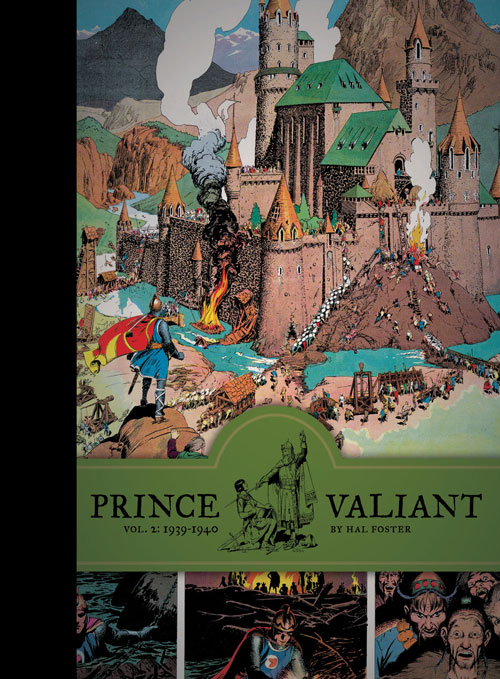

Prince Valiant 1 & 2

Reviewed by Jonathan Bogart 06-Nov-10

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, Hal Foster must be the most highly-flattered American cartoonist of the twentieth century. A generation of newspaper strip cartoonists, two generations of magazine and children’s-book illustrators, and (what are we up to now?) five generations of comic-book artists owe not only their style but an entire method of processing black-and-white images — high contrast, richly detailed, figure-oriented — to Foster.

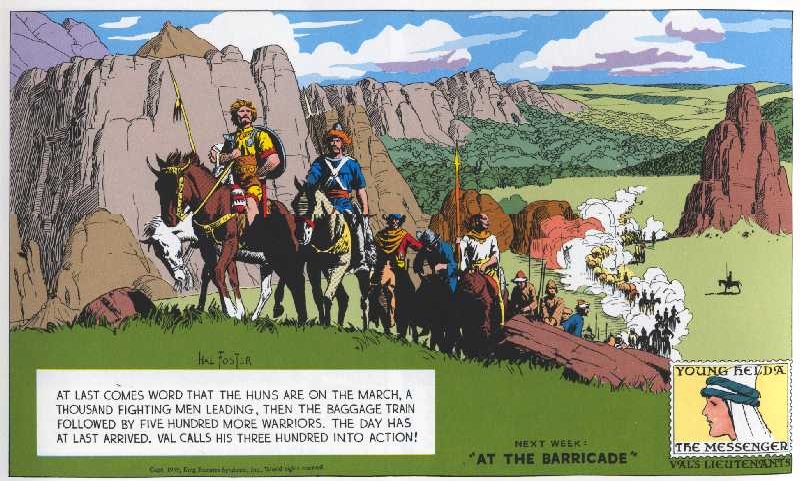

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, Hal Foster must be the most highly-flattered American cartoonist of the twentieth century. A generation of newspaper strip cartoonists, two generations of magazine and children’s-book illustrators, and (what are we up to now?) five generations of comic-book artists owe not only their style but an entire method of processing black-and-white images — high contrast, richly detailed, figure-oriented — to Foster. Which makes the perennial discontented-nerd argument about whether his work really “counts” as comics, because it doesn’t have speech balloons and sound effects, even more unnecessary than such arguments usually are. Of course it’s comics — but a specific, almost sui generis form of comics that demands that the reader exercise somewhat different muscles than all other comics require. Prince Valiant is best read with a sort of suspended urgency, neither the headlong rush of more explicitly cartoony comics nor the patient sentence-by-sentence derivation of prose, but a middle way between the two. It is not, by our current lights, a perfect fusion of image and text — when Sir Gawain falls into a washbucket, bringing a clothesline down with him, we don’t need to be told that that’s what’s happening in a caption just below the picture — but the slowing-down that such a caption requires forces us to linger over the image, to participate in the ongoing reconstruction of the scene before us rather than passively watching it unfold, as we would a movie or a play. It’s a technique that recalls the swashbuckling movies which were no doubt Foster’s most immediate form of inspiration: the dozen films Errol Flynn made with Michael Curtiz, in which action was underlined through dialogue, because otherwise the ten-year-old boys who were the movies’ primary audience might not be able to keep up. When Foster works his plot into its highest pitch, one can almost hear the Erich Wolfgang Korngold soundtrack.

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, Hal Foster must be the most highly-flattered American cartoonist of the twentieth century. A generation of newspaper strip cartoonists, two generations of magazine and children’s-book illustrators, and (what are we up to now?) five generations of comic-book artists owe not only their style but an entire method of processing black-and-white images — high contrast, richly detailed, figure-oriented — to Foster. Which makes the perennial discontented-nerd argument about whether his work really “counts” as comics, because it doesn’t have speech balloons and sound effects, even more unnecessary than such arguments usually are. Of course it’s comics — but a specific, almost sui generis form of comics that demands that the reader exercise somewhat different muscles than all other comics require. Prince Valiant is best read with a sort of suspended urgency, neither the headlong rush of more explicitly cartoony comics nor the patient sentence-by-sentence derivation of prose, but a middle way between the two. It is not, by our current lights, a perfect fusion of image and text — when Sir Gawain falls into a washbucket, bringing a clothesline down with him, we don’t need to be told that that’s what’s happening in a caption just below the picture — but the slowing-down that such a caption requires forces us to linger over the image, to participate in the ongoing reconstruction of the scene before us rather than passively watching it unfold, as we would a movie or a play. It’s a technique that recalls the swashbuckling movies which were no doubt Foster’s most immediate form of inspiration: the dozen films Errol Flynn made with Michael Curtiz, in which action was underlined through dialogue, because otherwise the ten-year-old boys who were the movies’ primary audience might not be able to keep up. When Foster works his plot into its highest pitch, one can almost hear the Erich Wolfgang Korngold soundtrack.

It’s those same ten-year-old boys (and girls) who would be best served today by an introduction to Foster’s cleanly-drawn, rainbow-tinctured world, who would honestly thrill to the heroic adventure and honestly laugh at the goofy comedy and honestly shiver at the cartoonish evil of the villains. If I’m able to do it, it’s because I’m half-reading through my ten-year-old self’s eyes, the self who checked a pair of Prince Valiant books out of the library in the late 80s and read them again and again, and cut the John Cullen Murphy version of the strip out of the Sunday newspaper, and when there were no more to read took over my father’s Macintosh II and wrote my own medieval adventure stories starring a slim, black-haired youth and his pretty young love interest. By which Foster was yet further flattered.

But revisiting the series as an adult, I find myself most interested not in the characters, who are ciphers on which the young audience should appropriately project themselves, but in the gorgeous art (of course) and in the subtle sensible humanism that Foster encourages. There are dragons — but they are meticulously-researched leftover dinosaurs, not mythical creatures. There are giants — but they are genetic mutants ostracized by their fellow humans, not a different race on a larger scale. Even the magic of Merlin and Morgaine le Fay in the first volume is more symbolic and scientific than the traditional Faerie of the Arthurian legends. Foster is a man of the scientific, sensible twentieth century, and his world reflects that.

Up to a point, anyway. The long seqence in which Valiant and his friends chase the barbaric Huns out of Europe is frequently horrifying in its Yellow Peril racism. All of Foster’s villains are enjoyably evil; but the Huns are depicted as a degenerate race, incapable of humanity. Anyone who’s spent time with British adventure stories of the early twentieth century will recognize the ignorant stereotypes he’s drawing from, but that doesn’t make them any more palatable.

Up to a point, anyway. The long seqence in which Valiant and his friends chase the barbaric Huns out of Europe is frequently horrifying in its Yellow Peril racism. All of Foster’s villains are enjoyably evil; but the Huns are depicted as a degenerate race, incapable of humanity. Anyone who’s spent time with British adventure stories of the early twentieth century will recognize the ignorant stereotypes he’s drawing from, but that doesn’t make them any more palatable.

Still, they’re drawn with consummate skill. Fantagraphics has always been the industry leader in getting old comic strips back into print (at least since the dissolution of Kitchen Sink), and while their Prince Valiant reprints from the 1990s were wonderful at the time, this new edition is the best the strip has looked since it was originally printed on Sunday broadsheets in the 1930s and 40s. With Foster’s original colors — and he was as brilliant and forward-thinking in his use of color as he was brilliant and medium-changing in his black-and-white drawing — and a strong, heavy binding, these are archival editions, the sort of books that should be passed down to the next generation. I’ll be buying each one as it comes out, death and bankruptcy permitting. If you have any taste for this sort of thing, you should do the same.

Tags: Fantagraphics, Hal Foster, newspaper strips, Prince Valiant