How I wanted to write Batgirl

by Tony Keen 16-Oct-13

Tony Keen ruminates on how he wanted to portray the Dominoed Daredoll, comparing and contrasting her with other ladies of the DC Universe …

Back in my youth (in my case, my early twenties), like many comics fans, I had a fancy to write superhero comics for a living. Fortunately, I never got to do so – most of my plot ideas were rehashed from my favourite stories by other people. But let me tell you who was top of the list of characters I wanted to write. Not the obvious ones, like Superman or Batman. I did want to write the Avengers, and Captain America. But top of the list of characters I wanted to write was Batgirl.

Back in my youth (in my case, my early twenties), like many comics fans, I had a fancy to write superhero comics for a living. Fortunately, I never got to do so – most of my plot ideas were rehashed from my favourite stories by other people. But let me tell you who was top of the list of characters I wanted to write. Not the obvious ones, like Superman or Batman. I did want to write the Avengers, and Captain America. But top of the list of characters I wanted to write was Batgirl.

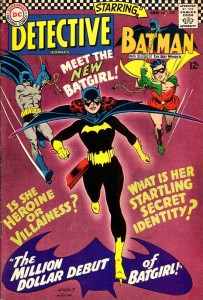

Technically the second Batgirl (though the first was a hyphenated Bat-Girl), this heroine was created as a character that could be employed in the Batman television series in the 1960s, and simultaneously appeared in the comics (in a different, and rather less gaudy, costume, designed by the late Carmine Infantino). She was Barbara Gordon, daughter of Batman’s ally Commissioner Gordon.

Technically the second Batgirl (though the first was a hyphenated Bat-Girl), this heroine was created as a character that could be employed in the Batman television series in the 1960s, and simultaneously appeared in the comics (in a different, and rather less gaudy, costume, designed by the late Carmine Infantino). She was Barbara Gordon, daughter of Batman’s ally Commissioner Gordon.

Why did I want to write her? Because she was cool. She was more than just a female knock-off of Batman. Sure, she was a female knock-off of Batman, but she was never as broody or miserable as Batman. When written properly, she was of a lighter disposition than Bats, but she still took her superheroics seriously, and wasn’t frivolous. After all, this was an independent career woman, with a Ph.D., who had been head of a major public body – the Gotham Public Library – and subsequently a United States Congresswoman.

Of course, sometimes she was badly written, especially in the early days, when writers could get away with more sexist nonsense than they can now. So sometimes she employed Bat-compacts, carried a Bat-purse, or stayed out of a fight because she had a run in her tights (though that turned out to be a ruse to distract the bad guys so that Batman and Robin could clobber them).

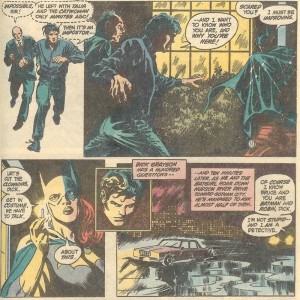

But sometimes she was written brilliantly. My favourite Batgirl moment is one of the first I read, in Detective Comics 526, the five hundredth appearance of Batman in Detective, back in 1983. The writer was Gerry Conway, who generally is a workaday comics writer, but capable of occasional moments of brilliance (aged twenty, he wrote the classic death of Gwen Stacy story in Amazing Spider-Man). Here, the overall story is Conway being pretty mundane. But that Batgirl moment…

Dick Grayson and Alfred are at Wayne Manor, when they see the famous silhouette of Batman at the window. But they know (for reasons I don’t recall, and which don’t matter) that Batman can’t be there, so who is this? It turns out to be Batgirl.

“Scared you?” she says. “I must be improving.”

She goes on to explain that, of course she knows Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson are Batman and Robin, she isn’t stupid after all, but she let them believe she didn’t know their secret identities because it seemed so very important to their male egos that she not know.

One of the other things I always liked about Batgirl was her costume. Okay, she was at first saddled with impractical high-heeled boots, but apart from those, it deviated from the standard superheroine costumes. Most superheroine costumes look like swimsuits or lingerie, or both, and have lots of bare flesh exposed. This applies even to a character who supposedly represents strong womanhood, like Wonder Woman. Many costumes, such as the Black Canary’s original outfit, seem more appropriate for the boudoir (admittedly, a kinky boudoir) than for the mean streets. Batgirl’s Earth-Two equivalent, The Huntress, was originally saddled with a one-piece tank suit, split down to the bottom of her breasts (or in some depictions halfway from there to her navel), and thigh length boots. And that was itself not as bad as the costumes Dave Cockrum and Mike Grell inflicted on the female members of the Legion of Super-Heroes, which were often barely there at all … but still.

One of the other things I always liked about Batgirl was her costume. Okay, she was at first saddled with impractical high-heeled boots, but apart from those, it deviated from the standard superheroine costumes. Most superheroine costumes look like swimsuits or lingerie, or both, and have lots of bare flesh exposed. This applies even to a character who supposedly represents strong womanhood, like Wonder Woman. Many costumes, such as the Black Canary’s original outfit, seem more appropriate for the boudoir (admittedly, a kinky boudoir) than for the mean streets. Batgirl’s Earth-Two equivalent, The Huntress, was originally saddled with a one-piece tank suit, split down to the bottom of her breasts (or in some depictions halfway from there to her navel), and thigh length boots. And that was itself not as bad as the costumes Dave Cockrum and Mike Grell inflicted on the female members of the Legion of Super-Heroes, which were often barely there at all … but still.

Even when superheroines don’t expose flesh, their outfits are usually light coloured, such as the yellow of Batgirl’s predecessor, Batwoman. Combine that with the usual skintight superheroine costume, and you end up with costumes such as that of Black Orchid, which draw attention to the body. Okay, many male superheroes have costumes that similarly draw attention to the body (after all, the Sub-Mariner has spent almost his entire career wearing nothing but a particularly tight pair of Speedos, which explains a lot). But there were plenty who don’t, and besides, the men are generally portrayed in other ways as more than simply sex objects (see much online discussion).

Batgirl’s costume was different. Yes, it was skintight, but it was coloured in dark hues, predominantly blue-black. She wore a cape that could envelop her. The only exposed flesh was, unusually, her lower face. Few superheroines wear a full cowl, most going with a domino mask (e.g. the Huntress) or no mask at all (e.g. Wonder Woman); Jim Lee gave Batgirl the domino mask look in All Star Batman and Robin the Boy Wonder. The only other superheroine of the 1960s that I can think of whose costume gave this little emphasis to her body as Batgirl’s is Sue Storm, the Invisible Girl.

I’d have kept all of this – maybe changed her costume a bit, making the yellow bits white and losing the hair. And I’d’ve got her the hell out of Gotham, so she no longer had Bruce looking over her shoulder.

Then, in 1988, along came The Killing Joke, by Alan Moore and Brian Bolland. I’m not a great fan of The Killing Joke. I think it’s a distinctly minor Moore work, and in terms of definitive portrayals of the Joker, this one falls short of the Steve Englehart/Marshall Rogers 1978 version. I know I’m in a minority here, though at least I’m in good company, as neither Moore nor Bolland like it much either. (Though Chris Garcia, one of the editors of Journey Planet, in which this piece first appeared, notes that The Killing Joke is his single favourite Batman comic ever.)

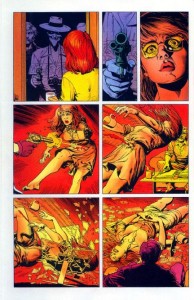

My views of The Killing Joke are no doubt influenced by what happens to Batgirl in the course of this story. Barbara Gordon is shot and paralysed by the Joker. This has attracted a lot of feminist criticism, and rightly so – it is a classic example of a phenomenon that is found all too often in comics and other dramas, doing something nasty to female characters in order to motivate their male associates. At the time it seemed a bit like pulling the wings off flies (somewhere I said so at the time). Moore himself now rather regrets doing this.

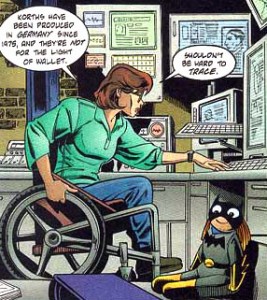

Barbara Gordon as Oracle. Her ability to extract data has been underplayed since she was restored to full walking ability.

Step forward Kim Yale. Yale was incensed by the treatment of Batgirl in The Killing Joke. Together with her husband John Ostrander, she came up with a way of restoring dignity to the character without simply negating The Killing Joke, which would not, at that point, have gained editorial approval. Barbara became Oracle, a woman living with her disability, and acting as a first rate source and processor of information, who later became the key organiser of the “Birds of Prey” team. This was the most positive depiction of disability in comics since Professor X.

Meanwhile, others took up the Batgirl identity, Cassandra Cain and Stephanie Brown. In the interim period, Barbara appeared in other media – as a pre-teen in Batman: The Animated Series, in the movie Batman and Robin, made into Alfred’s niece, and in the tv series Birds of Prey as Oracle. Then, in 2011, as part of DC’s relaunch, she was cured of her disability, and took back the Batgirl identity. I’m not at all sure about this. I never wanted Barbara to be crippled in the first place, but restoring her seems disrespectful to the work of Yale and Ostrander and those that followed them. So for the time being I ignored the issue, and turned instead to 500 pages of early Batgirl stories, Showcase Presents Batgirl.

Eventually I did pick up the first collected volume of the New 52 Batgirl. There’s a lot to like about it. It’s well-written, by Gail Simone, who originated the idea of “women in refrigerators”, so has credibility when it comes to dealing with issues in Barbara’s past. Simone is clearly a Batgirl fan, and Barbara is presented as a real individual, who does things differently from Bruce Wayne. The corporate decision to restore Barbara’s legs is handled sensitively in terms of the story. But there’s something that still unsettles me about this, and I think in the end it’s something that is a problem with comics ever since Jean Grey was brought back – these days nothing in mainstream comics has any lasting consequences for the characters. Sooner or later, all the really bad stuff in a character’s life (and sometimes, the really good stuff, like the marriages of Clark and Lois and Peter and Mary-Jane) gets undone, and the characters go back to square one. This isn’t Simone’s fault, of course. It’s corporate comics, and it’s why I read so few these days.

Eventually I did pick up the first collected volume of the New 52 Batgirl. There’s a lot to like about it. It’s well-written, by Gail Simone, who originated the idea of “women in refrigerators”, so has credibility when it comes to dealing with issues in Barbara’s past. Simone is clearly a Batgirl fan, and Barbara is presented as a real individual, who does things differently from Bruce Wayne. The corporate decision to restore Barbara’s legs is handled sensitively in terms of the story. But there’s something that still unsettles me about this, and I think in the end it’s something that is a problem with comics ever since Jean Grey was brought back – these days nothing in mainstream comics has any lasting consequences for the characters. Sooner or later, all the really bad stuff in a character’s life (and sometimes, the really good stuff, like the marriages of Clark and Lois and Peter and Mary-Jane) gets undone, and the characters go back to square one. This isn’t Simone’s fault, of course. It’s corporate comics, and it’s why I read so few these days.

An earlier version of this article was first published in Journey Planet 13, as part of a section on “Women and Comics”. My thanks to editors James Bacon and Chris Garcia for permission to reproduce it here.

Tags: Barbara Gordon, Batgirl, Batman, DC, The New 52