The Year of Loving Dangerously: A Graphic Memoir

Reviewed by Nevs Coleman 21-May-12

What sets this apart from a lot of other autobiog work, and in fact elevates it to that higher standard set by Spiegelman, Pekar, Spain, Crumb, etc., is that Ted Rall’s neither looking for sympathy nor approval in this work. He’s fully cognisant of the fact that it’s his choices that has put him in the position that he’s in.

A Brief History Of Manipulation

A Brief History Of Manipulation

(With Apologies to Henry Rollins’s “Black Coffee Blues” and Amy Hempel.)

“She kicked the glass through the door and stepped in. I was terrified.”

“I called out as my friend began to pass out, she was turning blue, and the hole in her arm was starting to ooze. I thought Gaye would die. maybe the stuff had been cut with shit as a revenge ploy for Gaye stealing Gyda’s man last summer. Gyda seemed fine with losing Richard but then she did make it look like she slept with a noted sci-fi writer in front of her ex before Tim just to piss that guy off. I looked up and saw Patti trying to get the door open. She kicked the glass through and stepped in. I was terrified. Gaye had stopped breathing.”

Funny how the details you drop in and out of a story can change the context of the excerpt entirely. Let me elaborate:

– She goes up to him and tell him she hated the Black Panther comic. She revels in his disgust at her shameless racism. Later, she is constipated. He places a boom box outside the toilet and plays It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back! by Public Enemy loudly. He laughs at the thought of her shit jammed inside her while angry black men shout. Until now, she didn’t know for sure it was him.

– We hug late in the night watching Downton Abbey and singing Amanda Palmer songs. Later, she is in a mental hospital. I make excuses not to visit her. I can’t be bothered with crazy people anymore.

– He gave his first blowjob when he was twelve to his Daddy. It was their little secret. Later he would become a prostitute to pay for college.

– “You can’t review my indie records,” I shout at her, down the pub. “You don’t like indie records!” “No,” she laughs, “I don’t like your indie records. There’s a difference.” She goes to the toilet. Before she comes back, I skulk off into the night. It’s what I do when I hear things I don’t like. So far it’s worked pretty well.

– “She’s been going out with John for a couple of … years. She didn’t want you to know. You did know, right?'” “She’s my best friend, of course I knew, I was respecting her privacy by not bringing it up.” The second statement I made wasn’t true. Eventually, the first one wouldn’t be, either.

– She’s that girl. She’s there to swoop in when they break up from long-term relationships. The men who just need to feel loved. She is always single. She can do whatever she wants. She’s happy to let them think she can be changed. Done. Done. Done and she’s onto the next one.

All of the above is true. In every instance, I’ve changed the pronouns. Some of them are just things people have told me about. Others are events in my life I’ve mucked about with. I’ve also missed out certain details because it serves my point to invoke certain reactions in you. The problem with writing about real people is that neither people nor even memory can be trusted all the time to be totally objective.

Given that we live in a world where people seem to believe that films like Braveheart, What’s Love Got To Do With It?, 300 and The Patriot are essentially documentaries, then being the last person who gets to say ‘This is what happened!’ carries with it a certain moral responsibility to get both sides of the story in, I’d imagine. Which is doubly tricky since not every one is a writer or artist. Or particularly wants their life turned into ‘art’. (I certainly don’t.)

Heck, just ask Roseanne Cash, who’s more than slightly annoyed that the world now thinks that her mother is the woman portrayed in the film Walk The Line. I’d be willing to bet that maybe there’s more to the history of Nico and Jim Morrison’s relationship than what’s told to us by the filmThe Doors. All I really know about it is what other people (music journalists, film makers, etc.) have told me. I can’t verify my impression of it for myself, cause, well, they’re both dead. That’s it.

So, given my belief that most of the content of autobiographical comics (and most other fiction) is an exercise in banality and bullshit, and my little adventure into living rough for six months, my hilarious editor for this site gave me a copy of The Year Of Loving Dangerously to review. He didn’t actually burst out laughing as he handed me the book. Which was good of him.

Published by NBM, The Year Of Loving Dangerously covers 1984 for Ted Rall. After being expelled from college due to a random injury from a wart and some rather unsympathetic university dorm officials, Ted ends up moving his stuff into storage and then he’s out on the street with eight dollars and then he’s on his own with nothing but his wits to keep him from starvation and sleeping rough. The minutes of self-torture, guilt and fear as he rings that person in hope that they can come through with the cash he needs just to get through the day. The moments where he’s trapped between the humiliation of asking his mother for his cash and his knowledge that if he doesn’t, he may not eat, are painful reading indeed for anyone who’s been in that situation.

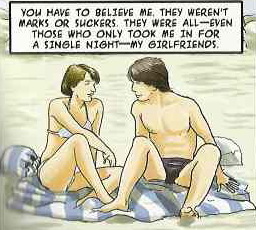

Soon he finds, much to his surprise, that he’s very good at chatting up women. This creates an unexpected survival aide, but one not without its own form of neurosis and self-hatred quickly creeping in.

“I needed a bed. To get one, I needed to be charming and funny and giving. Would I have fucked Melissa three times before going to sleep had I not wanted her to consider inviting me back? … On the other hand, I didn’t have much of a choice. Because I needed her. It was impossible to assess whether I actually liked her. … Essentially, I was a rent boy. I had sex for shelter, clean sheets and, if I got lucky, food.”

Eventually, the reality and pressure becomes too much for Ted. He finds himself on the roof of a building, realising his situation is simply more than he can bear. People become righteous when they condemn the suicidal. All being suicidal means is that you have run out of strength, hope or will to deal with the way your existence is. Even if the anguish is self-inflicted, all you really want is an end to your pain. He stands there, urging himself to take the last step and finish it.

“Jump, damn you. Jump!”

But he can’t do it, with tears in his eyes, he turns away from the ledge.

“Fucking Pussy…”

From there, the rest of the book is Ted’s decision to put his life together. It isn’t easy, by any means, but obviously it isn’t a spoiler to say that Ted survives as he’s turning out fine work that can be viewed here. What sets this apart from a lot of other autobiog work, and in fact elevates it to that higher standard set by Spiegelman, Pekar, Spain, Crumb, etc., is that Rall’s neither looking for sympathy nor approval in this work. He’s fully cognisant of the fact that it’s his choices that has put him in the position that he’s in. He’s quite aware that you might not like who he is in the book, but he’s damn honest about it in his “Foreword”:

“Year is something of a reaction against the pathetic archetype that defines so many other cartoonist’s personal narratives, in which guys – most of whom, are actually reasonably attractive and charming – declaim their masturbatory nerddom to an uncaring world. (Which does actually care enough to buy their books and adapt them to Major Motion Pictures.)”

Oh, and it’s all juxtaposed beautifully with the clean sheen on Pablo G. Callejo’s art. It exudes the 1980s from mullets and turn-ups. I could hear Spandau Ballet and A-ha playing in the background; my only real problem was that his depiction of The Dead Kennedys’ gig was incredibly calm. That, and Ted never seemed to sleep with anyone unattractive. All of Pablo’s women are beautiful, and I’m willing to bet there’s a few … encounters that Ted wouldn’t want to recollect.

Ted’s one of the lucky ones. He had people who cared for him enough that he made it through to the other side. I’m one of them too, as I’m well enough to be writing this from the comfort of my girlfriend’s bedroom. We were both blessed. All it would have taken was the wrong thing to happen and it would have been over. With that in mind, I dedicate this review to Will, Clare, Dan, Sarah, Howard, Jon, Sara, Anna, Kayleigh, Zara, Dale, Ceri, Ruby and ScaryBoots.

It’s too easy to judge what you don’t know fully. Never forget that.

Tags: Pablo G. Callejo, Ted Rall

I love this art….I never saw the comic in any US comic shops….I guess I may have to order it to get a copy from NBM. Does anyone else think that the shot with the heart visible on his chest is an homage to Frida Kahlo?