Krazy Kat: Modernism and Influence

by Martin Skidmore 01-Jan-11

There is arguably no comic work as canonical as Krazy Kat. But unlike other revered classic newspaper strips, it was never terribly popular; indeed, a lot of the public disliked it. It’s also far harder to see Krazy Kat‘s impact on the medium. One could argue that it is the least influential canonical work in comics, and perhaps that is even true for all artforms.

There is arguably no comic work as canonical as Krazy Kat. When The Comics Journal chose its greatest comics of the 20th Century, Herriman’s strip was #1. I’d distinguish slightly more, but the Sundays may be my favourite work ever in comics. But unlike other revered classic newspaper strips – say Little Nemo, Popeye, Pogo, Terry & the Pirates, Peanuts – it was never terribly popular; indeed, a lot of the public disliked it. It’s also far harder to see Krazy Kat‘s impact on the medium. One could argue that it is the least influential canonical work in comics, and perhaps that is even true for all artforms.

In this essay I want to look at some of the reasons for the lack of popularity and subsequent influence, which I think come from a few sources, particularly Herriman’s inimitable genius and the strangely indeterminate nature of much of the strip, which I think makes it a Modernist or even Postmodernist work worth serious consideration alongside the usual array of classic Modernist literature from the first half of the 20th Century.

Biography & Early Work

Biography & Early Work

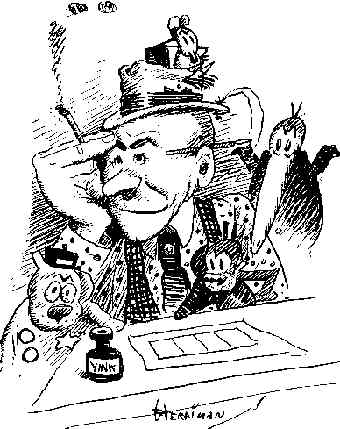

George Herriman was born on August 22nd 1880, in New Orleans, though his family moved to Los Angeles six years later. George moved to New York City in 1900, and his first cartoons appear in Judge magazine the following year, succeeded soon after by his first newspaper strips. His work soon gained some positive attention: as early as 1902, there is praise from Bookman: “Art combined with poetry,” they said, which is a comment that stayed true for the rest of his life.

There are hints of what was to come over the next several years: his first black cat appears in the Lariat Pete strip in 1903, and the first talking cat is two years later in Bud Smith. The next year the short-lived Zoo Zoo strip was his first to be centred around a cat. In 1909, several characters appear who are later found in Krazy‘s territory of Coconino County, the last two with slightly different names: Gooseberry Sprigg, Joe Stork, Dan Coyote and Cincho Pansy. The 1910 strip Dingbats features characters waxing lyrical in similar ways to the later work.

There are diversions in those years. In 1905, he moved back to LA, and became an editorial cartoonist and human-interest reporter. I particularly like a piece about a bullfight show in LA, where the toreadors addressed the governor of California in Spanish: “Although he admits his own Spanish is rather weak, Mr Herriman has translated the remarks to mean, roughly: ‘I and my desperate friends will now try to make money waving rags at this genial old cow.’” This reminds me strongly of some of Mark Twain’s travel reportage, especially one piece about French duelling.

He returned to NYC in 1910 and worked alongside such distinguished figures as Tad Dorgan, Rudolph Dirks (The Katzenjammer Kids), Winsor McCay (Little Nemo) and Cliff Sterrett (Polly And Her Pals). In 1913, he renamed The Digbat Family to The Family Upstairs, a strip about apartment life, a new subject then. The titular characters were never seen, but we did see their irritable mouse Ignatz, who tormented the Digbats’ wacky cat in a tiny strip at the bottom of the main strip. The vaudeville slapstick antics of these two characters moved into their own daily strip from October 28th 1913, entitled Krazy Kat, gaining a Sunday page from April 23rd 1916.

William Randolph Hearst loved it, but it shocked others (one newspaper editor termed it “this weird stuff nobody can understand”). He took it out of syndicated comics when NOBODY wanted the Sunday page on solicitation, and ordered it into his 9 papers. Editors were rebellious, and Hearst put it in the New York Journal’s drama & art section, rather than with the other comics. There were loads of letters of complaint from readers, and local editors objected. The page was pulled from local papers, and Hearst demanded its return. This went back and forth into the 1920s. A Saturday colour page appeared briefly in 1922 (for just 10 strips), in NYC only: the papers had better sales elsewhere without it, so this was soon dropped. Hearst gave Herriman a lifetime contract, which is surely the reason the strip continued for over 30 years.

But alongside this lack of popularity with the public, the fact is that the strip exploded into life when it gained a full page to play with and in: it developed from tiny vaudeville comedy skits into a world of its own, and we get the magical Coconino County with its shifting South-Western desert landscapes, vegetation and adobe homes, the symbolic nature of Ignatz’s bricks, and the growing cast of characters making up a society.

Plot & Characters

Plot & Characters

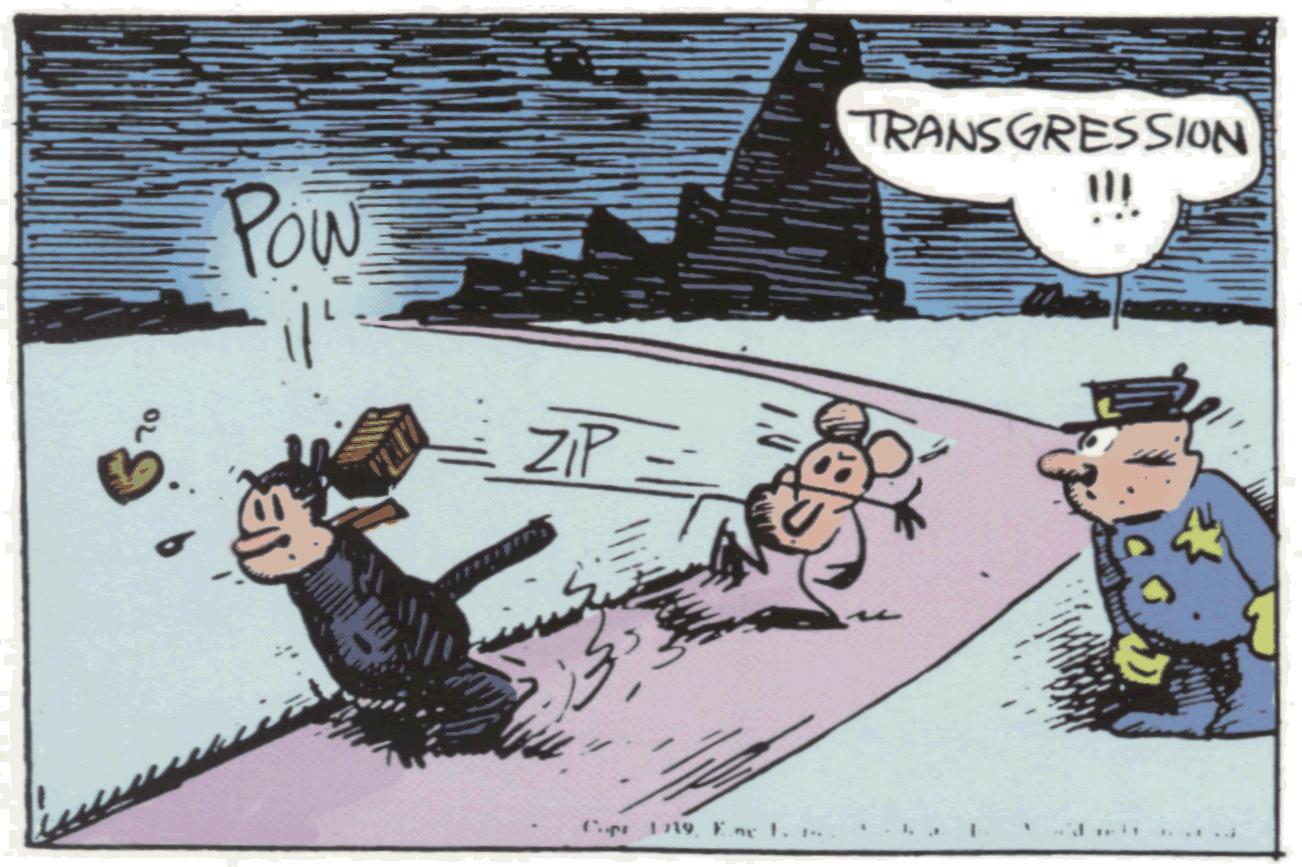

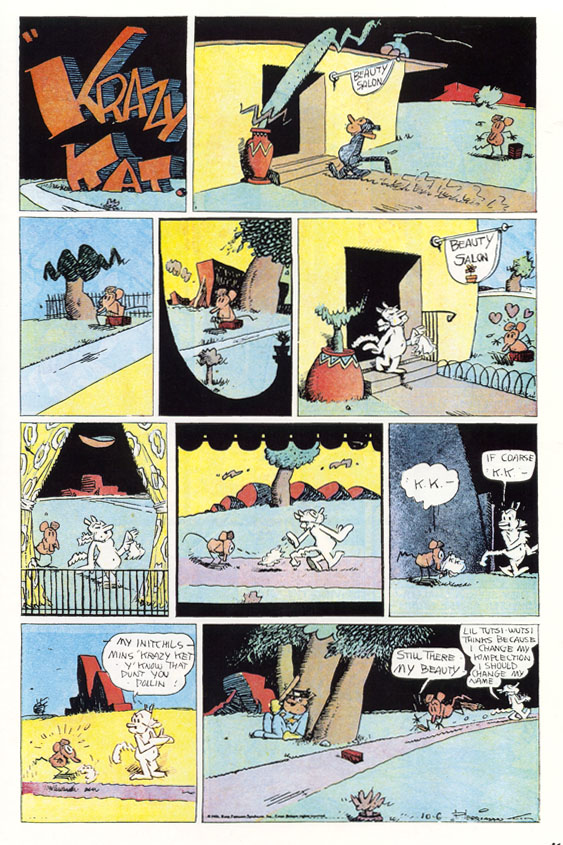

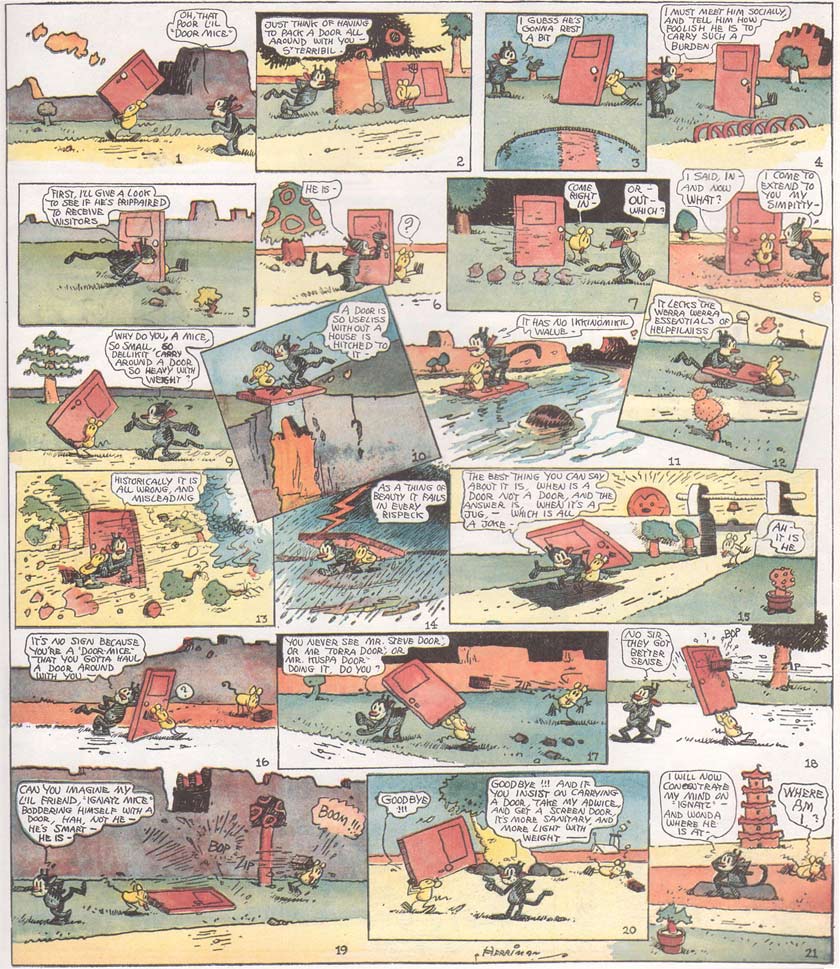

In case anyone isn’t familiar with the strip, I’ll explain the basics. Ignatz Mouse hates Krazy Kat, and expresses this by throwing bricks at the cat. Krazy interprets these attacks, because of race memory of some events in Ancient Egypt (where bricks were used as a delivery medium for love letters), as tokens of love. Offissa Pupp adores Krazy too, and sees the brick-throwing as simply a criminal assault, and locks Ignatz up. That really is the bulk of the story, which ran until Herriman’s death in 1944.

There are other characters, of course, among them: Kolin Kelly, a dog who makes bricks, so Ignatz is one of his best customers; Joe Stork, who delivers babies; Bum Bill Bee, “a pilgrim peregrinating the highway of dreams”; Don Kiyoti & Sancho Pansy; even Mari-Juana Pelona (there are plenty of references to the drug).

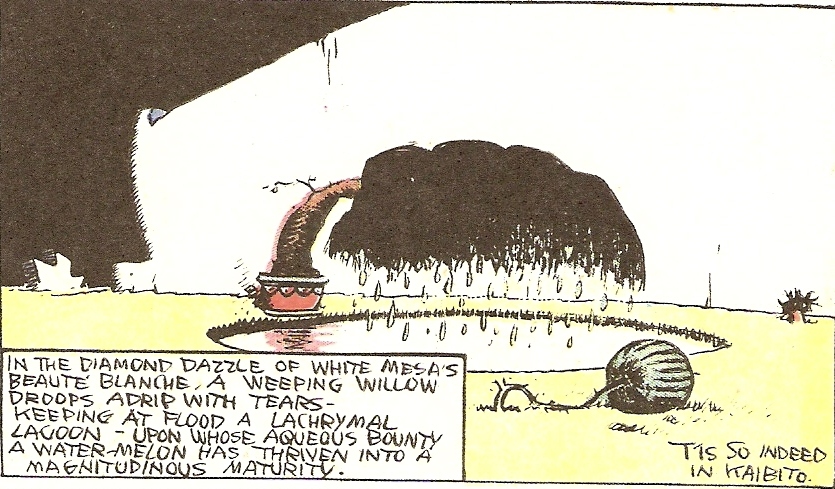

The setting is fascinating: the landscape is derived from Monument Valley, made most famous later in the movies of John Ford (who was shown the valley by locals who Herriman also knew). Herriman was a regular visitor to Arizona for decades, and used some real mesas alongside the more obviously fantastic formations. Plants, often even trees, tend to grow in pots in Coconino County: the pots look Navajo, another Arizona reference. There’s plenty of Spanish in the language too.

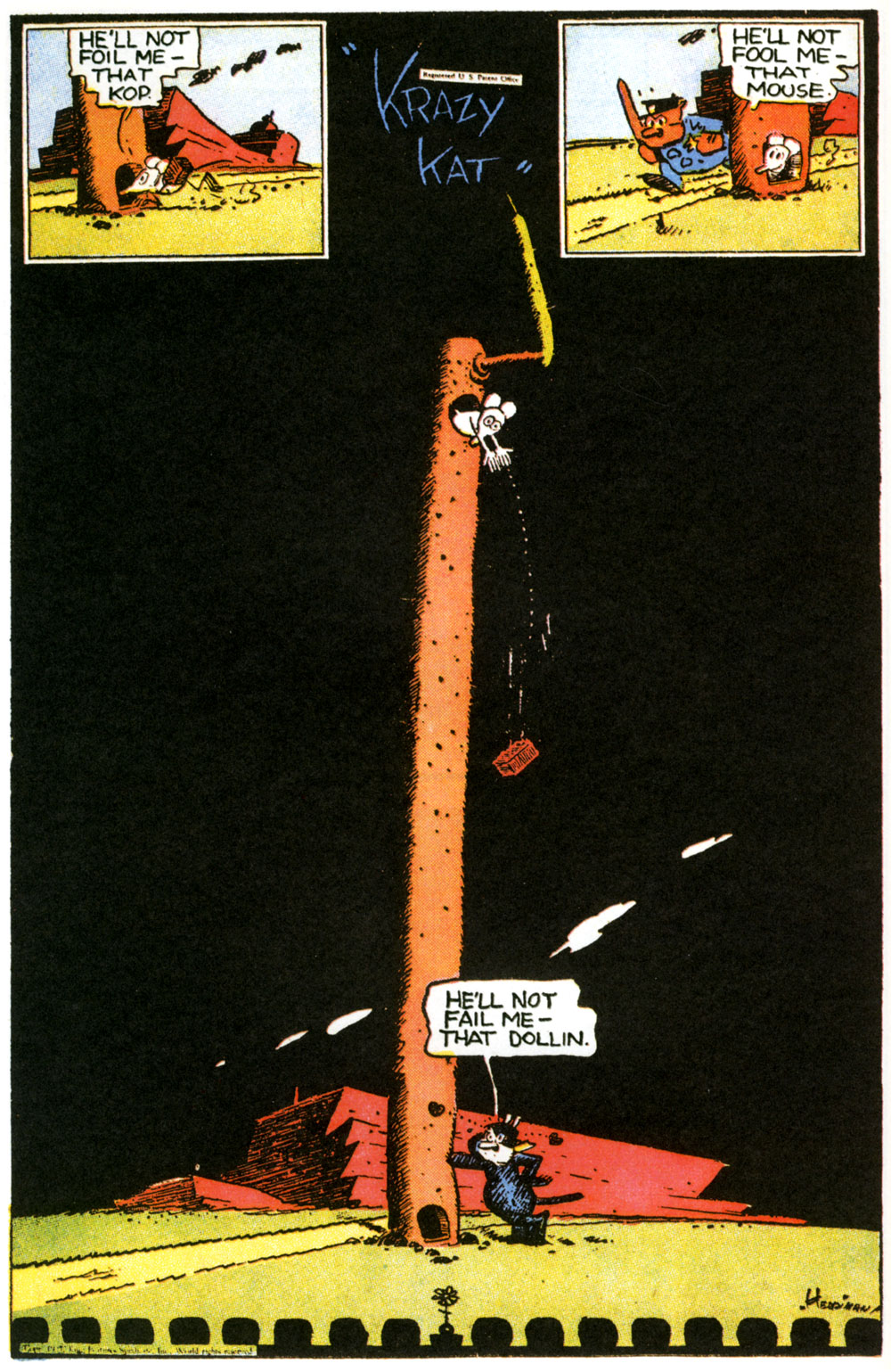

The most notable thing about the setting is the instability of the backgrounds – mountains, trees and buildings mutate from one panel to the next. This is a point I will return to.

Style & Reputation

Style & Reputation

Clearly the characters now read as archetypal: you can find the same cat/mouse/bulldog confrontations in Tom & Jerry. However, this wasn’t so then; I’ve seen claims that the first KK animation, in 1916, is also the first animated cat. It’s also worth noting that the animal nature of the characters is mostly irrelevant: it’s a character comedy rather than so much an animal one. In my more flippant and careless moods, I have been known to describe it as like Tom & Jerry if it had been written by James Joyce and illustrated by Pablo Picasso, but don’t quote me on that, as it’s silly.

But if the characters seem routine enough now, nothing else does. The style is not like any comic before or since. Gilbert Seldes (see later) says “it is our one work in the expressionistic mode” (“our” there means American, rather than the comics medium), and that Herriman displayed a “naïve sensibility rather like the douanier Rousseau.” I’m not entirely convinced by either claim – “expressionism” can be used for countless comics with just about as much justification, and I suspect the Rousseau comparison was an attempt to valorise the simplicity of comic strip drawing, since Seldes was claiming Krazy Kat as great art. Some surrealist artists claimed Krazy Kat as a work in their mode, and this has a little more foundation in the strip – the fluid setting, the unreal, sometimes dreamlike, events, and the use of language.

The language is absolutely extraordinary. Herriman was trilingual (he also spoke Spanish and French) and officially “creole” (another point I will return to), and in Krazy Kat he created what often sounds like a patois all its own, mixing, as Elisabeth Crocker identifies, “ethnic dialects, primarily New York Yiddish and Tex-Mex Spanish accents, combined with anachronistic syntax and literalized metaphors.” The result is often highly poetic: there’s an evocative beauty to lines pulled as subtitles of the Eclipse reprints of the Sunday strips: ‘The Limbo Of Useless Unconsciousness’, ‘Howling Among The Halls Of Night’, ‘Pilgrims On The Road To Nowhere’.

The language is absolutely extraordinary. Herriman was trilingual (he also spoke Spanish and French) and officially “creole” (another point I will return to), and in Krazy Kat he created what often sounds like a patois all its own, mixing, as Elisabeth Crocker identifies, “ethnic dialects, primarily New York Yiddish and Tex-Mex Spanish accents, combined with anachronistic syntax and literalized metaphors.” The result is often highly poetic: there’s an evocative beauty to lines pulled as subtitles of the Eclipse reprints of the Sunday strips: ‘The Limbo Of Useless Unconsciousness’, ‘Howling Among The Halls Of Night’, ‘Pilgrims On The Road To Nowhere’.

The layout of the strip was imaginative and original. The dailies stuck with a conventional sequence of panels across the strip, but the Sundays were far more varied, often formally like nothing before them. The drawing style appears to be spontaneous and loose, with everything looking a little rough and scratchy, as if inked in a hurry: in fact Herriman deliberately exaggerated that look by scratching off inked parts.

None of this really captures it, and I am making it sound as if it was an art project. In fact it was funny – Herriman’s gags and excellent comic timing mostly seem to derive from vaudeville, from Jewish comedy of the time; and he was a vivid cartoonist, with bouncy figures packed with life and energy. There are also other emotions in the strip, unusual in slapstick: the melancholy irony of Krazy yearning for a brick to the head and the different interpretations that the characters take from this. There is also humour in Krazy’s good-hearted naivety, often puncturing the pretensions and hypocrisies of other characters. There are also other descriptive terms that need to be worked in here: despite the violence at the heart of the plot, it’s a gentle, whimsical strip. It also seems to partake of the new jazz sound of the ’20s, in its rhythms, feel and language.

Despite its unpopularity with the masses, there was an intellectual element that loved the strip. Culture critic Gilbert Seldes’s The Seven Lively Arts (1924) pioneered appreciation of American popular culture, and helped a great deal in breaking down High/Low Art barriers. The book argued that various low art forms should be taken as seriously and admired as much as the established high arts: these lower forms included jazz, movies and vaudeville and, in a section centred on Krazy Kat, comic strips. Seldes called KK “the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today.”

There was a Krazy Kat ballet written in 1922 by John Alden Carpenter, with input from Herriman, who designed the costumes and rotating scenery. The music, apparently more jazz than classical, is still performed as part of Carpenter retrospectives – Seldes, incidentally, claimed that the only person who could have made a success of the lead role was Charlie Chaplin.

It was successful enough that there were several animated Krazy Kat series: I’ve mentioned the first, in 1916, then there was another attempt in 1920, and intermittently more short-run attempts through the ’20 and ’30s. It was revived in 1962-64 by King Features, mostly directed by Gene Deitch – I have several of these, and they don’t feel remotely like the strip.

It was fortunate that the ballet and critical adulation came along in the ’20s. Vanity Fair (then arguably America’s leading arts journal) added Herriman to their contemporary Hall of Fame, saying the strip was “comparable only to Alice in Wonderland”. This was needed, as Hearst’s interest shifted rather from his newspapers (and the importance of strips to these was gigantic) to movies, so Herriman’s main advocate and protector was less involved.

The strip also had a peerless collection of known fans. e.e. cummings wrote the introduction to the first ever collection. Picasso would insist that Gertrude Stein phoned him from America to read out the new strip every Sunday, after which she mailed it to him. Other notable fans then and since include writers James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, T.S Eliot, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Jack Kerouac and Umberto Eco, artists Willem de Kooning and Philip Guston, plus E.C. Segar, Walt Disney, H.L. Mencken, Charlie Chaplin, W.C. Fields, Woodrow Wilson and Quentin Tarantino (Samuel Jackson reluctantly dons a Krazy Kat t-shirt in Pulp Fiction). It has always pained me that Segar and Herriman adored each other’s work, but thought the other was so far above them that they were each too shy to get in touch.

Modernism & Meanings

Modernism is a tricky concept: it’s generally billed as a reaction to the end of the certainties and absolute truths of previous times, particularly religion and the Enlightenment. Writers talk of a ‘project’ to find a new way, not reliant on undermined ideas of the past. But the idea that Modernists – in art, literature and elsewhere – were seeking some new, true way is not terribly well founded. Yes, some artists and groups of artists issued manifestos, but this was not universal, and was far more rare among novelists and poets.

Also, comics started alongside Modernism, so had no premodernist work against which to react. They were almost never realistic from the beginning, and were nowhere near being part of any High Art movements. It’s therefore easy to overreact to elements of the fantastic – always a commonplace in comics, of course – or to poetic elements, perhaps because it’s such a shock coming across them in a form almost always low on lyricism.

Nonetheless, Krazy Kat looks and reads as something different from the other comics of the time, in ways that seem to have something to do with Modernist currents and movements, and even, arguably, prefiguring elements of Postmodernism, which is usually constructed as a reaction against the failure of Modernism to find some new true way, embracing instability and uncertainty instead.

In the wider world, the older certainties were damaged by science: evolution, psychology, relativity. Humanity was no longer so distinct from the rest of the natural world; our thoughts were more complex and less knowable that had been assumed; and the universe was low on absolutes, even time and space being relative, contingent.

If we are to take those breakthroughs as provoking the crisis leading to modernism, maybe we can cite some later ones as relating to postmodernism: quantum physics and Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, plus Godel’s incompleteness theorems. The universe was not something that we were going to be able to pin down deterministically, because it had core elements of randomness and indeterminacy, and Godel showed the impossibility of completely proving mathematics.

The Uncertainty Principle seems particularly of interest when thinking of Herriman’s work, for various reasons. Firstly I want to return to Herriman’s “creole” status. In the 1880 census, both of Herriman’s parents were recorded as “mulattoes”, i.e. of mixed race, so Herriman was officially “coloured”. He always declined to talk about this heritage, and there is one photo showing that his ever-present hat was hiding tight black curls. His first continuing character was Musical Mose, a black musician who tries to impersonate other races for gigs – but is always exposed. It may be unwise to put too much weight on this, but a strip about ‘passing’ for some other race may reflect his own life. It’s also worth drawing out because arguably the most revered cartoonist in the history of the form was not white – black artists do tend to be marginalised at times, and we ought to react against this.

But how does this relate to Krazy Kat? We could draw parallels with the racism art spiegelman expresses via animals in Maus, but more broadly Elisabeth Crocker says that “Herriman couched his assertions about the socially-constructed nature of categories like race and gender, as well as categories such as class, age, ethnicity, and occupation, so deeply in the sophisticated allegory of his comic strip, however, that few readers noticed them.” She points out that Krazy is black, and Ignatz is a very Jewish name (as are his son’s names: Irving, Marshall and Milton). In one strip, Krazy is dyed white, and Crocker says, “Ignatz cannot recognize Krazy when Krazy is white; whiteness in itself is for Ignatz an appropriate object of erotic desire, which then in turn must be feminine.” Indeed, Ignatz is positively attracted to this white cat. Obviously this can be read simply as mistaken identity comedy, but it’s certainly hard to dismiss Crocker’s analysis, which also applies to the next area of indeterminacy. There is at least one strip where Ignatz is covered with soot, becoming black, and Krazy’s attitude changes just as dramatically.

But how does this relate to Krazy Kat? We could draw parallels with the racism art spiegelman expresses via animals in Maus, but more broadly Elisabeth Crocker says that “Herriman couched his assertions about the socially-constructed nature of categories like race and gender, as well as categories such as class, age, ethnicity, and occupation, so deeply in the sophisticated allegory of his comic strip, however, that few readers noticed them.” She points out that Krazy is black, and Ignatz is a very Jewish name (as are his son’s names: Irving, Marshall and Milton). In one strip, Krazy is dyed white, and Crocker says, “Ignatz cannot recognize Krazy when Krazy is white; whiteness in itself is for Ignatz an appropriate object of erotic desire, which then in turn must be feminine.” Indeed, Ignatz is positively attracted to this white cat. Obviously this can be read simply as mistaken identity comedy, but it’s certainly hard to dismiss Crocker’s analysis, which also applies to the next area of indeterminacy. There is at least one strip where Ignatz is covered with soot, becoming black, and Krazy’s attitude changes just as dramatically.

Even more interesting, and certainly clearer, is ambiguity about sex: Krazy generally relates to and is related to by both Ignatz and Offissa Pupp as a female, but this is indeterminate. Male pronouns are used for Krazy nearly as often as female ones. Alec Findlay claimed that “Herriman said that Krazy was willing to assume either sex should the need actually arise.” This was certainly not carelessness or a basic lack of continuity, but a completely deliberate indeterminacy: Krazy at one point says, “I don’t know whether to take unto myself a ‘wife’ or a ‘husband’.” The strip on December 17th 1922 is particularly explicit in this, wherein Dr Y. Zowl questions Krazy, asking whether the lady of the house is in, then whether the gentleman of the house is in, getting positive answers to both, after which Krazy points out that he/she is the only one in. It’s hard to resist parallels with quantum physics here, where electrons can be particles or waves depending on what the observer is trying to discover, and this again reflects what Crocker says about the socially-constructed nature of gender. At a stretch, we might claim that he was deconstructing ideas about race and sex…

As previously mentioned, the background of the strip is similarly indeterminate, the landscape and buildings changing from one panel to the next – I have seen attempts to claim that we are borrowing Krazy’s perceptions, but I can’t see that as a feasible explanation. Crocker says that “The perpetual motion of Coconino, a city pretending to be a desert, epitomizes the perpetual ideological and perceptual adjustments that the urban subject must make in order to naturalize the city environment.” I’m not so sure about this, but it’s unquestionably an overtly anti-realist move.

The language of the strip reads more like that of Joyce than that of any other comic writer: the demotic poetics, words from multiple languages and dialects, the strangeness and the extensive wordplay and punning. This isn’t just a writer’s joking around – a failure to understand each other is basic to the brick-throwing centre of the whole strip, and Krazy says in one strip that “lenguage is, that we may mis-unda-stend each udda.”

Herriman also played with the form – in one 1919 strip, Ignatz points out that “We’ve been in the paper all the time.” It’s probably not worth making too much of this – the form was new and in development, and many cartoonists were highly conscious of the boundaries of the medium, and featured such playfulness, perhaps first seen in painting in Magritte’s famous 1928 “Ceci n’est pas une pipe”. Nonetheless, the breaking of any illusion of straight representation has a postmodernist flavour.

Influence

Influence

There are two directions here: where did this extraordinary strip come from, and who has it affected in the decades since?

To be honest, the first is largely guesswork – despite Seldes’s efforts, comic strips were not taken so seriously that there are in-depth interviews with Herriman. We know a few things: his favourite writer was Dickens, but I can’t see a lot of him in Krazy Kat; he was a big Mack Sennett fan, and there is a rave review in Krazy’s voice of The Gold Rush, but I think Krazy’s slapstick probably owes much more to vaudeville than silent movies, though perhaps Chaplin and characters like Micawber can be seen as influences on some of the characters (as can Don Quixote); there is design work unmistakeably linked to South-Western Native America designs; and I have mentioned the impact Monument Valley had on the Coconino landscape. There are some similarities to Kipling, both in specific reference to stories like “The Cat Who Walked By Himself” and in the parable style of some early strips, rather like the Just So Stories. It’s hard to resist calling some of his wordplay Joycean (I especially like the ambiguity of the final word in “You turn off the light and turn on the dark, you turn off the dark and turn on the light — positivilly marvillainous”), but this occurs in Krazy Kat before Ulysses was published, and long before Finnegans Wake, and the similarities are generally pretty superficial.

Jon Carroll, in the San Fran Chronicle, says Krazy Kat “is to comic strips what Chuck Berry is to rock and roll.” This implies a vast and pervasive influence on succeeding generations, but this is very hard to pin down. He worked with Cliff Sterrett from before either Krazy Kat or Polly and Her Pals started, and it’s hard to know how much Sterrett’s stunning use of modern art techniques in his strip had to do with Herriman – very possibly nothing at all.

In the most general sense, we could claim that Felix the Cat derived from Krazy, indeed that all dog/cat/mouse comedy since (we’ve mentioned Tom & Jerry) trace back to this, but it’s not the basic set of funny animals that makes Krazy Kat great, so this isn’t a terribly interesting line to pursue, however much truth there is in it. Kerouac said that Krazy Kat was an immediate progenitor of the Beat Generation, which is a nice line, but any influence is less than clear. I’ve seen claims that the terrain of Chuck Jones’s brilliant Roadrunner cartoons comes from Herriman’s work, but this is both unclear and of little interest; however, arguably the baroque complexity of some of Ignatz’s means for delivering the brick have rather more to do with Wile E. Coyote’s haplessly complicated ploys.

Lots of great cartoonists have claimed Herriman’s work as an influence and inspiration – Charles Schulz, Bill Watterson, Will Eisner, Jules Feiffer – but again, it’s not at all obvious from looking at their work that there is any connection (perhaps occasionally the free layout of Sunday Calvin & Hobbes strips, but this feels like far too big a stretch).

There are a few clear cases where there is a more direct effect, none of them comic artists: the artist whose work most reminds me of Herriman’s is Javier Mariscal, best known for his Barcelona Olympic mascot, Cobi. Novelist Jay Cantor wrote a novel in 1988 called Krazy Kat, using the characters for commentary on nukes, turning Herriman’s wordplay into more literally Joycean puns, political rather than poetic: ‘keepitallism’. (Cantor also fixes Krazy’s sex as female, and lamely claims that the shifting landscape was “the light playing tricks”: disappointing regressions to the fixed and literal to find in a Postmodernist reworking.) When I first saw the work of the wonderful British painter Fiona Rae, I claimed I saw a Herriman influence, to derision from friends, who reasonably saw Miro instead – and then a year or two later she wrote a short piece in The Guardian about her love for Krazy Kat, so I felt vindicated.

So why is the greatest ever work in comics not a big influence on subsequent comics? In fact, I’d claim this is a good thing: there is a certain kind of genius where imitation cannot work. The one strip I’d rank somewhere alongside Krazy Kat would be Segar’s Popeye dailies, and this was a gigantic influence, almost too pervasive to be disentangled since – his storytelling was exemplary, something anyone and everyone could and did learn from. I don’t see Herriman’s work the same way: copying his kinds of drawing, layout and storytelling would almost certainly be a disastrous flop for anyone else, any artist not having his distinctive brilliance.

This is even more true of his writing: I suspect a lot of his linguistic flair is partly due to his creole upbringing, the mix of languages with which he grew up, something available to very few. The painful results of lesser writers trying to copy Alan Moore’s more extravagantly purple writing is a lesson here: thankfully Herriman’s more dazzling lyricism seems to have been far enough beyond that that other writers haven’t even tried to imitate it.

I think it’s his uniqueness and unmistakeable genius that makes him inimitable, that mean a revered strip that ran for over thirty years is such a small influence on the medium: unlike other giants like Crane, Segar, Caniff, Kirby and so on, novices could not take lessons from Herriman with results that produced any improvement in their work. This is perhaps no bad thing, though it’s a shame that the extravagantly personal work didn’t seem to make room for others to be as far from the mainstream, but I suppose the lack of commercial success is part of that. Why follow someone into outre territory when the move wasn’t popular, and why would newspapers want another strip that so many readers disliked?

When George Herriman died, of cirrhosis of the liver, on April 25th 1944, Krazy Kat was running in just two newspapers, and without the contract for life that Hearst had given him, it seems likely that it wouldn’t have lasted so long. I’ve never seen any evidence that there was any consideration given to appointing a new cartoonist to take over, which is a relief, but shows its low standing at the time. (There was a later comic book revival, from Dell in the 1950s, with the great John Stanley writing and drawing the first five comics, but this bears no real resemblance to Herriman’s work.)

Links

The Elisabeth Crocker essay mentioned several times above.

The chapter on Krazy Kat from Gilbert Seldes’ The Seven Lively Arts.

A short piece by me partly about KK on Freaky Trigger.

Tags: George Herriman, Krazy Kat, newspaper strips

Fine piece of work, Martin!

RE: literary influence of/reference to Krazy Kat

Beyond Cantor, there’s Jonathan Lethem’s story “Five Fucks” (later bowdlerized to “Five” when anthologized, though I can’t remember where) included in his story collection THE WALL OF THE SKY, THE WALL OF THE EYE. It’s not brilliant but a neat experiment, playing with the Krazy Kat love triangle in quite a nifty way.

Good piece, Martin.

After Captain Beefheart’s recent, tragic death, I wonder if there’s a comparison to be made between him and Herriman. For now at least, let’s concentrate on how the two are received. Many people, (a href=http://andrewhickey.info/2010/12/18/beefheart/> for example here, commented how musically conservative acts such as Oasis would name-check him to sound cool, but this was at the expense of actually engaging with his music. The picture is of something too outre to actually get into, to revere without really liking.

Meanwhile the bands who were truly influenced by him took that influence at a deeper level, they didn’t actually sound a whole lot like him.

It seems to me Herriman is similarly treated.

Also, while Modernism was undoubtedly a reaction to new uncertainties, I’m not sure how much I see it as a project to find a new true way. Perhaps that’s true of certain Modernist movements, such as Constructivism, but it hardly fits Dadaism for example.

I tend to see Modernism as the end of pseudo-objectivity in art. The artist’s role became to paint what they see, not what they suppose to be there. I’d also suggest Modernism was more influenced by political events than scientific, but that’s perhaps an argument for another time.

Well yes, as I say, I think the claim that Modernism was seeking a new true way is dubious – but even the Dadaists were inclined to manifestos claiming their approach was the only correct one for the age, so it’s not a completely silly perspective. The silliness comes with talking of Modernism as a whole as a project, I think – clearly the Constructivists and Dadaists were not working on one project, let alone Modernist writers, musicians and so forth.

As for pseudo-objectivity, that depends where you start Modernism – the Impressionists were certainly claiming their art was a more accurate representation of what we see, for instance. Some Modernist novelists would probably have claimed that they were more truly representing how people were, how they thought.

I’d be interested in your political line on this. I think I should have mentioned Marxism along with the scientific points – again, that undermined the old certainties of who should be in charge.

It is ill-fitting to see Modernism as a whole project. It was on the whole incredibly fractuous, for one thing. But then again only rivals argue that much, and rivals tend to have something underlying in common…

Yeah, but “what we see” is the vital phrase. We may know that the bridge across the lily pond is solid iron, but look at it a certain way and it looks like it’s just made out of flecks of light.

…all of which has an impact upon the political. In one sense it suggests the world isn’t fixed and immutable, that it can be reworked just like art can be reworked. It also suggests that there’s worlds inside your head, waiting to get out.

But in practise there comes to be a tension between the two. Is art about getting your subjectivity out and on paper, in which case it’s inherently about the individual? Or is it a collective enterprise, blueprints for a future society? Expressionism and Constructivism probably represent the two sides, but that tension seems to me almost inherent in Modernism.

Fascinating ariticle on something that I knew of but knew nothing about.

It was interesting to see the reversal of the usual situation whereby something which is very popular is nevertheless cancelled simply because someone on the top floor does not like it (and yes, I was thinking of Michael Grade when I typed that, but there are other examples).

With regards to the 1916 film, would that also make Krazy Kat the first comic related adaptation for the (big) screen ?

Definitely not, as Rich Johnston points out here: http://www.bleedingcool.com/2010/09/09/the-very-first-comics-to-film-adaptation-larroseur-arrose-from-1895/.

I’m not sure what the first animation based on comics was, but Winsor McCay made a Little Nemo short as early as 1911, so certainly well before Krazy.

Blimey ! The educational aspects just keep flowing. Thank you for the update, Martin, much appreciated.

“Male pronouns are used for Krazy nearly as often as female ones” – surely there are many, many, many more references to Krazy as “he” throughout the strips life? Isn’t it quite rare to find a ‘she’? I’ve always thought of Krazy as male, without a shadow of doubt.

Don’t forget Herriman’s illustrations for Don Marquis’ “Archy and Mehitabel”. Marquis’ language and outlook has the Herriman feel to it.

I thoroughly enjoyed your article. Cheers,

Simon.

I would have thought it was about even – I think I got the idea that female pronouns slightly dominate from somewhere else. There are certainly a lot of both cases – the female pronoun is certainly not at all rare.

Martin, that is just not correct. I’ve now spent several happy hours combing Krazy Kat editions. I went through the Eclipse editions from 1916 – 1924; I went through the Fantagraphics volumes from 1939 – 1944; I double checked the Tiger Tea episodes; I went through my own collection of the dailies right across several decades. No ‘she’, no ‘her’. But lots and lots of ‘him’, ‘his’, ‘himself’, ‘he’, along with ‘Mr Krazy Kat’, ‘senor’, ‘uncle Krazy’, ‘good boy’, ‘king’, ‘nephew’, and ‘sir’. Whenever Herriman refers to his own creation within the strip, he uses ‘he’. Even if you can find any female pronouns at all across the whole canon, by my research it would certainly put them in the minority. See for yourself. The good thing about doing such research is that it’s highly enjoyable in this particular case.

You surprise me – I can’t check as I am at work, but I’ll spend a few minutes looking around when I get home.

I think it’ll take more than a few minutes, Martin. I spent at least five hours, for the sake of accuracy!

Nice article. There’s far too little written on Herriman so I always welcome pieces like this. I will say, though, that I always had the impression that Krazy Kat was reasonably popular for at least a few years. There were licensed dolls and cartoons and such, and I recently stumbled across a Krazy Kat cameo in a Harold Lloyd feature.

Yes, I may have overstated that a little – it was disliked by a lot of people, editors and public, and for a strip that ran and was given such space in a lot of major papers for so long, it wasn’t a popular hit. I can’t imagine there has been another strip that ran for 30 years in major syndication with so little popular affection, and so much outright dislike. It got a lot of bad reaction again in the UK when The Guardian ran some ancient dailies for a while, which I guess was around 20 years ago.

Martin, I continue to anticipate the results of your checking out of the Krazy gender issue, if only for the sake of closure. Meanwhile, I’ve now gone through all of the Sundays, every one of them. No ‘she’. No ‘her’.

All the best,

Simon.

Martin – silence is golden.

Ha, sorry – I’m afraid I’ve been really ill since before Xmas, and just managing to keep this site ticking over. I hope I will get to looking back through some KK Sundays soon, but no promises until I start feeling better, which could be some time yet, unfortunately.

Sorry to hear that. Get well soon and all the very best.

Because I know you are still checking this 3 years later, Herriman himself often says Krazy has no gender, being more of a sprite or imp.

[…] Krazy Kat: Modernism and Influence […]

[…] Michael. “Krazy Kat: Modernism and Influence.“ FA the Comiczine. Accessed […]

[…] Krazy Kat – Often considered the most “literary” of the early comic strips. Here’s a great article about it. When looking at Crazy Ket pay special attention to the layout as well as use of language. Gilbert […]

[…] and art critics for more than 80 years. ( from wikipedia ) I recommend to look at these 2 ( one / two ) articles about […]