The ’Nuff Said! Interview: Russ Heath

by Ken Gale 31-Jan-21

At 2001’s Big Apple Convention in New York City, Ken Gale, with Alan Rosenberg and Jeffrey Lindenblatt, interviewed legendary comic book illustrator Russ Heath.

[For nine years Ken Gale, in conjunction with Ed Menje and Mercy Van Vlack, hosted and produced about 400 episodes of ‘Nuff Said!, a comic-book themed series for New York’s WBAI radio station, broadcast from the Empire State Building and live-streamed over the Internet for the last several years of its run. Ken’s show covered all styles and all eras of comics, pointing out the diversity and richness of the art form to an audience who were often unaware of the versatility of sequential art.

[For nine years Ken Gale, in conjunction with Ed Menje and Mercy Van Vlack, hosted and produced about 400 episodes of ‘Nuff Said!, a comic-book themed series for New York’s WBAI radio station, broadcast from the Empire State Building and live-streamed over the Internet for the last several years of its run. Ken’s show covered all styles and all eras of comics, pointing out the diversity and richness of the art form to an audience who were often unaware of the versatility of sequential art.

’Nuff Said! was regularly scheduled from 1993 to 2002, but Ken has done a number of specials and guest spots on other WBAI broadcasts, continuing to show how well our art form fits in with many different, seemingly disparate topics.

The ’Nuff Said! archive, used with Ken’s full permission and cooperation, is a “snapshot album” of the careers, influences, and often surprising opinions of a wide range of comics creators, several of whom, sadly, are no longer with us, and many of whom are seldom if ever interviewed by comics journalists.

At 2001’s Big Apple Convention in New York City, Ken Gale, with Alan Rosenberg and Jeffrey Lindenblatt, interviewed legendary comic book illustrator Russ Heath.]

‘Nuff Said!: When did you first start drawing professionally?

Russ Heath: The first professional jobs were for Holyoke Publishing. They were stories I did in High School, in the summertime. My father knew somebody at Holyoke, and made an appointment for me and dragged me in there, like—“You should go to work!”

NS: What year was this?

Russ: 1942. And they gave me a strip called Hammerhead Harley—first I had to practice a couple of weeks, because I thought it was all done with pen and ink, or brush and ink. It was for Captain Aero Comics, about this guy who had a miniature submarine, and every issue he’d sink half the Japanese Navy! So I did two of those and then the war came and interrupted, so after I got out of the services, I started in advertising; I looked for work for, seventy days I think it was, before I got my first work, which was sharpening pencils for art directors. I took my portfolio and I went around—nobody wanted to see anybody before ten o’clock, nobody wants to see anybody after four—before I got my first job. I think it was for $3, and I spent $15 on laundry and travel expenses, so I started looking for extra work at lunchtime. Two out of three people you go to see at lunchtime are out having lunch, so finally I walked in on Stan Lee and he says, “I’ll give you three times that!” and I’m you know “Wow”, so I started working at Timely, which they called it in those days, and after a while he said, “You know, you don’t have to come in, you can do them at home if you want.”

NS: Were you doing full pencils right away?

Russ: I’m not certain—I know it was Two-Gun Kid, the character, that I started in the office on, of course to be followed by Kid Colt and the Arizona Kid, they were all called “Kid” something. It’s hard for me to remember, I’m not sure about that pencilling and inking division thing. I was appalled at the pencilling stage, having to sit there and put all that shading in. I said, “You could take a brush and just put that in instead of sitting there for hours!” I asked why they didn’t just shoot Photostats—they didn’t have Xeroxes in those days—use those and then we wouldn’t have to ink it, shoot right from the pencils! So they did, and they said, “Wow. This is terrific. Everybody’s going to do pencils from now on, no more inking!” So they fired forty inkers. Which made me very popular for a couple of years, with all the inkers! So then they found out that it didn’t work, that I was the only one who was fast enough to do all the detail in the pencil that they could shoot from.

NS: Which artists influenced you when you were in High School?

Russ: When I was real little, the only access I had—I think I had like the eleventh issue of Famous Funnies, which was the first comic book, when I was seven years old. It was the first time I’d ever seen one. And of course in those days they were all reprints of the Sunday Funnies, then later on they used fresh material, so the only real place you’d get to see stuff was in the newspaper strips, which in those days were huge big panels. My father, despite the Depression, he was able to bring two papers home, so I’d get down on the floor and pore over these things,

I guess some of the first ones were Dickie Dare, which Caniff did before Terry and the Pirates, and of course I followed Hal Foster doing Tarzan.

NS: Did you use to copy them?

Russ: When I was a little kid, yeah, but—even then, I tried to stay away from copying, because someone told me you’re not supposed to copy! Then, of course, I felt that Foster really hit his stride when he did Prince Valiant, that was amazing stuff. I also liked Alex Raymond, except that I thought there wasn’t enough vim and vigour, his people looked rather static in their facial expressions, he didn’t really go into exaggerated expressions, they were more like still photos which he worked from. I loved his Rip Kirby stuff, he did some very cool stuff on Kirby or Secret Agent X-9, and then there was Captain Easy, which was a very simple art style. So those were the first influences. Scorchy Smith…

NS: Who would you say you more close to in style?

Russ: I think that would be for someone else to say rather than me, but—I can’t say Foster, because looking at his originals, they don’t look like mine!

NS: I personally would think Foster. You’re closer to Foster. I can’t pay a bigger compliment than that.

Russ: Thank you very much.

NS: You’re known as one of the premier war artists. When did you start working within that genre?

Russ: Well, there’s a reason why I got into—I was doing Westerns a lot, and then Horror stuff, and I even did a few Romance comics—very few, but… in war and western, and in Sea Devils, there’s no straight lines! Everything underwater fades away, or its rough sand, or rough rock… same thing in a war comic, it’s dirt and rubble… you can’t draw a tree “wrong” because that’s where the limb was! But if you’re going to do Batman, you’re going to have buildings, and seventy-five windows, and panes of glass that all have to be ruled, and that’s a nightmare for me! So I stayed away from them; nothing to do with cities, please! In westerns, they all hewed that stuff out with axes, so the more uneven it was, the better it looked! Plus it’s great for action.

NS: Yeah, but planes, boats, they have fine lines, straight lines…

Russ: Yes, and I used to build them, to get them right, because most of the photos of planes until around World War II, they were of parked airplanes, they’d take them from a lot of angles, but you can’t get foreshortening, shots looking up at the bottom of the plane… So I’d buy the model and build it, then you could, for example, bring the tail real close. I had a way of holding it in front of the paper, you know, here, then you’d line it up and draw around it, and then you’ve gotta move over, you’ve got to keep moving ahead to where you’re working. But it’s the only way I knew how to do it!—What was the question again?

NS: When did you start doing the war stories?—though I like your answer a whole lot better than my question! Some of my favourite work of yours is the stuff you did with Gil Kane… You did some wonderful stuff with him…

Russ: Yeah, Wells Fargo, for Western Publishing. We did several, two or three different characters from movies or TV that we did, and then when we were due to do the second Wells Fargo book, he got too busy, and you could see the art change in the centre of the book when I took it over.

NS: Who were some of the publishers you worked for, as you progressed through the Fifties? Because you worked for a lot of publishers…

Russ: I never worked for Charlton; I did work for a short while for Gleason, I did some romance comics… There was one outfit I did some stuff for, it was called Fox, and I heard that they were going bankrupt, and I thought, “What can I do to get them to pay me, if there’s only a certain amount of cash to distribute among the people they owe, and why should they pay this guy rather than this one?” So I sent a bill to them offering 15% discount for cash in ten days, and, well, that’s a saving, so I got paid and a bunch of guys didn’t!

NS: So you were one of the few people ever to get paid by Victor Fox? Russ Heath and Joe Simon.

Russ: Of course, there was a big layoff around 1950; normally there’d be kind of a seasonal slump, but this was a big crash, and everybody moved around. I was going to all the places; I went over to St. John, where Joe Kubert was doing Mighty Mouse, 3-D comics, and then Tor, the caveman type thing. So I walked in and Norman Maurer interviewed me, he was familiar with my work, and Kubert walks in and says, “You don’t have to look at his portfolio, he’s in!” So I worked on the Tor book, doing backgrounds and single-pagers, and I was still interviewing around, and somewhere in that time period I went down to DC, and Kanigher hired me to do a war story, which I remember involved a lot of frozen ice, and that was the start, and I worked pretty steadily for DC over the years. But I’d go here and there, sometimes go over to work for Stan Lee, and here I am working for Stan Lee now, over half a century later, for the same man who gave me my first steady job!

NS: What are you doing for Stan right now?

Russ: Stuff for the Internet; they’re doing little four-minute bits of these characters and shows, in the hope that they’ll license and buy, that they’ll do ’em in Japan and make toys, and do movies, animated shows.

NS: Are you designing some of the characters?

Russ: Some, yeah.

NS: Are you getting a cut if they do licensing?

Russ: No, they give me a good enough salary. The first fifty guys who worked for him—and I was one of the first ten, I guess—they got Stock Options, and I’m about to cash those in!

NS: ‘Cause it’s an Internet company, right? Are we able to see any of this on the Stan Lee website?

Russ: Yes. Some of my cover recreations, I think the ones you saw are probably all on there. I’m doing one called the Accuser. In the beginning, they looked like my stuff, but then—I figured the best thing to do is to try and make yourself indispensable, then you’re in a better position if you ever want a raise or anything, so in the first six months, I did that, and everybody said, “Oh Russ, you’re it!” Then, I guess, jealousies and little things always set in, and they think, “Oh my God, suppose he gets sick or dies?” so they started divvying up my work. One guy would do the storyboard, another guy would do the colouring, and—I had a few fights with the colourist, he wanted total control of the lighting and the colouring, and part of what Stan likes about my work is the lighting—so they got it all down so I could be replaced like that, you know! Now it’s kind of swinging back, they want to have someone do the origin story of the Accuser. Just in black and white with shadowing, like a comic book, and they’d run that.

NS: Are you doing anything different now that it’s on the Internet, as opposed to the printed page?

Russ: Yeah, it’s like half-animation—it’s not full animation but there is movement in it, so you’ve gotta lead in from one point to another. Every picture in a comic book can be a cut and another angle, but here it’s all got to be connected—“This guy’s going to hit this other guy, so we have to show him before he hits him, while, and the result.” It’s got to flow, as in regular animation, except that they’re doing less of it, because the movement part is more expensive.

NS: Do you have to leave the speed lines out?

Russ: Yeah, You can’t use speed lines.

NS: So you’re learning new skills, after all these years?

Russ: Well, I’d say more I’m putting up with them… The world doesn’t want my way of doing things anymore! But that’s natural.

NS: Going back chronologically, we’re now at the 1950s, and that’s when a lot of your work started appearing at DC, which turned into your major company from then until recent times.

Russ: I was just doing individual series for a while—if you go back to certain years, it’s not Sgt. Rock and it’s not Haunted Tank, most of that stuff I’d rather nobody see anyway, because I made some major improvements in my work. There was this lady who moved in with me, who had been to three of the best art schools in the country—they finally told her, “There’s no sense in you going to school any more, you know all we can teach you!” She taught me things like the theory of negative space, stuff like that—I had sold a lot of my stuff, so I had the professional approach, so we’d set up two art boards, she’d work and I’d work, and I’d tell her what to change to make it professionally acceptable, and she’d tell me about, like, the negative space thing and that was tremendously helpful. I used to do figures like: “Here’s the panel, here’s two guys talking face-to-face in a perfect letter M with the space around it,” and that’s the worst thing you could do. She helped me understand that the space, when you colour all the figures in a panel, if you colour the space blank, you lose the pleasing arrangement of the space. So I made a big boost in the quality of my work. I used to have no idea why some of my pictures were good and some were bad, until I learned that, and of course there was much more to it than just negative space…

NS: So you got the benefit of several years of art school by having this person living with you?

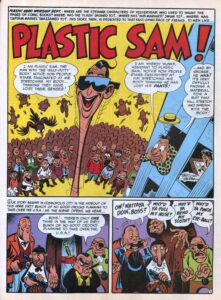

Russ: I wouldn’t say that, but I did learn a couple of theories, which was a big help to me. That took place during the Sea Devils run, 1962 I guess. Harvey Kurtzman, all along I’d been working—I’d call him up to go to lunch, and he’d give me a job to do. I never put the two together, I never realized that if I had called him up for lunch more often, I might have become one of the insiders of that group of DC artists. I met during the Hey, Look day, when he was doing that feature for Stan, and then he started Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat, and I did a story called “Observation Post”, in Frontline Combat, and then somewhere along in there came Mad Magazine, and I did a take-off on Plastic Man called Plastic Sam, did other little things… I did a back cover for Mad, I think it was called “The Spring Issue”, it had a big bedspring on it, there was a take-off on the Petty Girl, called the Heath-y Girl, ‘cause we needed that y sound on it to make the slash, so that the signature would look similar. That piece was just auctioned off, I understand, by Russ Cochran, and I thought, “You know, they ought to send me a token payment.” Somebody’s making all this money by selling the originals.

So, anyway, everything that Harvey ever did, there was Humbug, there was Trump magazine done for Hefner, which was—well, here’s the break-even line, and the first one was down here, and the second was higher, and the third one would presumably have been above, and have more than broken even, but the bankers don’t work that way; they said “Done”, and cut off the funding. When they started Humbug, all the guys threw in a couple of grand, or whatever, and that didn’t go because it was an odd size, and none of the retailers knew where to put it! Then I think Warren Magazines backed Harvey for Help!, which—there was a lot of art, but it was mostly photos, like the fumetti like the Italians have, when they put in word balloons over photographs. I posed for some of those, actually.

NS: Did you pose for any of the ones John Cleese was in? John Cleese was in a lot of the fumettis in Help!…

Russ: No, let me see… There was Jim Hampton, I don’t know if anybody knows who he is, but he was in that movie with Jane Fonda about the meltdown…

NS: China Syndrome?

Russ: Yeah, he was the head of the nuclear plant, he was in one I did, and there was this one where an actor, I guess he’s more of a stage actor though I’ve seen him in a few commercials, and I was supposed to trip him as he comes forward with this tray of drinks, we did it about four times, each time as he moved across, I stuck my foot out like I was tripping him, and on the fifth time—he couldn’t see my foot, because the tray was blocking his vision—he actually tripped and fell! Tore his pants, got bloody knees, a bloody elbow, they had to fix him up. They ran a shot in the beginning of that issue: “This is a man flying to a bloody end for real!”

NS: Did you work with Gilbert Shelton, or Kim Deitch, or Art Spiegelman?

Russ: Somewhere along the line I met Art Spiegelman; in 1976 I went to Italy, I think there five people representing the United States, at the Luca Convention, a huge convention, they had a big old opera house, and where the boxes had been, they had people windowed in there who were translators. There was Art Spiegelman and a lady—his girlfriend, wife, I don’t know what—there was Joe Orlando, whom I didn’t really know except to say hello to at that point, but he could understand Italian, and speak it well enough to be understood, so I tried not to let him get more than twelve feet away from me, because I was afraid I’d be marooned! We became friends—there was one funny story, we had rooms next to each other in this villa, and he wants to rinse out his shorts and hang them up to dry for the next morning, so he sees this line hanging there, and he pins them up on this line, and a few minutes later there’s this bang bang bang on the door, and all these chambermaids barge in, and Joe’s just got his skivvies on, he’s trying to hide, and they all rush into the bathroom and come out laughing! Turns out that was the emergency cord that you pull if you need help! So we were good friends and started sending Christmas cards and stuff… in fact when I’d heard that he died, two days later I got a Christmas card from him, which kind of shook me up. I mean, you expect things to be in an orderly sequence…

NS: Is it true that there’s a quarter of a million people go to Luca?

Russ: Well, it’s not as big as it used to be. Because I went again, I was anxious to go, in 1986; there was Al Williamson, Jeff Jones, Kirby and his wife Roz, and Jeff was pretty young in those days, and he got so drunk he was falling down, and he went outside so he wouldn’t get sick on anybody, he was falling over in the yard! So, Joe was in the second group I went with, in ’86…It’s really something over there; they don’t have (social) classes, in the sense that a waiter is this class and you’re another class, it’s like everybody, that’s what they do, and they’re just as good as you are. So you make friends with the waiter; the waiter saw the portfolios in one place we ate, realized we were artists, and he asked if we were coming again on a particular date. Which we were, so that second time he brought out his daughter in her Sunday best, Confirmation dress, whatever, and we gathered we were expected to draw pictures of her! From then on, we could do no wrong; they were closing in the afternoon at 2 o’clock, “No, no, come in, we’ll take care of you; no, you don’t want to order that, let me order for you.”

NS: I find it interesting that during your career, you’re more famous for doing war and western comic books. When you started, they were just beginning, they built in popularity and reached a peak, until now, when they’re almost gone.

Russ: Well, where’s the western movies? What was the last good one, there was Unforgiven… I’m sure Clint Walker couldn’t get work these days!

NS: You had the distinction of being the last artist to work on a western comic strip, with the Lone Ranger, which will probably never happen again—

Russ: I didn’t want to take that on; the guy with the mask—where does he live? What hotel will take him with a mask on? And I wasn’t sure that Tonto wasn’t fooling around with Silver—but anyway…

((laughter))

Well, I think I did westerns for Timely, they weren’t doing westerns at that time at DC, I’d done a lot of covers and stories for Stan, and I was just turning it out, I didn’t really notice it building up.

NS: The end of that genre, and the war genre, was caused because of the Direct Market, and the loss of the general readership.

Did you do any of the Nam comics for Marvel?

Russ: I did a story called Hearts and Minds, about Vietnam, and—of course, the research that I had on hand was all for World War II, nothing about that era. For one thing, World War II was such a short span of years that they barely changed anything, uniforms, weapons, everything stayed the same; so once you had that, you had it all. Vietnam went on for so many years that they kept changing everything, the weaponry, right down the line, it was like eight years. I didn’t do any work for a month, I was out buying big books on Vietnam, researching, putting it all together—you can spend an awful lot of time messing with that stuff. I finally got it done, and I expected they would do a huge print run, and I would get some residuals. The residuals kicked in around 3,500, and then the Gulf War occurred. So they went “Oh, nobody wants to hear about Vietnam any more, now the Gulf War’s happening”, so they cut the print run down, and my residuals cheque was twelve dollars! I called the writer and asked, “Did you get your twelve dollars?”, he said, “They won’t even answer my phone calls!”

And it’s so silly, I think a story could be about a housefly, and if it was really good—I still think you could do a good western story now, and I believe it would be bought, just because of its quality.

NS: Yeah, but not everybody does it really good, so you have to go by the average, especially since DC brought the western genre back, but they’re doing it as kind of fantasy-oriented… sort of the X-Files in the nineteenth century, nobody wants to do a straight western anymore! They don’t trust themselves.

Russ: The Europeans do “tragicomedies” or other combinations where they mix this genre with that, wonderful stuff, I was a fan in the 1950s, I used to go to the foreign film theatres, every time I snuck away from my wife, delivering scripts—it took me all day to drop off a script and deliver a new one!

((laughter))

That was my day off! And I often wondered why the Americans didn’t do horror westerns. Because then you’re attracting two audiences, the ones who love westerns and the ones who love horror…

NS: It’s more like you’re alienating two audiences. But DC did try that with the Haunted Tank…

Russ: That particular series… I was bored to tears because it was the same story every issue! Jeb Stuart’s got a situation, and he talks it over with the ghost general, and they think he’s going nuts, he takes some action based loosely on the General’s suggestion and it works. And then there were four of them in the tank, and it waters it down the more characters you have, because you’re dividing your attention and your energies.

Some of the Sgt. Rocks, they focused either on Rock himself or one of the guys in Easy Company, spotlighting the one person so that you could get their reactions, their characterization, which I liked a lot better.

The worst was the Sea Devils, because you have to put four of them in every panel and where’s the protagonist? It was really a pain in the butt… sometimes I’d just draw a fin sticking into the corner of panel to represent the fourth one!

NS: So the Legion of Super-Heroes is not for you!

((laughter))

Russ: No!

NS: What was that thing you were saying earlier about the New York Times?

Russ: The Lone Ranger was syndicated by the New York Times, even though the Times doesn’t carry comic strips itself. They wouldn’t allow the originals to be kept. Gil Kane turned it down, so I took it on, much as I thought the Lone Ranger was past his time, I thought who knows? I’m not the final word, maybe it’ll be a good paying job. I always took full-size Xeroxes of my work, so that in an emergency, if the art got lost in the mail, they could shoot from those. So one time they called me saying “Where’s the package?” and I’m, “You didn’t get it? You’ll have to shoot from the Xeroxes!” and I had the original hanging on my wall…

((laughter))

But you couldn’t pull that all the time! Then they did something that made me really angry and upset, around four years later, they called me up and said, “Do you have the originals? We can’t find them!” They couldn’t give them back to the artist, but they can lose them!

NS: That was around the time they were looking at a Lone Ranger movie, there was all that controversy about Clayton Moore wasn’t allowed to wear the mask for public appearances any more.

Russ: The movie didn’t go, it was bad, they had to dub the lead guy’s voice, but they tried to stop all other versions.

[Will Morgan: The movie in question is 1981’s Legend of the Lone Ranger, starring previously (and subsequently) unknown Klinton Spilsbury, who was eventually dubbed over by James Keach. Negative publicity, particularly about the lawsuit preventing Clayton Moore, the much-loved actor who played the Lone Ranger on TV for most of the 1950s, from making personal appearances in costume, deterred audiences, and the film lost $10 million.]

NS: I’d like to ask for a few quick impressions of your other works. You’ve mentioned Haunted Tank, but could you tell us, for example, what it was like to work on Sgt. Rock, because that’s probably your longest continuous strip that you’ve worked on.

Russ: Probably. Joe Kubert was doing so much that he wanted someone to take some of it over, so he chose me. The first job I did, I wanted to switch over so as not to jar people, so I tried to do it as “Kubertish” as I could, and then of course my own style quickly took over by the end of the second or third issue. I did Rock for a long time, but I was always doing other stuff—I worked for National Lampoon in the 1970s, in ’62 I started working on Little Annie Fanny for Playboy… eventually I went to quit that, because I wanted a raise, and Harvey Kurtzman was “But it’s working for Playboy! What more could you want?” and I said “I need the money for my family.” So I finally got disgusted and quit, and Harvey just spiralled into the ceiling! But by the end of the day Hefner was on the phone, wanting me back!

I was getting paranoid by this time in New York—I figured I couldn’t carry enough ammo to go on the subway, it was getting pretty bad. I was pretty late with my work, because I was trying to make it so good it would compensate for my being so damn late! So there were big steps forward in the quality of my work, but eventually Joe just said, “We won’t use him anymore.” I never knew, I only heard that in the last few years.

One other thing about Joe Kubert, he and I were on a panel a few years back, and Joe always takes things pretty seriously. So for half an hour, twenty minutes, he’s telling about the research that we did to get everything right, and then I say, “Well, you know that story that Mort Drucker did, that was all supposed to be off-panel talk coming from the nose wheel of this B-17 bomber? All the pictures took place with this thing just hanging there? The only trouble was, the B-17 didn’t have a nose wheel!” and Joe turns to me; “You just ruined my last twenty minutes!” We broke up laughing…

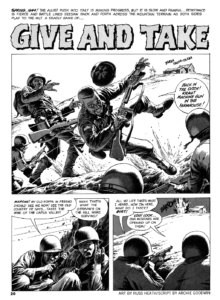

NS: One of the most famous stories you ever did was for Blazing Combat, for Warren—the only war story you ever did for them.

Russ: Well I was working for Jim Warren on his other books, but that war story, here I was going to be with all my peers, Wally Wood, John Severin, you name it—so I thought: “This has got to be the best work I’ve ever done, to be sure that I can deserve to up there with them.” So I tried to make a collector’s item out of it. I took one of the Playboy photographers, I dressed as the character, had my own helmet, the fatigues and the belt, all the paraphernalia, and we shot about forty photographs for reference. I took about a month and a half to do that story, and it’s a good thing I did, because everybody else in that issue turned in nearly their best ever work! That story became really famous. One time I broke my wrist, and I asked a friend of mine, “Do you know anybody who could help, a young student maybe, because I can’t pay very much, but maybe I could give them lessons on the side.” And he suggested a young lady, gave me her number, and I was thinking she wouldn’t know who the hell I am, but when I phoned and told her my name, she recognized me! She was carrying that story on her person at all times—she had it in her bag!

[Will Morgan: The story in question is ‘Give and Take’, from the final issue, #4, of Warren’s Blazing Combat.]

NS: Do you have any anecdotes about Jim Warren? I know he’s one of your favourite people…

Russ: Well, Jim and I had a falling out, it was a mistaken thing, and I don’t think we spoke for a year, I told Harvey “I’m not so stubborn that I won’t take his money, but I will not go to his office”, then I met him in a bar one evening, and we started chatting, and I felt I couldn’t hold a grudge, so the hell with it, then I got robbed at one of Phil Sueling’s conventions, they burgled my room and I was broke, and Warren handed me $200, which was a lot more back then, and I assume I could pay him back in a few weeks. But things didn’t get better, the business was kind of down, and I was struggling to pay the bills with the children and all, so, I think it was two years later, I walked into his office and said, “I owe you $200”, and he pulls open his desk drawer and shows me the paperwork for Small Claims Court, all filled out!

NS: How about Robert Kanigher?

Russ: How about Robert Kanigher? They do say, “If you can’t say anything nice…” Kanigher was a very odd person, that’s for sure. One time, he was talking to one of the artists, and he said “You’re not getting the feeling! You’re not getting the feeling of hat it’s like to be fighting and rolling around the campfire with the Indians!” and he had the guy get down on the ground and roll around on the office floor! And I thought, “Okay, I’m going to start wearing a suit and tie when I come to the office.”, because this guy was just in casual clothes, and Gil Kane, everyone else, started following suit—literally!

[After this interview was originally conducted, Heath continued freelancing for various publishers until the 2010s, with his last multi-page story appearing in Marvel’s Immortal Iron Fist #20 in 2009, and his final single page in issue #11 of Dave Sim’s Glamourpuss in 2011. In 2014, however, he wrote and drew one more comics page, “Bottle of Wine”, commenting on how one of his war comics panels had been ripped off by the plagiaristic “Pop Artist” Roy Lichtenstein.

Russ Heath was inducted into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame in 2009, and passed away August 23rd, 2018, at the age of 91.]

Tags: Blazing Combat, Captain Aero Comics, Harvey Kurtzman, Haunted Tank, Hearts and Minds, Help!, Jim Warren, Joe Kubert, Joe orlando, Lone Ranger, Norm Maurer, Playboy, Robert Kanigher, Russ Heath, Sea Devils, Sgt Rock, Stan Lee, Two Gun Kid