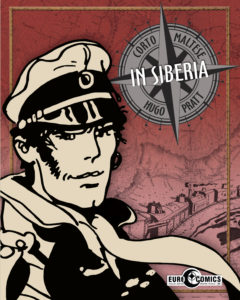

Corto Maltese: In Siberia

by Frank Plowright 06-Apr-17

While Pratt is justifiably acclaimed for the looseness of his illustration, evident on any page, when it comes to trains that is discarded, as Pratt strives for mechanical exactitude. Every bolt and every rivet is included, and these are magnificent looking beasts, the central spectacle being a battle between them, surely still unique for comics.

In 1974, when Hugo Pratt began serialising what would become Corto Maltese in Siberia, he’d been producing the feature for eight years, and six collected editions of his mysterious adventurer were in print. These feature separate shorter stories connected by a common location, with characters occasionally recurring.

In 1974, when Hugo Pratt began serialising what would become Corto Maltese in Siberia, he’d been producing the feature for eight years, and six collected editions of his mysterious adventurer were in print. These feature separate shorter stories connected by a common location, with characters occasionally recurring.

Siberia eventually dispenses with that format as Pratt confidently strides into full length narratives, but this appears to have been a later decision, as, although it sets the plot in motion, the opening chapter is very much its own beast. It takes place in Hong Kong, opens with a dream sequence, and only in the final pages concerns itself with the book’s greater plot.

Corto managed to absent himself from World War I, but becomes involved in the now often forgotten sequel, when many of those who’d quelled the German Kaiser’s ambition moved East to combat the Russian Revolution. Anti-Communist forces rallied behind Admiral Kolchak, operating from Siberia having come into possession of a significant portion of Russia’s gold reserves, which he held aboard a well-guarded train. Assorted parties have their eyes on it, and Corto’s involvement comes via a Chinese organisation, whose expedition he’s to lead, to take the gold as the train approaches the Mongolian border.

In Hong Kong and China, Corto renews old acquaintances and makes new ones, some more reluctantly than others, as Pratt immerses us in Corto’s contradictory ways, such as they’re revealed. He remains an enigma, sometimes needlessly provocative, sometimes diplomatically silent, a pause serving as a statement, yet honesty often the best policy when confronted with danger. He’s certainly motivated by money, yet it’s disclosed he has enough to fund a base he rarely visits. He’s predominantly fatalistic and seemingly lacking compassion, yet places immense faith in love and is accepting of the inexplicable.

Among the supporting cast, Rasputin returns, but Pratt’s borrowed the name and appearance rather than appropriating the historical character. More so than with previous books, however, Pratt constructs his story around real people. The period shortly after the Russian Revolution was populated by several opportunistic maverick empire builders, all anti-Communist, and Pratt’s depiction of them is glorious. Baron Ungern-Sternberg believed he could restore the Mongolian empire, and is portrayed as emaciated and foul-tempered, while Cossack General Semetov is a sybarite ensconced in his mighty armoured train.

Among the supporting cast, Rasputin returns, but Pratt’s borrowed the name and appearance rather than appropriating the historical character. More so than with previous books, however, Pratt constructs his story around real people. The period shortly after the Russian Revolution was populated by several opportunistic maverick empire builders, all anti-Communist, and Pratt’s depiction of them is glorious. Baron Ungern-Sternberg believed he could restore the Mongolian empire, and is portrayed as emaciated and foul-tempered, while Cossack General Semetov is a sybarite ensconced in his mighty armoured train.

While Pratt is justifiably acclaimed for the looseness of his illustration, evident on any page, when it comes to trains that is discarded, as Pratt strives for mechanical exactitude. Every bolt and every rivet is included, and these are magnificent looking beasts, the central spectacle being a battle between them, surely still unique for comics. Pratt’s not above re-using some train illustrations, but hell, he’s put the effort in, and that’s hardly the central issue of this glorious historical adventure. That’s the constantly morphing allegiances where power and gold are concerned.

Pratt doesn’t use thought balloons or narrative captions, and this adds immensely to the elusive nature of the story. We never really know what anyone is thinking, and what they say isn’t necessarily true, so everything must be deduced from actions. Corto’s use to various parties, and his use for them, changes throughout a brilliantly conceived adventure, where the reader can never be certain of whether anyone’s telling the truth.

As the form has become more accepted, and boundaries have been stretched, many early graphic novels no longer impress as previously. That’s not the case for Corto Malteste in Siberia, whose confident historical fiction is rarely equalled, never mind bettered.

The ending is novel and brilliant, calling on the testimonies of witnesses as if in court proceedings.

Tags: Corto Maltese, Corto Maltese in Siberia, Hugo Pratt

SIBERIA is also the last of the more realistic, adventure-strip half of Corto. From VENICE onward, the more dreamlike, magic-realist half of Corto begins.

– “Siberia eventually dispenses with that format”

SALT SEA (1967–1969), Corto’s first graphic novel, was more critically acclaimed than commercially viable. Pratt was given the opportunity to carry on if he would parcel out his stories as standalone 20-pagers for comics mags, hence the short-story collections that followed. They let the series become successful enough to resume the graphic novel format with SIBERIA.

– “Pratt is justifiably acclaimed for the looseness of his illustration”

Yes. Pratt comes from Roy Crane and Noel Sickles by way of Milton Caniff and Alberto Breccia, and he influenced Frank Miller, Muñoz, Manara, Comès, Tardi, Forest, F’murrr, Baru, Rickheit, Graham, etc., in the same way that Barron Storey influenced Sienkiewicz, McKean, Mack, Wood, Templesmith, etc.

– “when it comes to trains […] Pratt strives for mechanical exactitude”

Sorry, those bits are drawn by Guido Fuga. (Uncredited, as with Hergé’s or Tezuka’s assistants.)

Pratt had this friend who had fallen on hard times. On SIBERIA and most following books, he hired him to draw mechanical parts such as trains, planes, cars, guns, etc. (In VENICE, he also let him try his hand at a few backgrounds.) Fuga’s pen style didn’t really mesh with Pratt’s brushes, but life and friendship were more important than work and art to him.