Carla Speed McNeil

by Jenni Scott 16-Jan-11

Carla Speed McNeil, creator of Finder and artist on various other comics, in interview.

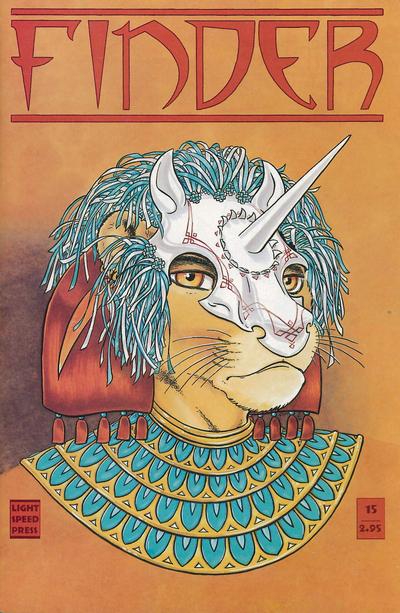

For several years, self-confessed obsessive Carla Speed McNeil, under the imprint of Lightspeed Press, produced

For several years, self-confessed obsessive Carla Speed McNeil, under the imprint of Lightspeed Press, produced

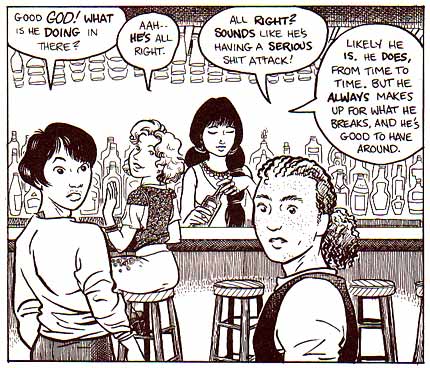

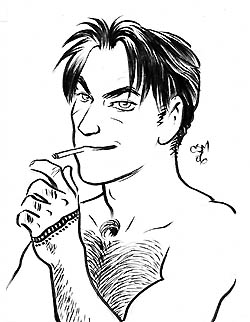

Finder, a series which delighted and fascinated readers with its combination of intricate and meticulously-imagined worldscape, a mastery of body language and facial expression unparalleled in the field, and the hottest leading man in funnybooks. In August 2003, Carla was the guest of honour at Oxford’s independent comics convention, Caption, where she was interviewed by Jenni Scott and an enthusiastically participating audience…

Jenni Scott: This is a very exciting year for Caption; this is Carla’s first trip to a European convention – or to Europe – and we’re delighted to have her here, particularly, because the Caption committee loves her comic Finder, and hope to spread the word about the series.

Carla, for those who haven’t yet come across Finder, what is it, what’s it all about?

Carla Speed McNeil: Well, I’ve never been able to come up with a good, high-concept, ‘ten words or less’ description; I like to use an old term from 1930’s science-fiction, they called it ‘aboriginal sci-fi’; I’ve never had the math or the science to do the ‘hard’ SF, the rocketships and ray-guns thing. But the side of science-fiction that derives from the softer sciences like anthropology, even psychology, stories taken from that were called ‘aboriginal’ sci-fi, about weird alien cultures, and Finder’s one of those.

Carla Speed McNeil: Well, I’ve never been able to come up with a good, high-concept, ‘ten words or less’ description; I like to use an old term from 1930’s science-fiction, they called it ‘aboriginal sci-fi’; I’ve never had the math or the science to do the ‘hard’ SF, the rocketships and ray-guns thing. But the side of science-fiction that derives from the softer sciences like anthropology, even psychology, stories taken from that were called ‘aboriginal’ sci-fi, about weird alien cultures, and Finder’s one of those.

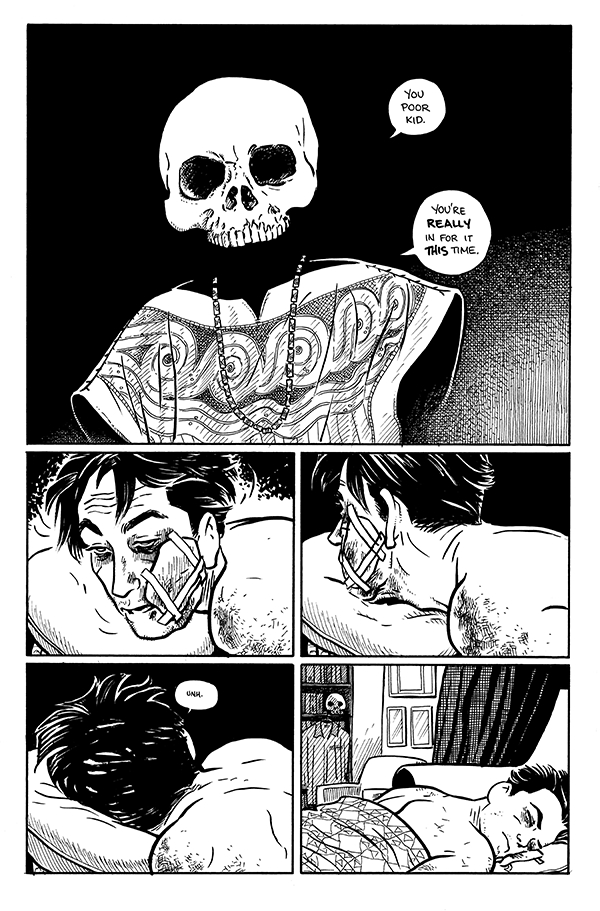

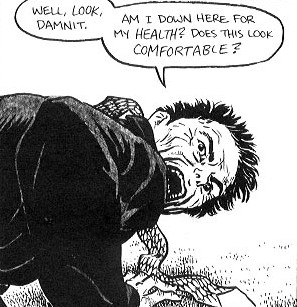

The main character, Jaeger, he’s like an aboriginal detective, he really doesn’t have any concept of what it means to mind your own business, he thinks he does, but he just wanders into town like Clint Eastwood and gets himself into another mess.

A lot of the stories are in the science-fiction milieu but still fairly true-crimeish, really, but I’ve deviated from that enough times to probably lose half my readership! (laughs). But people seem to stick with me…

The thing I’ve done that I would admit to being proud of, which was a departure and which I had to struggle to keep science-fiction elements in, was a story called Talisman, which circled around a really small girl from the first story, who was given a book by the main character which she was too young to read, and she became obsessed with the story in it, which was so fascinating, and then he left, which he does from time to time, and she couldn’t read it any more! She’d ask other family members or friends to read it to her, and they “read it wrong”. Then her mother threw it out, as mothers tend to do, and she spends her whole life trying to recreate the story that she loved. Well, if I keep yapping about the plot, there goes what little suspense I’ve managed to create, so…

I based it partly on what I used to do to one of my little nieces; you know how a kid will bring you the Same. Book. Every. Night. and they just never get tired of it? After about the third night,

I got bored and I just started making things up. She’d sit on my lap, and flip the pages whenever she felt like it, and the story never ended, so she was blissfully happy whenever I was available to read the book, and she’d get mad at other people because they didn’t read the book the way I did; I lived in terror of her learning to read, and finding out I’d just been yankin’ her chain all these years! She’s nine now, and doesn’t remember any of this, so I’m off the hook!

Jenni: So was this actually before you started doing comics? Or have you been doing comics all along but only started publishing Finder relatively recently?

Carla: I have a good friend who also acts as my roadie at the one or two cons that I don’t have to fly to, and he’s been my sounding board for the last eight years or so. I just had my sweat-stained sketchbook when I met him, and he just kept saying, “This is interesting, draw me another one”. Over and over, and after about six months of this I resolved to sit down and draw everything that had been mulched away in my head, and after about a year I had this stack of pages full of the kind of meticulous notes that are only enjoyable if you’ve already gotten into a story. Characters, timelines, places, people, things, and I looked at it and felt kind of disgusted, because I still didn’t have any clue how to start writing a story!

Carla: I have a good friend who also acts as my roadie at the one or two cons that I don’t have to fly to, and he’s been my sounding board for the last eight years or so. I just had my sweat-stained sketchbook when I met him, and he just kept saying, “This is interesting, draw me another one”. Over and over, and after about six months of this I resolved to sit down and draw everything that had been mulched away in my head, and after about a year I had this stack of pages full of the kind of meticulous notes that are only enjoyable if you’ve already gotten into a story. Characters, timelines, places, people, things, and I looked at it and felt kind of disgusted, because I still didn’t have any clue how to start writing a story!

So essentially I just grabbed every character that was in the right place at the right time, and said, “The hell with it, I’ll never learn how to write if I don’t start”. And that was the first issue, which – the whole story just fire-hoses across the page like crazy, with a lot of threads that I meant to come back to but never managed to. I spent the whole second year of publishing in sheer terror of how I was going to make the story narrow to a point, but people do assure that me that despite the fact that it’s my first creative writing effort of any kind, that it does actually make sense (laughs) – in the end!

Jenni: So you hadn’t done any mini-comics as a preparation, or anything like that?

Carla: I did do the first three issues as – well, they were enormous, so I don’t know if it’s proper to call them mini-comics. I didn’t know anybody who was doing mini-comics, I just knew vaguely that you could photocopy a book, put a staple through it, call it a comic… but I didn’t realise you could make mini-comics small… [Audience laughter]

So, there’s goofy old Dave Sim on his soapbox, ranting and raving about how you have to get THESE materials, and work on THIS paper and do THIS, and – I suppose that was a good enough place to start, I say just do it, just grab some materials – here’s what a lot of people use – if you find you like something else, use that, but just do it.

I did a fourteen-day ‘boot camp’, which is still very useful for anybody, at whatever level of professionalism. Basically, the idea is that you do a page a day for fourteen days, finished – no, “I was gonna fix this”, no, “I was gonna go back and do that”, just ready, ready to go, no more worries. And if at the end of fourteen days, you don’t have fourteen pages, you have to examine your method, and decide what kept you from doing it, and make a choice. If you didn’t do it because you had a family emergency, that’s one thing, but if you didn’t do it because you really felt like sitting at home and watching Buffy reruns, well, you made that choice!

And for those of us who have no background as working artists, and haven’t been doing illustrations or commercial work for ten years, this is a way of getting perspective, because we all have to have day jobs, we all have to bow to the vicissitudes of life, and it changes a lot – have you ever seen someone who starts doing minis, and within a few years of doing that, their art style completely changes? That’s just the efficiency of working regularly coming into play.

Jenni: And perhaps, bringing in all sorts of different views that, maybe when they started, they weren’t thinking in that manner… We’re all different people a few years down the line. One example is Andi Watson, who, when he started doing Samurai Jam was extremely blocky, very rubber-stampy, great stuff in itself, but light-years away from what he’s doing nowadays. That sort of change is very natural, but you were taking from it the lesson, not to say, “Oh my God, this isn’t finished, I can’t put it out because I haven’t been able to do this, I can’t draw that…” It’s all going to change, it’s all going to be fluid, it’s going to change perhaps in ways you never thought of a few years down the line.

Carla: It’s a question of learning to love progress, rather than the finished work. Nobody’s ever satisfied with what they do, you’re never going to have enough time or money to do all of the fixing and twiddling you want to do, so it’s a question of being satisfied to a certain degree, and then just keep moving, because the next one will be better!

Jenni: I should say at this point – I should have said when we started – that I do like these things to be quite informal, so if you’ve got questions and stuff, do speak up, fold them into the conversation. Damien, you’re quick off the mark!

Q: You were talking about the need for a day job – do you have one yourself?

Carla: I did, back when I started Finder. I haven’t now, for the last three and a half years.

Q: So is Finder now self-financing?

Carla: It is, yes. It’s taking care of itself now.

Jenni: But you’ve really worked hard at making it a business proposition, and concentrating on all the details that make it a solid, ongoing concern…

Carla: Oh, definitely. I’m financially safe. I’m not going anywhere anytime soon – unless something really untoward happens – but yeah, for the first three and a half, four years I had a day job, I worked at one of those gigantic Borders bookstores. The biggest one in the chain, actually, lucky me! And it was funny because the thing that kept me there for the longest time was not working the floor as a clerk but when I moved into the back and started unboxing.

We went through something like three tons of books a day at that monster-huge store, and, really, everybody… all good nerds love to browse a bookstore, and you don’t browse a Borders much because you know what’s going to be there. But in the back, anything could come out of a box – a big book on rare orchids, a little book on knitting with dog hair – [Audience laughter] – Real book! Real book! It had a picture of a woman on the front with a fuzzy sweater and a Scottie… That kept me there for the longest time.

Q: What were your early experiences of comics? How was it coming in as an outsider?

Q: What were your early experiences of comics? How was it coming in as an outsider?

Carla: The first convention I ever went to at all was San Diego in that first year, 1996. I had a stack of about 150 ashcans, and I shuffled up and down the tables like a typewriter ball, and everybody I found whose name I knew, whose work I loved, got a copy, as if it were my calling card, and I said something like “I like your work, I hope you’ll like mine”, and then I ran away!

Jenni: What sort of response did you get from that?

Carla: Out of the 150 copies, I got about half a dozen of the coolest letters I’ve ever had. I got a three-word response from Donna Barr, I got an entire critique from Charles Vess – I don’t know till how he managed to fit it all on the postcard! I got six really cool letters, the sixth of which was this really long, left-handed compliment from Dave Sim, which I still treasure…

Jenni: How ‘left-handed’?

Carla: Oh, for starters, “Well, you’re going to have a leg up in this business – because you’re a woman!” And “You’re going to be handicapped in this business – because you’re a woman!” “But nonetheless, it’s very good – if you keep up with it…”

Jenni: “If you don’t go off and disappear, and have a child or something…”

Carla: That kind of treatment was not necessarily the worst thing I could have been given. That’s the kind of candy/whip approach that keeps me working. That’s what my roadie’s like – apart from the “woman” part! “If you keep on working on this, it’ll be great – so get back to work!”

But the point of the six letters was not to make me feel good, although it did. The one by Charles Vess I still have pinned up on the wall at home, because he was the first professional to offer me a piece of criticism that I still use today, which was to use silent images to set the tone and mood of a scene. Which is, of course, what Charles has always excelled at. But the main thing about those six letters is that I could pull little quotes out of them! They were spontaneous… You know that there’s a chance, if you’re anyone in this industry, tall or small, there’s a chance whenever you write a fan-letter that someone will want to use your name. But honestly, it’s better that way, because when you ask someone for a quote, they go into ‘book-report’ mode! “Oh no, I’m nine again, and I have to write something clever…” You never, never get quotes out of people like that, it’s like pulling teeth.

Jenni: Or it just gets over-done, like, if I see a book that’s been blurbed enthusiastically by Anne McAffrey, it’s “Okay, that’s not necessarily a sign of any distinction, because she does that to everybody!” I like her books, I read them, but…

Carla: That doesn’t necessarily mean that what she enthuses about is outstanding.

Q: “Tolkien at his best!” [Laughter]

Carla: Oh, Tolkein at his worst was kind of interesting, too (laughs) that would be a cool left-handed compliment!

Q: The extensive footnotes that accompany each story…are we supposed to read them with, or after the stories?

Carla: I would read them after. I make them after – long after, in some cases! Many’s the time people have said there was a wonderful little bit of business in a footnote, and asked why it wasn’t in a story. I have to just say, “Well, I hadn’t thought of it then!” As opposed to academic footnotes, these are kind of ‘fake footnotes’, I don’t even write them until months and months afterwards.

I first started doing them as a way of getting rid of back issues. I’d bundle a group of back issues together, a storyline, and I thought, “If I’m gonna sell these, I need to give people a toy with it.”, so I just wrote down all the notes and stuff that didn’t fit! Next thing I know, instead of the little free fact sheet, which is what I had in mind, I had a twelve-page mini-comic! It actually turned out well, because it was a way for me to get a little perspective, looking back on my own work, seeing the threads that I missed, seeing the structure that I didn’t see beforehand, see some of the things that people reading the books would ask, “Did you mean this? Or this?”

I’ve gotten a lot of my better later story ideas, and a lot of the underpinning, simply from doing the footnotes. So, yeah, I’d read the story first, and then get the footnotes!

Q: Why did you decide to have a male character as your lead?

Q: Why did you decide to have a male character as your lead?

Carla: Erm… because I sensed a lack of beefcake in the market? [laughter]

Well, I… honestly, that character’s been in my head since I was four. Of course, back then he didn’t look anything like that, but there’s always been the consistent internalised voice in the back of my head, and whatever that core is, he’s in there. That core has actually inspired several characters, there’s Jaeger, there’s Lynne, there’s a couple of others that haven’t really come into the story yet, but they’re in it, or rather, it is in them.

The monster in Dream Sequence is also in that core, and in a way the monster is a reflection of that mechanism, because when I come back to those characters in Dream Sequence, you’ll see that most of the characters who survived the events of that story each have one of Magri’s monsters planted in their skulls. Some of them are going to do very well, better with their lives than they ever thought they would. The others are going to self-destruct.

Jenni: The whip and carrot approach either whipping them onwards, or else whipping them over the edge?

Carla: Exactly. And that’s the nature of the thing that’s in my head; it’s the same thing that told me that I was worthless and rotten when I was five, when I was whiny and didn’t want to do as I was told, it’s the same thing that tells me I can go a little further, I can push a little harder, I can make this make sense, now. So, for whatever reason – go ask Freud – that voice, that character, is male.

Q: You’ve mentioned that the rest of your family are also independent and entrepreneurial. Do they have anything approximating the voice you’ve just been talking of?

Carla: I know that some other forces have contributed to it…What can I say? I’m the only book person in the family, so if they have that voice, I doubt seriously that they’ve recognized it or know it for what it is. And who knows whether it’s worth it, for someone who’s not writing a story, to even try to figure that out?

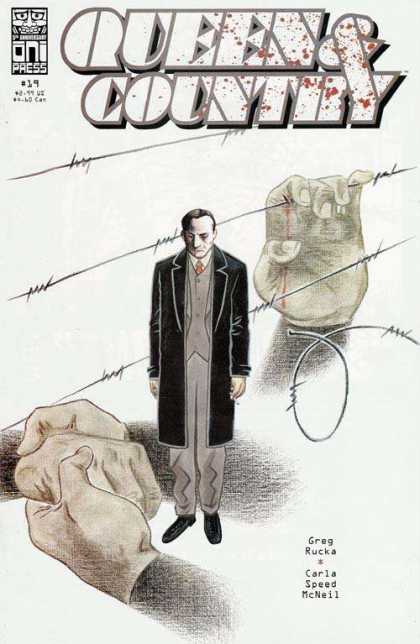

Q: What’s the deal with Queen & Country?

Q: What’s the deal with Queen & Country?

Carla: Oh, now that’s funny. I hadn’t been particularly looking for side work, but Brian Wood asked me to do a pin-up for Pounded, so I drew this female character with a bunch of her big buff buddies at the back, and he said he loved it, and he asked me to do a run on Queen & Country, and I said, “What the hell is Queen & Country?”, so he sent me a bunch of stuff, and…

The back story on this has to do with my husband. My husband is fictionally challenged. He was a Russian Studies History Major, he can tell you anything you’d ever want to know about Eastern Europe, within a certain pair of centuries, but apart from that and computer books and John Dos Passos novels, he just didn’t read books growing up – which is just incomprehensible to me. He doesn’t make references to fictional characters in conversation, he doesn’t talk about movies that he’s liked, although there are some… So, I was reading this bunch of Queen & Country stuff, and Warren Ellis’ introduction was all about the British TV show on which Queen & Country was mostly based, The Sandbaggers. I hadn’t heard of it, but Mike leaned over my shoulder and said, “Oh yeah. Sandbaggers. Best TV show ever made.” [Pulls dumbfounded face][laughter]

So I said, “What?”, and he sat down and explained to me for fifteen minutes, how rare a thing it was to have a realistic depiction of intelligence work. I live in a Government town; practically all of the people I know work at one of these great ponderous Governmental spookshows one way or the other, and you get used to the way they think and what they do, and you sit down and you sit down and watch The Sandbaggers, and yeah, it is like that. I mean, I don’t know many field operatives, but I know the people who push typewriters, and even though this wasn’t a big show, and the BBC probably couldn’t afford fancy sets, the dingy office look was perfectly accurate!

Jenni: Realism by budget stealth…

Carla: So I thought about that for a few minutes, then I started reading the story, which was really interesting, and I ran off and grabbed a set of Sandbaggers DVDs, and that was really interesting! So, I had no reason not to do it, especially since I had a built-in audience who didn’t read – but he’d read this!

Q: Do you work from a full script beforehand, or do you just get it down on the page?

Carla: With my own work, I do outlines, I don’t do full script. I think it would be exhausting to do a full script. The few times that I’ve had to script for a section, even just a scene, to make it very, very clear who’s saying what, and where, and how many panels, blah-blah, in order to get feedback for it from one of my local buddies, it’s just exhausting to explain everything out that way, and then have to draw it!

So what I start out with is a generalised outline; “The story starts here, I want to hit this, and this, and this… ” like the way Neil Gaiman describes it, like going on a train trip. You’re going to start off at A, end up at B, and there’s any number of routes you can get to B, but you know which towns you want to hit in the middle.

If I sit down and try to write the whole script out at once, I will be a little quivering bundle of nerves the whole time, because it’s just – it’s a lot to cram in all at once, I’m used to the story evolving in a slightly more organic way. If I get stuck on something, I know it’s because there’s a piece missing, and I just have to, you know, cool off, get away from it, see if I can find something that fits the hole. I usually don’t have any trouble getting past writers’ block that way, unless I just sit in my studio and bang my head trying to figure what the missing piece is without outside influence!

That’s how it works for me. Other people think – and I can certainly see this point – that if you have a full script to begin with, then that’s where you can begin to embellish. You have time to figure out what would be a more interesting symbol structure to get point of this particular story across. Or you can try an alternate blocking for a given scene. I can see the advantages of both ways. It’s just too exhausting for me to do a full script, because then I don’t want to work on it any more. It works for some people to script a story, then pencil it, then ink it, then letter it, but that doesn’t work for me, because once I’ve pencilled it then I don’t wanna fool with it no more!

I have gone into my sprint speed from time to time and done two pages a day for long stretches, which is what I was doing for the whole Queen & Country thing, doing two books at once, and I’ll do it again, I’ve gotten better at it, my hand doesn’t hate me quite as much, but I tend to not belabour the scripts, I just end up with the pages with great chunks of conversation, and if that flows right, then I know the right will fall into place as I go.

Q: Obviously, you’re a writer-artist, so when you were working on Queen & Country off someone else’s scripts, did you find that a liberating experience, or was it more difficult, trying to convey someone else’s voice through your art?

Carla: Not difficult, really, because Greg makes no big deal of – he said from the very beginning, “I have no visual sense. I’m gonna block this out fast and dirty, go back and tweak dialogue, and if you see a way to do a scene that you think works better than what I’ve got, be my guest!”

That was a real boon to me, because it took the pressure off me as to what he’d think if I fiddled with it, because basically if you did it straight from what Greg writes, you’d have six panels per page of two angry profiles! So he doesn’t care if you break up the page a different way. I love it when he gives me page after page of five-panel descriptions, because that means I can break up those five panels, which inevitably have twelve things going on in them, into a series of panels to focus on these things when some things need to be in the foreground. It’s been fine, it’s been fun, really.

Jenni: An obvious question here, then, is what about the other artists on Queen & Country? Do you look at their pages and find yourself thinking, “Well, now that I know what his scripts are like, I would have done that differently,” or is that not something that you…

Carla: Not on Queen & Country, but, God help me, I’m actually reading Wolverine right now, because Greg’s writing it, and Daerick Robertson is doing some really interesting breakdowns on that book. Because I know what Greg’s scripts are like, so I’m “that would have been one of his basic six-panel grids, but Derek’s gone and done this and made this really intricate…” , and Greg loves his two-page speads. Looves ‘em. And I am no good at them. I hate ‘em, because it’s just in my brain to read this half of a pair of pages and then the other half. But Daerick’s doing these layouts that are like – what’s that artist who does rectangles? [various artists’ name are shouted from the audience. They settle on Mondrian.] Daerick’s doing layouts that, just taken on face value, look like Mondrian. And yet they’re still very effective. I look at them and go, “Okay, if you did that as a movie storyboard, you really would need to have those characters in the foreground, you couldn’t take that tiny little panel and make it work,” but still they work as comics, which is something that’s really made me stop and think as to whether I really need such tight focus on this panel or that panel, or whether I could just let the panel shape recede and make an interesting pattern.

Q

: Going back to what you were saying about your day job in Borders – it’s often been said that the only way to progress as an artist is to lock yourself away…

Carla: How can you? You’d starve! That’s the Grand Wish. “If I only had enough time, I could do whatever I wanted.” Well, you’re never going to have enough time!

It all comes down to, what do you have to do to be satisfied with your work? How have you managed to streamline your work into something that you can use? I have had, perhaps too much time on my hands, because I spend so much time diddling around with that meticulous crosshatching, which is a pain, let me tell you, because if I didn’t do it, if I were Jaime Hernandez and I knew exactly where to spot blacks on a page so that the page balances, I could do five pages a day! Bliss! I could just do a sequence, and if I didn’t like it, I could just – toss it away – because there’d be plenty of time to do another one!

Q: I don’t think that’s what he does. [laughter]

Carla: No, but I could do it! It’s like doing a day’s film shooting, and when that scene hits the cutting room floor, “great, that’s another one for the DVD”. I could do the Extended Director’s Cut later for the trade paperback! If I could just dig myself out of that crosshatching hole, I’d be able to work very, very fast. I pencil a page in about an hour and a half – not counting crowd scenes or really meticulous architecture – doing the brushwork takes maybe an hour; doing the crosshatching… can take anywhere from two hours to the rest of the day! So doing one page a day is okay, but doing two pages a day is brutal…

Jenni: “Crosshatching; Just Say NO.”

Carla: Look at somebody like Andi Watson; his stuff is so clean, it’s so beautiful, but the ‘Ya gotta sit down and do a page’ monkey in me says, “That looks really FAST! Zip, swish, put a few tones in, scan it, you’re DONE!”

You need to find something that means you can do a reasonable amount of work in a reasonable amount of time. If you’re working full-time, then you have to develop a really pared-down style that’s still versatile enough to get your point across. And it does not matter in the least how you go about doing it. If you’re not a Luddite, like me, and you can figure out how to get the computer to do some of the work for you while still being a tool and not a crutch, then that’s what you need to do.

My friend Rachel Hartman, who does an unbearably cute book called Amy Unbounded, she does her book same size as printed. And she just pops ‘em out. She can do that DVD thing, she doesn’t like a scene, she just chucks it on the table; it’s good enough for Artie Spiegelman, it should be good enough for anybody. But it’s different when your work is not reduced to any degree in the process of reproduction. There’s many different roads; you’ve got to do what makes the work happen.

Jenni: And with that it looks like our time’s up, so we’ve got to do what makes Caption happen – head for the bar! Our thanks to Carla for talking to us today. [Applause]

[Following this interview, in October 2005, Carla Speed McNeil announced that she was replacing the paper issues of Finder with an online-only serialisation. Although the series had at that point been collected in seven trade paperbacks, which sold briskly, the sales of the periodical comic had stagnated. Lightspeed Press issued the eighth paperback, Five Crazy Women, comprised mostly of web-only material, but no further paperbacks were announced. In late 2010, Dark Horse Comics solicited the first volume of The Finder Library, a hardcover archive which will collect the out-of-print paperbacks Sin-Eater 1 & 2, King of the Cats, and Talisman. The online Finder continues with the story Torch]

Transcription and framing text by Will Morgan.

Tags: Carla Speed McNeil, Finder, Queen and Country

Interesting.