Flying the flag: the super-patriots of the early 1940s

by Tony Keen 28-Apr-14

Tony Keen meanders his way through those who preceded and followed Captain America.

[This is a revision of an article I wrote in 2008 for a tribute ’zine to the late Steve Whitaker. Among many things, Steve was an extremely knowledgeable comics historian. I never had as many conversations about that with him as I’d have liked. But around 2005, we had an exchange on 1940s comics, and the phenomenon of the ‘super-patriot’. It seemed to me that the most appropriate tribute I could pay to Steve was to present my thoughts on the subject. And now I’d like to share them with you. I hope Steve would have been pleased with this.]

[This is a revision of an article I wrote in 2008 for a tribute ’zine to the late Steve Whitaker. Among many things, Steve was an extremely knowledgeable comics historian. I never had as many conversations about that with him as I’d have liked. But around 2005, we had an exchange on 1940s comics, and the phenomenon of the ‘super-patriot’. It seemed to me that the most appropriate tribute I could pay to Steve was to present my thoughts on the subject. And now I’d like to share them with you. I hope Steve would have been pleased with this.]

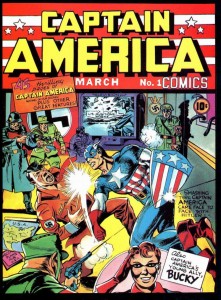

The epitome of the American flag-draped patriotic superhero is, of course, Captain America, created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, whom I’ve discussed in another article on FA Online. It’s easy to assume that he was also the first, not least because that’s the way, at least by implication, Simon and Kirby told the story. Kirby once said that Cap was created because America needed a super-patriot, as if there wasn’t one already. But, as Will Morgan writes in The Slings & Arrows Comics Guide, Captain America was not the first. (It should be noted that in the following, I use the term ‘super-patriot’ as a convenient label—not all of them had superpowers.)

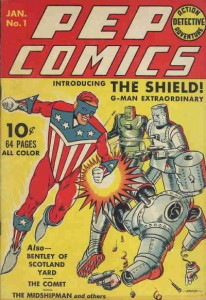

The honour of being the first super-patriot belongs to the Shield, first published in Pep Comics #1, cover date January 1940, a full year before Martin Goodman, owner of Timely Comics (or whatever it was called that week), published Captain America Comics #1 (March 1941). (Of course, the comics actually appeared on the newsstands several weeks or even months before the cover dates. Pep Comics #1 appeared in November or December 1939, and Captain America Comics #1 in December 1940.) Pep Comics was published by MLJ Magazines, who later became Archie Comics, after the most famous character ever to appear in the pages of Pep.

The honour of being the first super-patriot belongs to the Shield, first published in Pep Comics #1, cover date January 1940, a full year before Martin Goodman, owner of Timely Comics (or whatever it was called that week), published Captain America Comics #1 (March 1941). (Of course, the comics actually appeared on the newsstands several weeks or even months before the cover dates. Pep Comics #1 appeared in November or December 1939, and Captain America Comics #1 in December 1940.) Pep Comics was published by MLJ Magazines, who later became Archie Comics, after the most famous character ever to appear in the pages of Pep.

In fact, in one respect the Shield was also not the first. Superman creator Jerry Siegel had a strip that had begun in All-American Comics #1 (April 1939), called Red, White and Blue. These three agents had no formal costumes such as Superman or Batman had, or powers. But they were nonetheless patriots in comic books, whose visual appearance was built around the American flag. One might also cite Timely’s American Ace, created for the never-distributed Motion Picture Funnies Weekly in 1939, and actually seeing print later that year in Marvel Mystery Comics #2 (December 1939). He was, however, a pilot, with no powers, and not even a nod towards a patriotic costume, such as was shown by Red, White and Blue.

The Shield’s claim to be the first super-patriot must therefore stand (even when taking into account the fact that Simon and Kirby sat on Cap from the autumn of 1940 while driving a hard bargain with Goodman). The Shield was created by Irv Novick, later famous for his 1950s collaborations with Robert Kanigher, and who then went on to draw some fine Batman stories in the 1980s. The Shield’s real name was Joe Higgins. His father, Tom Higgins, had been working on a formula for super-strength. Before he could complete the formula, Higgins senior was killed by foreign agents, leaving the son to finish his work. Joe became a superhero, working with the FBI, for whom he was ‘G-Man Extraordinary’.

There are some rather notable similarities with the Shield’s back story in Captain America’s origin. Cap too was the recipient of a super-soldier serum, who became a hero after the scientist who created the formula was killed by a foreign agent; Cap then worked with the US Army. And a stars-and-stripes bedecked shield was a key part of both characters’ iconography. MLJ certainly thought the origin of Captain America was a little too familiar. They threatened Martin Goodman with a lawsuit, which Goodman averted by agreeing to change the shape of Cap’s shield, which was just too close to the emblem the Shield wore on his chest. This is the real reason Captain America changed from his original traditionally-shaped shield to the now-iconic round model.

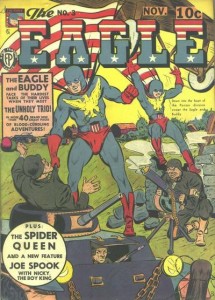

A later appearance of the Eagle and Buddy, cover-dated November 1941, by which time their costumes had been modified to make them appear more patriotic—note especially the red-and-white-striped capes.

In fairness, Simon and Kirby were only doing what everyone did in the 1930s and 1940s—once someone had a good idea, others rushed in with imitations. This happened with Superman, rapidly mimicked by the likes of Masterman and Captain Marvel, both published by Fawcett Comics. And, as we shall see, the same thing was to happen with Cap.

Simon and Kirby put Cap together by combining elements of the Shield with some taken from Fox Feature Syndicate’s Eagle, who had appeared in Science Comics #1 (February 1940); from him Simon and Kirby seem particularly to have taken some costume ideas, from the character’s second costume, which appeared in Science Comics #7 (August 1940). It is possible also that the idea of a kid sidekick for Cap derives from the Eagle. The Eagle’s was Buddy, the Daredevil (no relation) Boy, who obviously is similar in name to Cap’s sidekick Bucky Barnes. However, Buddy did not appear until Weird Comics #9 (December 1940), and it is more likely that both Bucky and Buddy were modelled on Robin, the Boy Wonder, who had appeared in Detective Comics #38 (April 1940); similarly, the Shield acquired a sidekick, Dusty the Boy Detective, in Pep Comics #11 (January 1941).

The Shield was certainly selling well enough to warrant copying, and other imitations had appeared. I’m not convinced by attempts to claim Manowar, who first appeared in Target Comics #1 (Novelty, February 1940), as a super-patriot—despite the commitment to warfare implicit in the name, he doesn’t have the right sort of costume. And whilst Skyman (Big Shot Comics #1, Columbia, May 1940), did have a costume in which the main colours were red, white, and blue, it was not overtly patriotic in its inspiration.

I’ve already mentioned the Eagle and Buddy, though when the Eagle first appeared there was nothing particularly patriotic about his costume, and he was not at first particularly portrayed as an American Eagle. His second costume was primarily red and blue, and he appeared in front of the Stars and Stripes on the cover of Weird Comics #16 (July 1941). But he did not really start draping himself in the flag until his third costume, which debuted in Weird Comics #17 (August 1941); as we shall see, this was almost certainly a reaction to the success of Captain America.

Ed Smalle’s strip War Eagles debuted in MLJ’s Zip Comics #1 (February 1940). It featured two airmen, twin brothers, who became fighter pilots in the ‘British’ Air Force (or Royal Air Force as we know it) in order to carry on a spat with a German sportsman (good to know that their motives were noble). They were certainly patriots. But, as with the American Ace, they weren’t superheroes (or even costumed heroes).

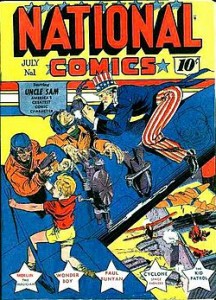

A much stronger case for beating Cap (though not the Shield) to the super-patriot image can be made for Uncle Sam, created by Will Eisner. In an act of chutzpah, Quality Comics had stolen the name of one of their main rivals, National Comics, for one of their own titles. (National had the last laugh, buying out Quality and most of its characters in the 1950s.) To give some justification for the title, National Comics #1 (July 1940) saw the debut of Uncle Sam, accompanied by the non-costumed Buddy Smith. With his top hat and tail coat, Uncle Sam was a most untypical looking superhero, but clearly a patriot, drawing on a personification of the United States government that appeared in newspapers in the nineteenth century. He sold well enough as well, appearing in print until 1944.

Another character sometimes cited in this context, the Destroyer, was first seen in Mystic Comics #6 (Timely, August 1940). He did not have a patriotic costume. He was, however, vehemently anti-Nazi, a quality which, as we shall see, was shared with the super-patriots.

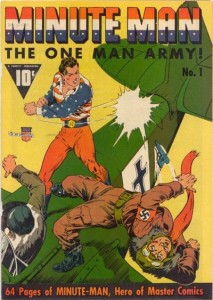

Meanwhile, Fawcett Comics had Minute Man (or Minute-Man), ‘the One Man Army’, in Master Comics #11 (February 1941, on sale in November 1940). At the same time National the company (who would become DC) got in on the act, transforming Tex Thompson, who had been in Action Comics since #1 (June 1938) as a non-costumed adventurer, into Mister America, in Action Comics #33 (February 1941; he later became the Americommando in Action Comics #52, September 1942).

What Simon and Kirby may have lacked in originality, they made up with in sheer talent. One of the main reasons that Captain America was more successful than previous super-patriots (and he was—the first issue of Captain America Comics sold nearly a million copies) was that Simon and Kirby simply did it better than anyone else. They (or possibly just Simon, depending on whose story you believe) also designed one of the most effective of the super-patriot costumes, as a glance at some of the others illustrated in this article I think shows (for the worst, check out Super-American, U.S. Jones, and Stormy Foster).

Right from his very first appearance, as seen here, Fawcett seemed unable to decide if Minute Man’s name should have a hyphen or not.

Some of Cap’s predecessors were shortlived—the Eagle and Buddy, for instance, though earning their own title, stopped appearing after the end of 1941. Some of Cap’s successors would disappear after a single strip.

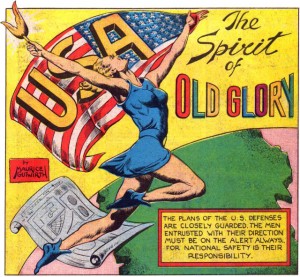

The impact of Captain America was soon felt. A few more super-patriots appeared in the few months that immediately followed the appearance of Captain America Comics #1. One such was Quality’s USA, ‘the Spirit of Old Glory’, the first female example (Feature Comics #42, March 1941); presumably more of a response to Uncle Sam and the Shield than Captain America, since she appeared concurrently with Cap.

The impact of Captain America was soon felt. A few more super-patriots appeared in the few months that immediately followed the appearance of Captain America Comics #1. One such was Quality’s USA, ‘the Spirit of Old Glory’, the first female example (Feature Comics #42, March 1941); presumably more of a response to Uncle Sam and the Shield than Captain America, since she appeared concurrently with Cap.

Brookwood Publications (soon to become Harvey Comics) introduced Captain Freedom (Speed Comics #13, May 1941). Lev Gleason published Captain Battle (the ‘One-Man Army’, as opposed to Fawcett’s Minute Man, the ‘One Man Army’), starting in Silver Streak Comics #10 (May 1941). Again, these characters were presumably in the works before Captain America Comics hit the stands, and the ‘Captain’ part of their names presumably derived from Fawcett’s Captain Marvel (as, no doubt, was the case with Captain America). Similarly ahead of the game were Centaur, with Man of War, a patriotic Captain Marvel clone, appearing in Liberty Scouts #2 (June 1941; the Liberty Scouts themselves were non-super patriots).

Rusty Ryan and the Boyville Brigadiers, as they appeared in Feature Comics #46-52. Pretty blatant, I think you’ll agree.

Quick off the mark in responding to Captain America were Quality; their Rusty Ryan and his Boyville Brigadiers (not ‘Brigaders’!) first appeared in Feature Comics #45 (June 1941), but from Feature Comics #46 (July 1941) started dressing as a Captain America tribute act.

Then, in comics cover-dated August and September 1941, there was an absolute glut of super-patriots, with increasingly contrived names (usually based around some use of ‘America’, ‘Eagle’, ‘Captain’, and/or ‘Flag’) and costumes. The following paragraphs discuss some of them (and I make no claims that I’ve tracked all of them down).

In the August comics, Better Publications (sometimes referred to as Nedor, which was actually a sister publisher, both being part of Standard Comics, and Golden Age publishers are so bloody complicated) brought out the American Crusader, in Thrilling Comics #19. The same month, Helnit (soon to become Holyoke Publications) published Captain Fearless #1. The title character didn’t have the flag-based costume, but his name was clearly influenced by Captain America, and he dressed as an American frontiersman (he was also accompanied by a kid gang, the Young Defenders). The same comic also featured Miss Victory, who survived the swift demise of the title after #2 (which the lead character didn’t), and (long before Robert Lindsay came along) Citizen Smith, ‘Son of the Unknown Soldier’. Smith did not wear a costume, but had the Stars and Stripes in his logo; he was inspired to fight injustice by the ghost of his father, in a very similar way to how Captain Fearless was inspired by the ghost of an ancestor. One suspects the same brief was given to two sets of creators. Citizen Smith didn’t last either.

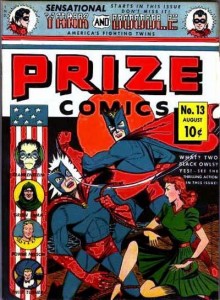

The cover of Prize Comics #13 was designed to associate all the characters inside with patriotic values, not just Yank and Doodle.

Quality came up with their fourth super-patriot (counting Rusty and all his Brigadiers as one), and their second female one, Miss America, in Military Comics #1 (August 1941), the same comic that launched Blackhawk. (This is not the Miss America who was once supposed to be the mother of Quicksilver and the Scarlet Witch; Timely’s character of this name did not appear until Marvel Mystery Comics #49, November 1943). The third female super-patriot to appear under an August 1941 cover date, alongside Miss America and Miss Victory, was Lev Gleason’s Pat Patriot, who made her debut in Daredevil Comics #2; she was (as far as I know) the only singing super-patriot. Like many female super-patriots, Pat tended to fight her battles on the home front—attacking the enemy overseas was left to the boys.

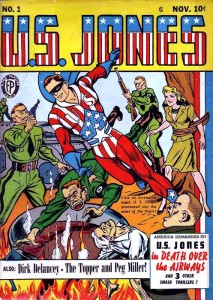

U.S. Jones soon gained his own title, but lost it after two issues. He has the second worst super-patriot costume. If Liberace designed a super-patriot costume…

August cover dates also saw ‘fighting twins’ Yank and Doodle, in Prize Comics #13 (flagship title of, well, Prize Comics), the Sentinel (Liberty Scouts #3, Centaur), U.S. Jones (Wonderworld Comics #28, Fox), and Yankee Eagle (Military Comics #1, Quality). Ace introduced Captain Courageous (Banner Comics #3; Ace tried to make Banner look a more serious proposition by making the first issue #3). The Conqueror, in a patriotic costume, appeared in the appropriately named Victory Comics #1 (Hillman). Our Flag Comics introduced the Unknown Soldier and Captain Victory in #1 (August 1941) and the Flag in #2 (October 1941). Harry A. Chesler, under the ‘Dynamic’ label, topped Captain Victory with Major Victory (Dynamic Comics #1, August 1941). The same cover-date month, as already mentioned, the Eagle changed his costume to one more in keeping with the other super-patriots.

In the September cover-dated comics, the rush eased off a little, but the month still saw three super-patriots. The less-than-subtly named Captain Flag appeared in Blue Ribbon Comics #16 (MLJ Comics); his sidekick was an actual eagle called Yank the Eagle (I am not making this up!). The Fighting Yank (Startling Comics #10, Better Publications) had the same ‘inspired by an ancestor’ origin employed by Captain Fearless and Citizen Smith. Presumably in the small world of comics creation, writer Richard E. Hughes had heard about these series and decided to copy them—or they had heard about his. Finally, Yankee Doodle Jones and his sidekick Dandy turned up in Yankee Comics #1 (Harry A. Chesler/Dynamic); Yankee Comics #2 (November 1941), added Yankee Boy, and in the interests of some form of balance, 1940s Confederate superhero Johnny Rebel.

Shame on you, Super-American! Cap’s punching out the real Hitler, and you’re still tackling ‘the Secret Dictator’. (Also, third worst super-patriot costume.)

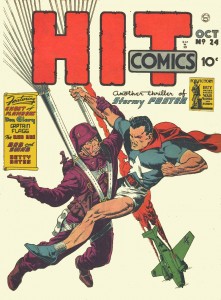

National, who up to this point only had Mister America in the mix, prepared to get a little more in on the act, with the Star-Spangled Kid first appearing in civilian guise in September (Star-Spangled Comics #1; the title may have been a giveaway); he took up his costumed identity the next month, along with his grown-up sidekick, Stripesy. As 1941 wore on, Fiction House introduced Super-American and Captain Fight in Fight Comics #16 (December 1941), at the same time as the appearances of Flag-Man and Rusty (originality in boy sidekick names being in short supply) in Captain Aero Comics #1 (Holyoke), Stormy Foster aka the Great Defender in Hit Comics #18 (Quality; the name wasn’t super-patriotic, but the costume was), and the Liberator in Exciting Comics #15 (Better Publications).

Stormy Foster, owner of the worst super-patriot costume. It’s the shorts, really. Why did anyone ever think those were a good idea?

Arguments can be made for other characters embodying some of the elements of the patriotic hero, such as Lady Fairplay (Bang-Up #1, Progressive Publishers, December 1941). But these arguments can be a little tenuous. My notes also suggest a Miss Liberty of the August 1941 period, but I suspect there is some confusion at work there, as I can now find no actual trace of a character with that name before DC’s Revolutionary War-period character, who first appeared in Tomahawk #81 (July-August 1962). Though, given the sheer number of characters created, and the way in which their names were formed, it wouldn’t surprise me if there was a Miss Liberty in the 1940s.

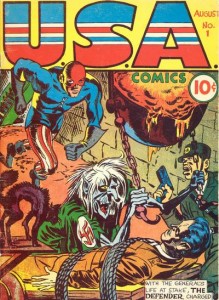

All these super-patriots (all of whom were in print before the United States was officially at war, which, as will become apparent, is significant) were obviously reactions to the success of Captain America, as the sales figures on Captain America Comics became apparent. Sure he was onto a good thing, Martin Goodman also commissioned several imitations for Timely. The Patriot was Ray Gill and Bill Everett’s version of Cap, who appeared in Marvel Mystery Comics #21 (July 1941), and acquired a female sidekick, Miss Patriot, in Marvel Mystery Comics #50 (December 1943). The Defender (not the Great Defender) and (a different) Rusty the Boy Patriot appeared in in USA Comics #1 (August 1941); this was Simon and Kirby ripping themselves off. Mr Liberty also first appeared in USA Comics #1, and became Major Liberty in #2, November 1941). Additionally, the Sentinels of Liberty (Bucky Barnes and his mates) made their first appearance in Captain America Comics #4 (June 1941), in a text story. In the space of a couple of months they were renamed the Young Allies.

Goodman would go on publishing characters along these lines throughout the Second World War, such as Citizen V (Daring Mystery Comics #8, January 1942), the Victory Boys (Comedy Comics #10, June 1942), the American Avenger (USA Comics #5, Summer 1942), the second Fighting Yank (Captain America Comics #17, August 1942), the second Miss America (mentioned above), and the Spirit of ’76 (Captain America Comics #49, August 1945). If nothing else, this would give Steve Englehart a wide range of super-patriots to choose from when he chose to explain who had carried the mantle of Captain America in the 1950s, when the real cap was frozen in the Arctic.

There’s a political element to the super-patriots which isn’t always commented upon. These days, wrapping oneself in the American flag is an image associated with the American Right, and it is easy to link Captain America with those sorts of attitudes, as Mark Millar did in The Ultimates (I discuss this in my article on Cap on FA Online). But in the 1940s, not just Cap, but all the flag-wearing heroes were on the other side of the political fence.

In the so-called Great Debate of 1940-1941 over American intervention in the war in Europe, Captain America and his ilk were all firmly on the side of intervention (it is not coincidental that most of the creators were Jewish). As early as All-American Comics #5 (August 1939), Red, White and Blue were tackling suspiciously fascist-looking enemies. The heroes of War Eagles joined the Royal Air Force before the Battle of Britain had begun; though some US airmen did this (and many more followed as 1940 went on), in theory they were risking their citizenship in doing so.

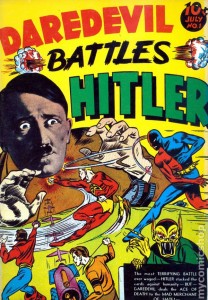

Though Uncle Sam’s costume drew upon how the character was depicted in nineteenth-century cartoons, it would (presumably entirely deliberately) have immediately made people think of James Montgomery Flagg’s 1917 recruiting poster, thus placing the character firmly in the interventionist camp. Tex Thompson became Mister America because Nazis sank an American liner. Red, White and Blue went on to tackle Germans (though Siegel was told to tone down the political content). The cover of Pep Comics #1 shows the Shield fighting robots, but by #2 he was tearing into U-Boats. All this eventually led to classic covers in which superheroes fought Hitler in a war in which the United States was still officially neutral, such as that of Captain America Comics #1, and Lev Gleason’s Daredevil Battles Hitler (July 1941).

Though Uncle Sam’s costume drew upon how the character was depicted in nineteenth-century cartoons, it would (presumably entirely deliberately) have immediately made people think of James Montgomery Flagg’s 1917 recruiting poster, thus placing the character firmly in the interventionist camp. Tex Thompson became Mister America because Nazis sank an American liner. Red, White and Blue went on to tackle Germans (though Siegel was told to tone down the political content). The cover of Pep Comics #1 shows the Shield fighting robots, but by #2 he was tearing into U-Boats. All this eventually led to classic covers in which superheroes fought Hitler in a war in which the United States was still officially neutral, such as that of Captain America Comics #1, and Lev Gleason’s Daredevil Battles Hitler (July 1941).

It’s oversimplifying matters to suggest that the American Left were for intervention and the Right against it. As well as the right-wing industrialists happy to trade with the Nazis that one would expect, there were plenty of left-leaning people in the isolationist America First Committee, for a variety of reasons; there were liberals concerned to avoid the slaughter of the First World War, and Communists automatically supporting Stalin’s every act, which at this point included the non-aggression pact with Germany. But at the core of isolationism were anti-New Deal Republicans, whilst interventionism was widely supported by the sort of liberals who had joined the International Brigades, and who were now risking their citizenship by crossing into Canada and joining the RAF. So, Captain America and the others began as symbols of left-leaning, socially responsible policies.*

It’s oversimplifying matters to suggest that the American Left were for intervention and the Right against it. As well as the right-wing industrialists happy to trade with the Nazis that one would expect, there were plenty of left-leaning people in the isolationist America First Committee, for a variety of reasons; there were liberals concerned to avoid the slaughter of the First World War, and Communists automatically supporting Stalin’s every act, which at this point included the non-aggression pact with Germany. But at the core of isolationism were anti-New Deal Republicans, whilst interventionism was widely supported by the sort of liberals who had joined the International Brigades, and who were now risking their citizenship by crossing into Canada and joining the RAF. So, Captain America and the others began as symbols of left-leaning, socially responsible policies.*

This relates to another reason why Captain America was so much more successful than earlier attempts. In December 1939, most Americans saw no reason to get involved in the European war—France and Britain, people thought, would contain Hitler’s ambitions. This was reflected in comics of 1940 through a certain reluctance to be too overt.

On the one hand, the comics industry was almost entirely staffed by Jews, and young Jews from working-class backgrounds at that. Everyone had known since Kristallnacht in 1938 what the Nazis would do to the Jews (in broad terms, if not the specifics of the Final Solution). These writers and artists thought America should stop it. So they tried to promote this through their stories. On the other hand, potential controversy, and hence lost sales, led to executives wary of any artistic work tackling the issue. Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator was first shown in September 1940, and disguised Hitler under a pseudonym (a humorous one, Adenoid Hynkel). This film was controversial while in production, with speculation that it would not be released; production company United Artists (which Chaplin had formed twenty years earlier) sent Chaplin messages that alarmed him, presumably suggesting they were about to pull out. Indeed, the German consul complained about the movie.

Some senior figures in the comics industry had an eye on possible lost sales if their publications became controversial, and took appropriate action. So, it was often the case that the enemies fought by super-patriots were unnamed, if wearing suspiciously Germanic uniforms and speaking with mid-European accents. The names of Germany and Hitler would be ‘concealed’ through transparent pseudonyms such as ‘Rudolph Hendler’, dictator of ‘Prussland’ (in Jack Kirby’s Mercury in the 20th Century, Red Raven Comics 1, August 1940) or ‘Hiller’ (in a Marvel Boy story in Daring Mystery Comics 6, September 1940, published in June). This latter instance was a last-minute intervention by Martin Goodman, changing what had originally been ‘Hitler’. And this was coming from Goodman, who presided at Timely over one of the more anti-Nazi series of comics. The pseudonyms were, of course, transparent, but that wasn’t the point.

Interesting is the position of Superman. Joint owner of All-American comics, Jack Liebowitz, was also a major shareholder in Superman’s publisher National. Liebowitz ensured that Superman stayed out of commenting on the European war, to the extent that arms dealers seeking to profit from involving America were portrayed as villains. This was partly out of concerns for lost sales, but partly because Superman was so powerful that he could not get involved with fighting Nazis without breaking any connection with reality. Superman’s creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster did produce a strip for Look magazine entitled ‘How Superman Would End the War’, published in the 7th February 1940 issue. Superman simply flies to Berlin and Moscow, kidnaps Hitler and Stalin, and takes them to the League of Nations. The War is then over. This is a perfect illustration of why keeping Superman out of the war was a good idea.

Superman aside, National did tend towards interventionism, though as noted above, they were slow getting on the super-patriot bandwagon. They did have their regular superheroes fight suspiciously Germanic, Italianate or Oriental enemies, as did other companies.

By the end of 1940, the fall of France had shattered the illusion that Europe could contain Hitler. Yet the survival of Britain also further strengthened the interventionist cause; as long as the UK stood against Germany, there was an opportunity for America to intervene, whilst the fall of the island would make American involvement very difficult. So, Captain America appeared at a time when the mood in America was more receptive to the message that the strip carried, and that mood strengthened thorough 1941 (and hence the need to disguise the enemies fought by super-patriots reduced, though it did not go away entirely until war was actually declared). Nevertheless, Simon and Kirby received hate mail and death threats after the publication of Captain America Comics #1, and were menaced outside their offices. The echoes of this controversy continue to reverberate today; recent retellings of Cap’s origin, such as that in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, place Steve Rogers’ volunteering for the Supersoldier programme after Pearl Harbor, not before.

In 1940, however, as we have seen, Cap opened the way for a flood of anti-Nazi heroes, both super-patriots and others, such as Gleason’s Daredevil, who decided that the time had come to act. But let’s not fool ourselves. These comics were not produced because of a massive outbreak of social conscience in US comic-book companies—they came out because the basic concept sold.

In the aftermath of America’s entry into the war, patriotism in comics became more popular, and not just for the existing super-patriots—in 1942 Superman began fighting not just for truth and justice, but also for the American way. More super-patriots inevitably followed. Harvey’s Pat Parker, War Nurse, was a bit of an oddity. ‘War Nurse’ seems a strange superheroic identity, and she certainly didn’t wrap herself in the US flag—but this was partly because she was British rather than American (though American-created, of course), and she was ‘John Bull’s valiant War Nurse’, so intended as a British counterpart to the US super-patriots. In Speed Comics #23 (October 1942), Pat became leader of the Girl Commandos. She first appeared in Speed Comics #13, cover-dated January 1942, so presumably had been planned before America entered the war.

Another character who appeared right on the cusp of conflict was V-Man (V Comics #1, Fox, January 1942), accompanied by his V-Boys. (V Comics is sometimes called V…- Comics, but this is because the Morse code for ‘V’, dot-dot-dot-dash, was incorporated into the comic’s logo.)

With war firmly declared, Fawcett introduced Commando Yank and Phantom Eagle in the same comic, Wow Comics #6 (July 1942). Lev Gleason had the short-lived War Eagle (Crime Does Not Pay Comics #22, July 1942), whose superheroics were supposed to date back to 1929. (Quality’s Captain Flagg, who first appeared in Hit Comics #22, June 1942, was another non-superhero aviator, and is not to be confused with MLJ’s Captain Flag.)

Another Eagle character, American Eagle, together with his sidekick the Eaglet, debuted in Exciting Comics #22 (Better Publications, October 1942)—he was a pretty blatant rip-off of Fox’s Eagle (with a lot of elements of Captain America). National introduced Liberty Belle in Boy Commandos #1 (Winter 1942-1943), one of the few super-patriots who has had any post-war impact, largely through Roy Thomas taking her into his retro-comic All-Star Squadron in 1981. To these we can add Captain Commando (Pep Comics #30, MLJ, August 1942), Crimebuster (Boy Comics #3, Lev Gleason, August 1942), Captain Red Blazer and Sparky (All-New Comics #5, Harvey, September 1943); Red Blazer had appeared as a non-patriotic hero in Pocket Comics #1, August 1941,

There were even two Yankee Girls. The first appeared in Captain Flight Comics #8 (Four-Star Publications, May 1945), but though she had a superhero name, she had no costume or powers. She had first appeared as Kitty Kelly in Punch Comics #1 (Harry A. Chesler, December 1941), and reverted to that name in Red Seal Comics #17 (July 1946), though at the same time she adopted a superhero costume. Captain Flight himself was yet another aviator rather than a superhero. The second Yankee Girl appeared in Dynamic Comics #23 in 1947 (November), by which time the bottom was dropping out of the super-patriot market, though AC comics have made much use of here in Femforce.

A couple of late entries to the genre are to be found in Star Studded Comics (Cambridge House Publishers, 1945, published in 1944), which introduced, in two separate features, Captain Combat and the Commandette. Neither was particularly draped in patriotic costumes. Commandette was an actress and stuntwoman, and her name was simply intended as a play on a female Commando, though in her one appearance, she did fight Nazi saboteurs—but then in 1944, who didn’t? So these two must be considered peripheral elements of the super-patriot picture. (Again, I don’t promise that I have covered all of the post-1941 super-patriots—I have researched these less thoroughly than those of 1940-1941.)

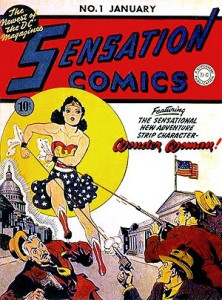

Wonder Woman’s first appearance – note the Capitol and Supreme Court buildings from Washington DC in the background.

One last super-patriot needs consideration. Though they had published Red, White and Blue, M.C. Gaines’ All-American Comics were slow in getting on the super-patriot bandwagon. Indeed, All-American was for the most part pro-isolationist in its stance through 1040 and 1941. When All-American’s super-patriot finally appeared, in All-Star Comics #8 (December 1941-January 1942), it was the most untypical of them all—Wonder Woman.

Why is Wonder Woman draped in the US flag? Though she does travel to America and fight Nazis and other foreign enemies, there is a great deal more to her background beyond simply standing up for American values (though in drawing her inspiration from the Greco-Roman gods, she does parallel an earlier super-patriot, Man of War, as well as Captain Marvel). Could it possibly be that this element was added on to a character already in development, because a super-patriot was needed quickly? Steve Whitaker once supplied me with a scan of an early sketch by Harry Peter, with notes from both Peter and William Moulton Marston (the image later leaked out onto the Internet, though not from me or Steve). Marston’s notes suggest that Gaines made some stipulations about the costume, which might support the theory that the patriotic motif wasn’t Marston’s or Peter’s idea (though the sketch does show her in full Stars-and-Stripes skirt).

Regardless, it remains the case that flag-wearing patriotism has always been a minor factor in Wonder Woman, rather than her whole raison d’être, as it is for Captain America. Perhaps that helped Wonder Woman to be the only one of these heroes to remain in publication through the 1950s, when all the others were cancelled. Of course, in the end, Captain America couldn’t be kept down, and has been a fixed part of the Marvel firmament since 1964. That’s another article, though.

[The research for this article owes much to Michael Eury’s article on ‘Superpatriots’ on SuperHeroMultiverse.com (archived on the Wayback Machine).]

* A very interesting essay by Joseph Oldham on Captain America: The Winter Soldier states, ‘in evading the obvious role of a straightforward assertion of American individualist supremacy that his creators (in both real life and the diegetic narrative of The First Avenger) intended, he has instead come to symbolise something of a conscience for America.’ But it seems clear to me that Simon and Kirby created Cap as a conscience for America, and that this remains hardwired into the character’s DNA.

Tags: 1940s comics, Captain America, Jack Kirby, Joe Simon, super-patriots, Superheroes, superpatriots, The Shield, Wonder Woman