‘In our midst … an immortal!’ Hercules in 1960s Marvel comics

by Tony Keen 19-Jun-22

In the 1960s Marvel introduced the Greek mythological hero Hercules, first in Thor, and then in the Avengers. But he never quite took off.

Hercules takes on Ares, God of War, from Avengers #38 (March 1967). Script by Roy Thomas, art by Don Heck and George Bell.

Hercules was quite an early arrival in the Marvel Universe, first appearing in 1965, and being an Avenger by 1967. Yet, despite being described as ‘the surprise Marvel sensation of 1967’, he has never quite been as big a presence as one might expect, given how culturally visible he is in other media. In this article, I’ll look at Herc’s early Marvel years, and suggest some reasons for his lack of impact.

The mythological demi-god Hercules, the better-known Roman name for the Greek Heracles, was the strongest hero of Greco-Roman mythology. Others, such as Perseus or Achilles, might have been the son of this god or the other, but only Hercules possessed true superhuman strength. Hercules alone of the heroes was an actual demi-god, and enrolled amongst the gods on his death. Greek kings such as Alexander the Great and Roman emperors such as Commodus modelled themselves upon Heracles/Hercules. Representations of Hercules and his exploits were found throughout the Roman world. An example is the Farnese Hercules, a Roman marble statue that copies a Greek original, and shows a resting Hercules, leaning on his club, over which is draped the skin he took from the Nemean Lion when he killed it. In his hand, hidden behind his back, he holds the golden apples that he took from the Garden of the Hesperides, daughters of the Titan Atlas. The club and the lionskin were Hercules’ typical attributes; he was also muscular, and often bearded. Hercules continued to be often represented into the post-Roman period; for instance, Antonio del Pollaiuolo’s Hercules and the Hydra of c. 1475. Hercules is still an important figure in popular culture, as demonstrated by two Hercules movies in 2014, Hercules starring Dwayne Johnson, and the rather less good Legend of Hercules.

The ancient mythological heroes, especially Hercules, have often been linked to the modern superhero, who debuted (notwithstanding arguable antecedents such as the Shadow, the Spider, and Mandrake the Magician) with Superman in Action Comics #1 (June 1938). Hercules has been described as the original superhero; this connection is explicit in the title of Wendy Haslem, Angela Ndalianis and Chris Mackie’s 2007 edited collection, Super/Heroes: From Hercules to Superman.

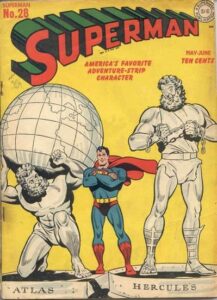

It is not, therefore, surprising that Hercules has featured in superhero comics almost from their inception. Superman was already described as ‘a modern-day Hercules’ as early as Action Comics #7 (December 1938). Superman #28 (May-June 1944) has a cover by Wayne Boring, showing Superman standing between larger-than-life statues of Atlas (the Titan doomed to hold up the heavens, often shown, as here, supporting a globe) and Hercules, shown holding a chain. Both statues seem to be alive, as they are shown looking, in some wonderment, at Superman. Insides this issue there is ‘Stand-in for Hercules!’, a story credited to Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster, but actually by Bill Finger and Ira Yarbrough. In this, a Mr Boyle reveals that all of the exploits of Hercules were in fact carried out by Superman. Since he tells this tale at a meeting of the Liars’ Club, one suspects that the reader isn’t meant to take it seriously.

It is not, therefore, surprising that Hercules has featured in superhero comics almost from their inception. Superman was already described as ‘a modern-day Hercules’ as early as Action Comics #7 (December 1938). Superman #28 (May-June 1944) has a cover by Wayne Boring, showing Superman standing between larger-than-life statues of Atlas (the Titan doomed to hold up the heavens, often shown, as here, supporting a globe) and Hercules, shown holding a chain. Both statues seem to be alive, as they are shown looking, in some wonderment, at Superman. Insides this issue there is ‘Stand-in for Hercules!’, a story credited to Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster, but actually by Bill Finger and Ira Yarbrough. In this, a Mr Boyle reveals that all of the exploits of Hercules were in fact carried out by Superman. Since he tells this tale at a meeting of the Liars’ Club, one suspects that the reader isn’t meant to take it seriously.

Other Golden Age comics made use of Hercules. In Fawcett’s Superman clone, the original Captain Marvel, Hercules one of the mythological figures who gives Captain Marvel his powers. Hercules provides the ‘H’ in the magic word ‘Shazam!’, and is the source of Captain Marvel’s strength.

A less benign side of Hercules is shown in early Wonder Woman stories, created by William Moulton Marston and Harry Peter, and published by National-DC’s sister company All-American. Hercules is important to Wonder Woman’s origin story; a lion-skinned Hercules, carrying his club, deceives the Amazon Queen Hippolyta, steals her girdle and enslaves the Amazons. The story is told in prose form in All-Star Comics #8 (December 1941-January 1942), and in expanded comics form in Wonder Woman #1 (Summer 1942). Despite Hercules’ presentation here as an antagonist, Wonder Woman still was described as having the strength of Hercules, first in Sensation Comics 2 (February 1942). When Robert Kanigher rewrote Wonder Woman’s origin in Wonder Woman #105 (April 1959), and perhaps drawing upon Captain Marvel’s backstory, he literalised this, making Hercules one of the gods who granted power (in this case, strength) to Princess Diana.

Three strips that debuted in 1940 all have Hercules as the lead figure. Created by Arnold Hicks, the Hercules of Timely’s Mystic Comics #3 (June 1940) was Hercules David, raised as a perfect physical and mental human on an Arctic island, away from civilization. When his father died, he was rescued and taken to America by two circus owners, who nicknamed him ‘Hercules’ (in a 2009 retcon in the Marvel Mystery Handbook we find out that his father called him ‘Varen’, a name not given in the original strips). He appeared just once more. Also in June 1940, in another of their titles, Daring Mystery Comics #5, Timely printed Little Hercules, the creation of Bud Sagendorf. Little Hercules was a twelve-year-old boy genius, who also had superhuman strength. He never appeared again.

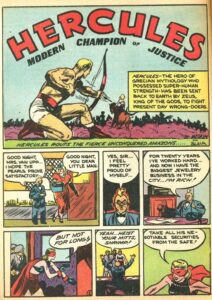

Hercules, Modern Champion of Justice was a feature in MLJ’s Blue Ribbon Comics from #5 (July 1940) to 8 (January 1941), the creation of Joe Blair and Elmer Wexler. He actually was the mythological demi-god, but now fighting crime in modern America. His final story, ‘Hercules fights the fierce unconquered Amazons’, took a very different view of the clash between Hercules and the Amazons from that shown by Marston and Peter almost a year later.

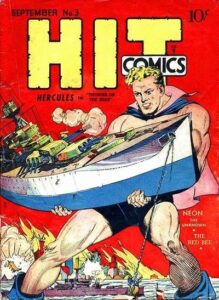

Hit Comics #3 (September 1940). Despite the cover’s implication, Joe Hercules couldn’t actually grow to giant size.

The longest-running 1940 Hercules was that to be found in Quality’s Hit Comics, who first appeared in #1 (July 1940), and continued to feature until #7 (January 1941). Like Timely’s Hercules, Joe had no connection to the demi-god other than the name, and was simply a circus strong-man who decided to fight crime after a banker drove his mother to a fatal heart attack. Joe Hercules’ debut story was credited to Dan Enloz, who was Dan Zolnerowich, though it is unclear if he wrote the story as well as drew it.

As most readers of this website will know, superheroes were very popular in the late 1930s and early 1940s. But after the end of the Second World War, their popularity declined rapidly, and by the mid-1950s, only Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman were still being published. Then in 1956, DC editor Julius Schwartz revived the superhero with a new version of the Flash, followed by in 1959 by a new Green Lantern, and in 1960, a superhero team, the Justice League of America.

One of DC’s main rivals was the company owned by publisher Martin Goodman. This had spent some time in the 1940s being Timely Comics, had become Atlas in the 1950s, and in 1961 renamed itself Marvel. Atlas has spent much of the 1950s dealing in science fiction and monster comics, produced largely by writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby. In 1961 Marvel got back into the superhero business, as Lee and Kirby, and other collaborators such as Steve Ditko, created the Fantastic Four, the Hulk, and Spider-Man, among others.

Timely and Atlas had published superheroic comics with a Greco-Roman mythological character at their centre. Kirby had created Mercury in the 20th Century for Red Raven Comics #1 (August 1940), subsequently reworking the strip as Hurricane, Master of Speed for Captain America Comics, where it ran from #1 (March 1941) until #11 (February 1942), though not with Kirby after the first two stories. (Both Mercury and Hurricane were subsequently retconned as identities used by the Eternal Makkari.) Then, from August 1948 to April 1952, Atlas published nineteen issues of Venus. Described by Will Morgan as ‘one of the strangest series ever published’, Venus began as a ‘funny career girl’ comic à la Millie the Model, then morphed into romance, chucked in some elements of superheroics, and then science fiction, and ended up as a horror comic.

However, when 1960s Marvel first introduced a mythological character, he was not drawn from Greco-Roman myth, but from Norse mythology. That was, of course, the Mighty Thor, a Norse god done as a superhero, the idea of Lee or Kirby, depending on whose account you read (I find Kirby’s more plausible). It was through Thor that Hercules would be introduced into the Marvel Universe. Though Lee and Kirby had brought back characters from the 1940s, such as the Sub-Mariner and Captain America, there appears (understandably) to have been no interest in reviving either Hercules David, or Little Hercules, and instead they recreated the character.

Lee’s first attempt to bring back Hercules in Marvel also turned out to be a non-starter. In Avengers #10 (November 1964), Immortus, the Master of Time, summons an opponent for Thor from history. That opponent is Hercules. Thor, of course, manages to beat Hercules. Here, Hercules carries his club (though he soon discards it), and is muscular. But he is clean-shaven, and wearing nothing but a pair of swimming shorts. He resembles the sort of body-builder made famous by Charles Atlas. A subsequent retcon in the late 1990s suggested that this Hercules was in fact a Space Phantom impersonating Hercules

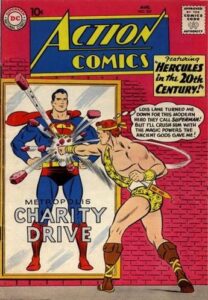

It should be noted that, shortly before this time, Hercules had become a recurring character over at DC, first appearing in a Superboy story in Adventure Comics #259 (February 1959). Here he teamed up with the Biblical Samson and travelled forwards in time to Smallville, to discover the secret of Superboy’s invulnerability. Then, decades later in comics time, but only just over a year in terms of publication, Lex Luthor brought Hercules from the past to fight Superman, in Action Comics #267 (August 1960). Hercules in the end aided Superman against Luthor, but then fell in love with Lois Lane (of course), and tried to put Superman to sleep for 100 years (Action Comics #268, September 1968). He returned in Action #279 (August 1961), but only in an ‘Imaginary Tale’, where he and his buddy Samson get engaged to Lois Lane and Lana Lang, respectively. In Action #308 (January 1964), Superman encounters a parallel-world Hercules, who is a giant, and looks nothing like the Hercules previously seen. Then in Action #320 (January 1965), Superman calls upon heroes he has already met, Hercules, Samson and Atlas for assistance, only to find he has accidently drawn them from another (!) parallel world, where they are all bad guys. Given that shared continuity across DC’s comics at this point was rather more notional than it later became, it is hard to suggest any direct link between Superman’s Hercules and that to be found in the pages of Wonder Woman.

It should be noted that, shortly before this time, Hercules had become a recurring character over at DC, first appearing in a Superboy story in Adventure Comics #259 (February 1959). Here he teamed up with the Biblical Samson and travelled forwards in time to Smallville, to discover the secret of Superboy’s invulnerability. Then, decades later in comics time, but only just over a year in terms of publication, Lex Luthor brought Hercules from the past to fight Superman, in Action Comics #267 (August 1960). Hercules in the end aided Superman against Luthor, but then fell in love with Lois Lane (of course), and tried to put Superman to sleep for 100 years (Action Comics #268, September 1968). He returned in Action #279 (August 1961), but only in an ‘Imaginary Tale’, where he and his buddy Samson get engaged to Lois Lane and Lana Lang, respectively. In Action #308 (January 1964), Superman encounters a parallel-world Hercules, who is a giant, and looks nothing like the Hercules previously seen. Then in Action #320 (January 1965), Superman calls upon heroes he has already met, Hercules, Samson and Atlas for assistance, only to find he has accidently drawn them from another (!) parallel world, where they are all bad guys. Given that shared continuity across DC’s comics at this point was rather more notional than it later became, it is hard to suggest any direct link between Superman’s Hercules and that to be found in the pages of Wonder Woman.

Superman’s Hercules also looked like a body builder. Rather than a lionskin, he wore leopard-print shorts (something Charles Atlas and other bodybuilders often did), and a leopard-print off the shoulder tunic. His red hair was tied in a fillet (as was the hair of the Hercules of Avengers). Frankly, he looked rather camp.

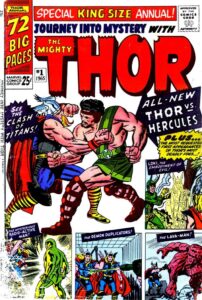

The reason the Hercules of the Avengers story had eventually to be retconned was that he was very quickly forgotten in mainstream Marvel continuity. In August 1965, Jack Kirby (with Lee scripting) had introduced a new Marvel Hercules, in Journey into Mystery Annual #1. This was the ‘real’ Hercules, very definitely the demi-god, as he is first met by Thor in Olympus, in a story that is set long before the time of Thor’s monthly adventures; there is even a brief appearance by Zeus. Jack Kirby’s wider engagement with mythology had already been demonstrated by the Tales of Asgard back-up strip that first appeared in Journey into Mystery #97 (October 1963), which adapted Norse mythology into comics form. The encounter with Hercules reads very much like a Tales of Asgard story, except that it does not take place in Asgard, or any other Norse mythological setting. Kirby had worked with Classical mythology in the past (Mercury in the 20th Century has already been mentioned), and would do so again (I’ve discussed this in a paper entitled ‘New Gods for Old: Jack Kirby and Classical Mythology from Mercury to The Eternals’). And if Asgard existed in the Marvel Universe, it was only logical that Olympus should exist as well.

The reason the Hercules of the Avengers story had eventually to be retconned was that he was very quickly forgotten in mainstream Marvel continuity. In August 1965, Jack Kirby (with Lee scripting) had introduced a new Marvel Hercules, in Journey into Mystery Annual #1. This was the ‘real’ Hercules, very definitely the demi-god, as he is first met by Thor in Olympus, in a story that is set long before the time of Thor’s monthly adventures; there is even a brief appearance by Zeus. Jack Kirby’s wider engagement with mythology had already been demonstrated by the Tales of Asgard back-up strip that first appeared in Journey into Mystery #97 (October 1963), which adapted Norse mythology into comics form. The encounter with Hercules reads very much like a Tales of Asgard story, except that it does not take place in Asgard, or any other Norse mythological setting. Kirby had worked with Classical mythology in the past (Mercury in the 20th Century has already been mentioned), and would do so again (I’ve discussed this in a paper entitled ‘New Gods for Old: Jack Kirby and Classical Mythology from Mercury to The Eternals’). And if Asgard existed in the Marvel Universe, it was only logical that Olympus should exist as well.

Kirby’s Hercules is notably different from earlier renditions, whilst in some respects being similar. He is bearded, with curly hair in a fillet, and muscular, a bodybuilder type, but he neither wears a lion-skin nor carries a club. Instead of the former he had a short skirt and what is really no more than a sash running from belt to shoulder. In place of the club, he wields a golden mace. Overall, despite the absence of the lion-skin, the appearance is more Grecian than some earlier comics versions of Hercules. This look owed a great deal to Steve Reeves, the American bodybuilder who had become famous for starring in the 1958 Italian movie Hercules. That this was conscious would be reflected in a series of Steve Reeves gags that would turn up in Hercules comics for the rest of the 1960s.

This Marvel Hercules is introduced largely to give Thor another worthy antagonist, but they fight over nothing (who has right of way over a bridge), and the two part as friends. Olympus is presented as a rather more hedonistic place than Asgard; the Greek gods, centaurs, satyrs, etc., seem to spend their existences drinking, dancing, and playing music. It is also worth noting that, with the exception of Hercules himself, the Marvel comics from now on consistently used the Greek rather than the Roman names of the gods, perhaps wishing to distance Marvel’s gods from those DC employed in Wonder Woman, where Roman names were often used, if inconsistently.

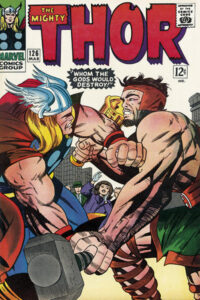

Lee and Kirby brought this Hercules back, in Journey into Mystery #124 (January 1966), for an extended modern-day story, that would run through the early summer, until #130 (July 1966), by which time the title of the book had changed to Thor. Zeus sends Hercules to Earth for a mission. What mission? Well, Zeus never actually tells Hercules, and the strong implication is that he simply wants to get Hercules out from under his feet. Certainly, the mission is soon forgotten. Hercules comes to New York, and meets Jane Foster. He is smitten, which, obviously, doesn’t go down too well with Thor, and the two immortals have another fight. Cleverly, Lee chose the issue in which they fought, #126 (March 1966), to change the title of the book. The cover shows Thor and Hercules fighting, both with hands on Thor’s hammer, almost as if they are struggling for ownership of the comic book. Ultimately, Thor loses, because Odin, annoyed that Thor has revealed to Jane Foster that he and Don Blake are one and the same, saps some of Thor’s power.

Lee and Kirby brought this Hercules back, in Journey into Mystery #124 (January 1966), for an extended modern-day story, that would run through the early summer, until #130 (July 1966), by which time the title of the book had changed to Thor. Zeus sends Hercules to Earth for a mission. What mission? Well, Zeus never actually tells Hercules, and the strong implication is that he simply wants to get Hercules out from under his feet. Certainly, the mission is soon forgotten. Hercules comes to New York, and meets Jane Foster. He is smitten, which, obviously, doesn’t go down too well with Thor, and the two immortals have another fight. Cleverly, Lee chose the issue in which they fought, #126 (March 1966), to change the title of the book. The cover shows Thor and Hercules fighting, both with hands on Thor’s hammer, almost as if they are struggling for ownership of the comic book. Ultimately, Thor loses, because Odin, annoyed that Thor has revealed to Jane Foster that he and Don Blake are one and the same, saps some of Thor’s power.

The first of many Steve Reeves jokes, from Thor #128 (May 1966). Script by Stan Lee, art by Jack Kirby and Vince Colletta.

Hercules is set up as a deliberate contrast with Thor. Where Thor is aware of the responsibilities that a god has, even in a world of unbelievers, Hercules is entirely out for a good time. He likes food, and he likes girls, and the more the merrier. These traits drive the plot. He is spotted by a Hollywood casting agent, who decides that this person will be perfect for a new Hercules movie that is being cast—well, of course he is. Hercules travels to Hollywood, via a fight with the Hulk in Tales to Astonish #79 (May 1966). Unfortunately, it is all an evil plot by Pluto, god of the Underworld. He gets Hercules to sign an Olympian contract that commits him to ruling the Underworld in Pluto’s place. He can only be released from this if someone else fights for him. Of course, that someone is Thor, despite the fact that on their previous two meetings, they had pummelled each other into the dust. Thor does not beat the minions of the Underworld, but cause such a mess that Pluto releases Hercules from the contract, rather than see everything he had built get trashed any further. Hercules returns to Olympus, and Thor heads off for a new adventure (the first of Kirby’s interstellar adventures for Thor, as it happens).

Hercules returned the following year, but not in the pages of Thor. Instead, he turned up in the title that had already seen a version of him, Avengers. In #38 (March 1967), the Enchantress teams up with Ares, and puts Hercules under a spell, and sends him against the Avengers. Her spell is broken by Hawkeye’s sulphur arrow (well, of course), but Zeus is so annoyed that Hercules has gone to Earth that he banishes Herc from Olympus. The Avengers offer Herc a place to stay, and inevitably he joins them from time to time on missions, before being formally inducted into the team in #45 (October 1967). By this time Roy Thomas was writing Avengers, though he had only begun a few issues earlier, and it is possible that Hercules’ induction was Stan Lee’s idea. Hercules provided some important muscle to the team. The Avengers were not as underpowered as they had been in the ‘Kookie Quartet’ days (no-one back then having properly thought through the Scarlet Witch’s ability to rewrite reality at her whim), having added Hank Pym’s Goliath to the roster. But Hercules gave the team the sort of super-strength it had once relied on Thor and Iron Man for.

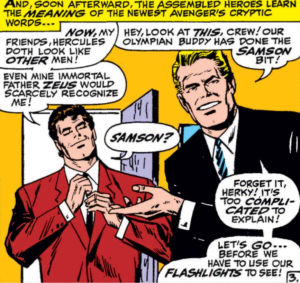

Avengers was drawn by Don Heck, and Heck’s Hercules looked even more like Steve Reeves than Kirby’s had. But Heck also provided some variety for Herc’s looks getting him into modern civvies in #39 (April 1967). Heck’s successor, John Buscema, got to show a Hercules who had shaved off his beard in #46 (November 1967), perhaps intending to move away from the Steve Reeves look. However, it should be noted that Buscema’s Hercules also looked rather more like the Hercules who had appeared in Superman stories in the later 1950s and early 1960s.

Script by Roy Thomas, art by John Buscema and Vince Colletta. The ‘Samson’ joke is obvious, but may also be riffing on the fact that many Italian ‘Samson’ movies were marketed as Hercules movies in the US. Also, the Hercules of Superman stories was often teamed up with Samson.

Almost as soon as Hercules officially joined the Avengers, he left again, in #50 (March 1968), where he returned to Olympus, though not without regret for leaving behind his mortal teammates. He would return to the Avengers, but not until 1972.

Hercules’ history in 1960s Marvel comics is something of a microcosm of the character’s history overall. It is never quite clear how he fits into the wider Marvel Universe. He was originally a slightly different person for Thor to trade blows with. In Avengers, he generally functions as a substitute Thor (notably, almost as soon as Hercules leaves in #50, Thor comes back). His periods in the team never seem to last long, as writers generally prefer Thor. Hercules had a longer period in the Champions, but never sat comfortably in that team (but then no-one really sat comfortably in the Champions). Nor did his occasional liaisons with She-Hulk ever amount to much.

Others are better qualified to write about more recent versions of Hercules, and have done so. But his minor role in the Marvel Universe may, at least in part, perhaps be because Norse heroes fit more closely with the values that modern society considers heroic. For the Greek heroes, heroism was linked to the performance of great deeds, which would gain glory; but Greek heroes are much less self-sacrificing, and one can be a hero without actually doing good deeds. That is reflected in the way in which Marvel’s Hercules often is more concerned with having a good time than fighting the good fight, and when he was staying with the Avengers, he sometimes had to be cajoled into getting involved in their missions. Similarly, the Greek gods, with their ambiguous morality, never quite sit as comfortably in the Marvel Universe as the Norse gods. Olympus is a place that is there, but not often visited.

In general, Hercules had a strong place within 1960s US popular culture. Plenty of comics starring Hercules have come out from various publishers. Dell published comic book adaptations of the 1958 Hercules movie and its 1959 sequel, Hercules Unchained. In 1963, Gold Key released two issues of The Mighty Hercules, based on an animated cartoon series. Charlton produced Hercules: Adventures of the Man-God between 1967 and 1969, and DC published Hercules Unbound between 1975 and 1977, in which Hercules was seen in a post-apocalyptic 1986. But it took until 1982 for Marvel to give its Hercules his own comic, and even then, he was only allowed mini-series until 2008, when he finally took over Incredible Hulk. Even then, his ongoing title only lasted a couple of years before being brought to a close. Nor has Hercules put in an appearance in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, though he might be seen in the upcoming Thor: Love and Thunder. Overall, Marvel’s Hercules has never quite fulfilled the potential the character has.

A version of this article was first presented at the Drawing on the Past conference in London in September 2018, and then again at the University of Notre Dame’s London Global Gateway Faculty Seminar. My thanks to the organizers and audiences of both events.

Tags: Avengers, Hercules, Marvel, Marvel Comics, Superheroes, Thor

I haven’t yet seen Thor: Love and Thunder, but I gather Hercules is indeed in it.

Good write up, man! I agree with most of this. The only part that I’d disagree with is that his tenures with the Avengers have always been brief or as a replacement for Thor (They’ve served together more than once). A while ago, someone actually counted up the Avengers members by the length of time that they were on the active roster and Hercules was in the Top 10. After Captain America, Thor, Iron Man, Hank Pym, Wasp, Scarlet Witch, Hawkeye and Vision, but above Quicksilver, Black Panther and Black Widow.

Thanks. He does always feel peripheral to the Avengers – of the runs I reviewed for Slings and Arrows, it’s only really in the Thomas era that he plays a significant role. I gather he’s there quite a bit in the 1980s, but I’m not really familiar with that period of the Avengers.

Hercules is not a superhero. Neither is the Shadow or the Spider. Perhaps you have noticed superheroes wear costumes. You can’t be the thing that you influenced.