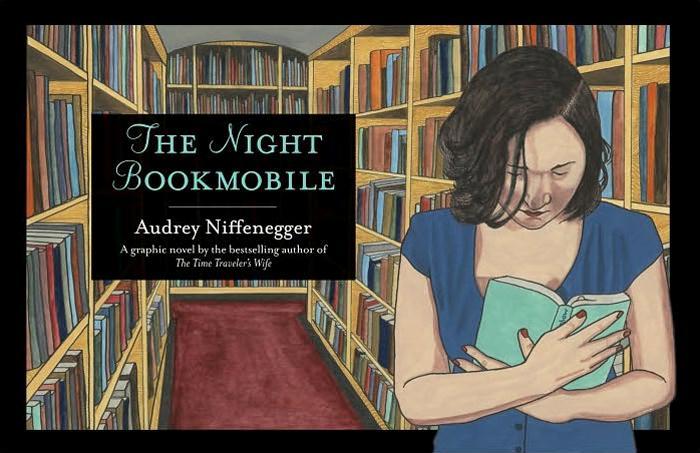

The Night Bookmobile

Reviewed by Jonathan Bogart 11-Feb-11

This will undoubtedly be one of the best-selling graphic novels of the year; and if more than a handful of geekologists, whether mainstream or indie, take note of it, I’ll be surprised.

This will undoubtedly be one of the best-selling graphic novels of the year; and if more than a handful of geekologists, whether mainstream or indie, take note of it, I’ll be surprised.

Audrey Niffenegger, for those who don’t keep up on the New York Times Best Seller list, is best known as a novelist; she wrote The Time Traveler’s Wife (haven’t heard of it? Ask your mom) and Her Fearful Symmetry. She’s a solid middlebrow writer who takes themes of unexpected resonance and depth and applies them to fairly conventional interpersonal narratives, magical realism for corporate suburbia.

This is her third “book in pictures.” The previous two, The Three Incestuous Sisters and The Adventuress, were abstract and metaphorical — art books, in fact, with heavy bindings and price points to match — with beautiful, stylized art that embraced both cartoon simplification and medieval illuminations. The Night Bookmobile, while colored in the same gorgeous watercolor style, is oddly less accomplished.

The Three Incestuous Sisters and The Adventuress were more or less picture books for adults, told in single images with separate text; The Night Bookmobile is a full-blown graphic novel, with panel transitions, word balloons, and captioned narration. It’s also highly photoreferenced, with painstakingly rendered perspective and awkwardly-posed characters with mannequin expressions. Niffenegger is a fine cartoonist, easily able to depict the muted emotions of stylized figures, but her attempts at life drawing are undercut by the stiffness of her line and the overreliance on photo reference.

Photographs capture a moment in time; but people are almost always in transition, their bodies moving from one place to another, their faces shifting from one expression to another. We know how to read photographs, because we can fill in the moments immediately before and after; the realism they capture is interpretable as a frozen slice of “reality.” Drawings made from photographs, however, unless they’re channeled through a specific sensibility, an individual stylizing voice which overrides the artificiality of the pose, always look unreal, closer to the uncanny valley than to either cartoon iconography or photographic naturalism. Niffenegger is a skilled artist, but she lacks the training that would allow her to instinctively know when to push the image forward into caricature, to find the extremes of motion and emotion (extremes, that is, within a spectrum which every cartoonist defines for themselves, Adrian Tomine as much as Basil Wolverton) that good cartooning is all about.

This will probably not matter to the book’s target audience: The Night Bookmobile is a celebration of reading. It’s a celebration which doesn’t flinch from depicting the sacrifices that a life spent obsessed with books demands, but in its depiction of a vast library as paradisiacal (Borges is never mentioned, but is an obvious reference) and of books as the central relationship in the protagonist’s life, it fits tidily into a Book Club vision of the world, in which people who are unimpressed with books are consigned to the outer darkness and the highest vocation imaginable is Librarian.

I should perhaps mention here that while I’m as obsessed with books as anyone in my age, education, and weight class (and have the emotional stuntedness and social dysfunction to prove it), I’m unpursuaded by the Up-With-Books rhetoric that libraries, teachers, publishers, and people who think of themselves as Book Readers like to employ. The repeated narratives, frequently heard in certain circles, that reading for pleasure is imperiled, that literary engagement has fallen off from some mythical high point located in the nonspecific past, that it doesn’t matter what kids read so long as they read, always find me unsympathetic and looking for plot holes. Of course it doesn’t matter what kids read; but it also doesn’t matter — the survival skill of basic literacy aside — that they read anything. Humanity transmits itself across whatever platform it is given, and reading, in the abstract, makes no one more moral than they would otherwise be.

But Niffenegger doesn’t show her character’s dedication to reading as an uncritical positive, or at least the story is interpretable that way. Without giving anything away (there’s at least one startling twist), it’s possible to see her main character as stunted and unable to live life because she’s so obsessed with her own past as chronicled in the pages of books. The Night Bookmobile of the title is a Winnebago that holds all the books she has ever read — magazines, newspapers, and backs of cereal boxes included — and if she hasn’t finished them, the pages after the bookmark are blank. (Only printed material seems to count, as in the rhetoric of the Book Readers above; although the story takes place in an unspecified present, there’s no terminal in the Winnebago where she can revisit the webpages she’s viewed.) She’s fascinated by it, and after being politely shown out at dawn, dedicates her life to finding the Bookmobile again.

As a bibliophile and sometime librarian (I love libraries; it’s library culture I’m wary of), I can’t help but respond to the constant images of bookshelves stretching off to vanishing points; but the narrowness of the ideal, the essential narcissism of the premise, horrifies me. Books offer endless promise; as long as there are new books to read, life remains. If her ideal is to obsessively retrace only the ground she has already covered, to squat in the domain she has built and never venture out again, then she is already dead.

Tags: Abrams, Audrey Niffenegger