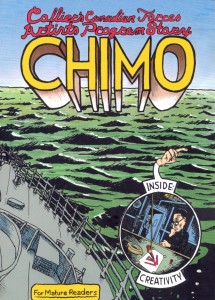

Chimo

Reviewed by Andrew Moreton 14-Sep-11

He wears his artistic influences on his sleeve, Crumb being far and away the most pronounced. This manifests in a familiar first person delivery and copious cross-hatching, but instead of the confessional canon of the Crumb copiers Collier produces what he calls “comic strip essays” – usually self-narrated documentaries where the author’s reflections and musings are woven into and around a true story.

Canada’s always seemed like a lesson in How To Do Things Nicely in North America. Sitting up there in the cold and being all Swedish-social-policy and asylum friendly, it’s managed to project an image as a liberal bastion on the top edge of a US that’s been bolstered by the relentless export of culture funded by the Canadian government.

Canada’s always seemed like a lesson in How To Do Things Nicely in North America. Sitting up there in the cold and being all Swedish-social-policy and asylum friendly, it’s managed to project an image as a liberal bastion on the top edge of a US that’s been bolstered by the relentless export of culture funded by the Canadian government.

Though the political realities of modern Canada (tar sands drilling, electing Stephen Harper, building super prisons) could break a pinko’s heart, The Canadian Council for the Arts is still funding projects as if the country’s not being run by Conservative maniacs. Recent books that have been sponsored by this august body include Zach Worton’s The Klondike, Chester Brown’s Paying For It, and, under scrutiny here, David Collier’s Chimo.

Collier’s been drawing comics for a long time now, in fact it’s been nearly 25 years since he first appeared in Weirdo, and, while he’s not made the impact of some of his more conspicuous Canuck compatriots, nevertheless, he’s weathered the comparative lack of attention and produced a solid body of work.

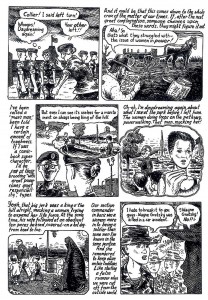

He wears his artistic influences on his sleeve, Crumb being far and away the most pronounced. This manifests in a familiar first person delivery and copious cross-hatching, but instead of the confessional canon of the Crumb copiers, Collier produces what he calls “comic strip essays” – usually self-narrated documentaries where the author’s reflections and musings are woven into and around a true story.

He wears his artistic influences on his sleeve, Crumb being far and away the most pronounced. This manifests in a familiar first person delivery and copious cross-hatching, but instead of the confessional canon of the Crumb copiers, Collier produces what he calls “comic strip essays” – usually self-narrated documentaries where the author’s reflections and musings are woven into and around a true story.

While there’s an element of self-confession to this, Collier doesn’t dwell on the personal mortification and sexual mores that have become associated with this kind of thing – he’s more interested in the external world than your average auto-bio auteur and has far less of an underground sensibility.

How far from the underground is underlined by his latest offering, Chimo, a memoir in which Collier describes and riffs on his decision to rejoin the Canadian army at the age of 40. This seems a surprising life decision from a liberal artist, but David Collier’s take on armed service is an unusual and responsible one. He’d spent three years in the army back in the early 90’s (some of his first strips published were set in barracks) and had left to pursue more artistic endeavors.

His years in the Army left Collier with the perception that, in the Canadian Army at least, “all this indoctrination [created] … “a moral compass pointing in a different direction than the other(s)”. Army life seemed to have worked well for him and the habits of discipline and training had stood him in good stead, as well as provided rich sources of inspiration for his art. So, unusually for comics artists of his pedigree, he feels an affinity and even duty toward the military and the idea of a kind of civic military service.

This makes for a fascinating “comic strip essay” told from an unusual angle. A few years after Canada joined the war in Afghanistan, Collier joined the Canadian Forces Artists Program, and after a few assignments to training camps and other non-combat zones, realised that if he re-enlisted as an Army Reservist he would maybe sent on more interesting and challenging assignments (he was thinking of Afganistan).

The comic tells the story of his re-enlistment process and the difficulties facing even a fit forty year old in keeping up with recruits half his age. On the way we cover a lot of ground – Collier’s early army career, the history of Canadian war art, mediations on exercise, digressions on sportsmen and skiing and musings on mortality – he’s not afraid to pack in the detail.

Looking back through the book it becomes apparent that the discursive and diverted nature of the storytelling doesn’t always work to the best effect – threads of thought are sometimes dropped, never to return – but on first reading the essay is thought provoking, entertaining and an unusual take on military life.