub

by Martin Skidmore 28-Nov-10

This epic series is, for me, one of the greatest achievements in comics. It tells the story of Itto Ogami, who starts as the official executioner for the Shogun. The rival Yagyu clan, who had wanted that high position for themselves, attack his family and leave fake evidence to discredit him. He leaves to walk meifumado, the “road to hell”: to work as a hired assassin in an attempt to amass sufficient resources for revenge.

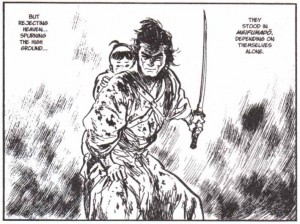

This epic series is, for me, one of the greatest achievements in comics. Its 8,700+ pages (over three times as long as Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four run, in about half the time) tell the story of Itto Ogami, who starts as the official executioner for the Shogun, Japan’s samurai ruler, in Edo period (1600-1868) Japan. The rival Yagyu clan, who had wanted that high position for themselves, attack his family and leave fake evidence to discredit him. He leaves to walk meifumado, the “road to hell”: to work as a hired assassin in an attempt to amass sufficient resources for revenge.

This epic series is, for me, one of the greatest achievements in comics. Its 8,700+ pages (over three times as long as Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four run, in about half the time) tell the story of Itto Ogami, who starts as the official executioner for the Shogun, Japan’s samurai ruler, in Edo period (1600-1868) Japan. The rival Yagyu clan, who had wanted that high position for themselves, attack his family and leave fake evidence to discredit him. He leaves to walk meifumado, the “road to hell”: to work as a hired assassin in an attempt to amass sufficient resources for revenge.

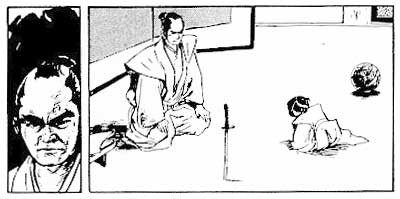

But there is one survivor of the attack on his family: his baby son. He doesn’t know the soul of this child, and devises a way to find out. He places a brightly-coloured ball to one side, and drives his sword into the matting on the other side. If Daigoro goes to the ball, he lacks the warrior soul, and Itto will kill him; if he chooses the sword, the boy will accompany his father on their grim path. The title of course gives away what the decision was.

I love everything about this series. Kazuo Koike is one of Japan’s great writers of comics, and part of the appeal for me is his detailed and accurate knowledge of the country’s history, and fortunately for me, Edo Japan is the single time and place that I find most interesting in all the world. It was a society like no other, with all kinds of unique and extraordinary qualities and rules. Unfortunately, much the most extreme embodiment of this was in Edo itself (now called Tokyo), and the nature of this story does keep Itto out of the capital almost all the time. Nonetheless, my interest in the period is all but unlimited, and Koike not only captures the time accurately, he gives us all sorts of appealing small details – I am particularly fond of a scene showing how prospective maids were auditioned. He’s renowned in Japan for his research and accuracy (which shines through even more in a series like Path of the Assassin, which may well come up in this manga series at some point), and he uses it superbly.

I love everything about this series. Kazuo Koike is one of Japan’s great writers of comics, and part of the appeal for me is his detailed and accurate knowledge of the country’s history, and fortunately for me, Edo Japan is the single time and place that I find most interesting in all the world. It was a society like no other, with all kinds of unique and extraordinary qualities and rules. Unfortunately, much the most extreme embodiment of this was in Edo itself (now called Tokyo), and the nature of this story does keep Itto out of the capital almost all the time. Nonetheless, my interest in the period is all but unlimited, and Koike not only captures the time accurately, he gives us all sorts of appealing small details – I am particularly fond of a scene showing how prospective maids were auditioned. He’s renowned in Japan for his research and accuracy (which shines through even more in a series like Path of the Assassin, which may well come up in this manga series at some point), and he uses it superbly.

The art is every bit as good. Goseki Kojima (a nice coincidence is that he was born on the same day as Osamu Tezuka), for me, is one of the most powerful and exciting artists in the history of comics. It’s worth noting that he was also extremely fast. We’re in an era where Western comic artists often struggle to produce a whole 24-page comic a month. Decades ago, the fastest might have been three times that speed, pencils only. Kojima’s pace on Lone Wolf & Cub alone was more than double that, and he did a lot of other work in parallel. I’m not sure how much assistance he had, if any, but bar the occasional detailing of a building or the like, it all looks to me like the work of a single hand, so my guess is that any assistance was at a very juniour level.

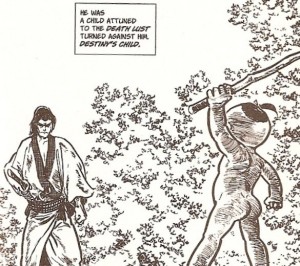

There are beautiful landscapes, and highly kinetic action scenes inked with a rough vigour similar to that of Joe Kubert, but for me the key to the series is the people, and his work on them is magnificent. Koike gives him a number of requests that I would have imagined were close to impossible. Daigoro is aged three for the bulk of the story. In one episode, he is separated from his father, and at one point he is naked and burnt, and confronted by a samurai, sword out. Daigoro picks up a stick and takes up a battle pose, and the samurai, meeting his eyes, recoils in shock and fear. The challenge of portraying a three year old who can evoke that reaction is huge, but Kojima rises to the occasion brilliantly: the close-up on Daigoro’s eyes may be the single panel in comics history that I have spent most time looking at.

There are beautiful landscapes, and highly kinetic action scenes inked with a rough vigour similar to that of Joe Kubert, but for me the key to the series is the people, and his work on them is magnificent. Koike gives him a number of requests that I would have imagined were close to impossible. Daigoro is aged three for the bulk of the story. In one episode, he is separated from his father, and at one point he is naked and burnt, and confronted by a samurai, sword out. Daigoro picks up a stick and takes up a battle pose, and the samurai, meeting his eyes, recoils in shock and fear. The challenge of portraying a three year old who can evoke that reaction is huge, but Kojima rises to the occasion brilliantly: the close-up on Daigoro’s eyes may be the single panel in comics history that I have spent most time looking at.

This is what gives an episodic samurai action-adventure story an entirely original concept, and the bizarre way that Daigoro has grown up is central to some of the most memorable moments in the whole series. In one tale, Itto is fighting a woman in a snowy setting. Daigoro falls through ice into a pond, and is in obvious danger of drowning. The woman offers to wait while Itto saves his son, but he is above everything else an assassin, doing his job, so he declines. She looks shocked, and after a moment she moves to rescue Daigoro, extending a branch for him to grab. Because his father is not choosing to act, Daigoro declines the branch, and the fight resumes as he struggles to save himself.

This exceptionally alien mentality goes beyond the astonishing boy. Itto Ogami is commissioned to kill a revered priest, considered by many to be a buddha. He attacks, but cannot strike, and the priest explains that Itto’s spirit is insufficiently committed to his path, that he has not achieved true enlightenment, meaning he cannot kill him. He goes away to meditate alone for days (he often leaves Daigoro on his own), then attacks again, this time succeeding, and the buddha praises his enlightenment with his dying words.

Mortality is a tricky issue in Japanese narrative art, for various reasons, and this incident demonstrates that. I think the core reason lies in a different attitude to art. You can see a story, in any form, as part representation, a depiction of a real world or a fictional one we are to believe in, and as part presentation, a creative vision offered by one or more artists. The search for realism in Western arts, the high valuing of this goal, has typically tipped our readings substantially towards representation, but Japan has shown very little interest in realism over the centuries, seeing art as far more presentations by artists. This can mean that Japanese audiences are less inclined to try to identify with the characters, and can see stories less as depictions of the world, and therefore read less moral messages into them. Arguably their religion, a strange blend of the animist Shinto and Hindu-derived Buddhism, may be a factor too. The long upper-class dominance by Zen, a religion where moral rules are a minor aspect, combined with ancestor and animist spirit worship with almost no moral rules at all, is in stark contrast to the Judeo-Christian background the West generally shares.

This can be seen in countless gangster movies, where morality is hardly a factor at all, and this amorality is also evident in Lone Wolf and Cub. This and the strangeness of the spirit of the lead pair of characters can strike Western readers in different ways. I am sure some find it distasteful and alien, and cannot connect with it, but for me this series was a big part in sparking a broader interest in Japan and the different ways its arts work – some will know of my other site, all about Japanese arts. There was one other way LW&C fed into this: I realised that reading this was an extremely similar experience to watching the samurai movies of Akira Kurosawa, and since he was and is my favourite movie director, this connection suggested there was something in the Japanese psyche and/or aesthetic that I loved that may extend beyond individual creators.

This can be seen in countless gangster movies, where morality is hardly a factor at all, and this amorality is also evident in Lone Wolf and Cub. This and the strangeness of the spirit of the lead pair of characters can strike Western readers in different ways. I am sure some find it distasteful and alien, and cannot connect with it, but for me this series was a big part in sparking a broader interest in Japan and the different ways its arts work – some will know of my other site, all about Japanese arts. There was one other way LW&C fed into this: I realised that reading this was an extremely similar experience to watching the samurai movies of Akira Kurosawa, and since he was and is my favourite movie director, this connection suggested there was something in the Japanese psyche and/or aesthetic that I loved that may extend beyond individual creators.

You can get away with reading most of LW&C in any order. Most of the stories are self-contained episodes, though the attempts of the Yagyu clan to kill him are a regularly recurring strand. The one exception is the last handful of volumes, where they take well over 1,000 pages building to the superb climax – these will lose a lot if not read in order, and they gain a lot by being the finale of an epic mission.

Dark Horse announced that they would be publishing the sequel, by Koike and artist Hideki Mori. I’m reluctant to offer any story details, since it gives at least one spoiler about the ending of the original series; and in any case, that announcement was a few years back, and we’ve seen no sign of it, dammit.

Tags: goseki kojima, kazuo koike, lone wolf & cub, Manga

There’s so many things to love about this series – the facial expressions, the landscapes, the drawn out pacing, the strangeness of the cultural perspectives. I don’t know if I’d ever want to read the sequel. Like most highly-anticipated events, it’d probably come as a huge letdown.

Yes, every chance it would disappoint, but Koike is such a great writer (he’d make my top three or four non-artist comic writers) that I’d still very much like the chance.

What does the name Daigoro mean in the series of Lone Wolf with Child. The father picks the name with an explanation of it in one of the TV episodes.

Sadly, Martin is no longer around to answer this question. Any reader able to answer Stan?

I’m sorry to hear about Martin, even though this post is the first time I ever heard of him and the first time I ever visited this site.

In the series, Itto says, upon naming his son: “Daigoro – emotions of human beings. Whatever he is confronted with, he shall not be selfish nor arrogant. He will live boldly and just. He will keep life and death on his mind and live through. Daigoro will lead to great enlightenment. I wish for him to live strong as a human being.”

I haven’t read the original manga (shame on me), yet. This is the translation from the subtitles.

From other posts on the net, I gather that the name Daigoro refers to the number five (son number five, for instance). There are five fingers on each hand, and there are five elements (earth, wind, air, water, void).

I have no way of verifying this myself, but if the information is correct, I think it is a very poetic name considering Daigoros path (which, as readers/viewers of the series/film will know, he chooses himself). Thus, he carries in his name the secret, the tools, the wisdom, the reminder of what will keep him afloat in the daunting tests that lie ahead of him.