Elmer

Reviewed by Will Morgan 25-Apr-11

We’re in the present day of a world where, back in 1979, chickens suddenly developed sentience, becoming the intellectual peers of humanity, and causing social and political chaos as they fought for freedom – and the humans, terrified by the revolt of a lucrative food source, fought back.

CHICKS? DIG IT.

CHICKS? DIG IT.

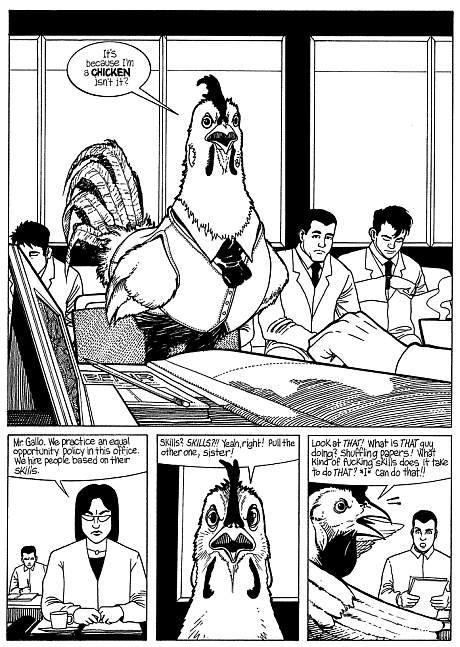

We open with scenes from a morning in the life of one Jake Gallo, young, unemployed, kind of a slacker. Insomniac Jake browses the internet and finds salacious photos of a former child star, now all grown-up, which helps him ‘get to sleep’ – in fact, to oversleep, so that he has to frantically rush to a job interview, where he throws a strop and alleges discrimination when he doesn’t get the position.

All well enough done, clear and mildly entertaining, but so far, so what? You might reasonably ask.

Well, the difference is, Jake’s a chicken.

No, I don’t mean chicken as in coward, but chicken as in barnyard fowl.

We’re in the present day of a world where, back in 1979, chickens suddenly developed sentience, becoming the intellectual peers of humanity, and causing social and political chaos as they fought for freedom – and the humans, terrified by the revolt of a lucrative food source, fought back.

Now, years after ‘The Awakening’, the sentient chickens have been granted legal status as an honorary offshoot of humanity, with equal rights under the law – but, of course, legal equality, as members of any minority know, does not necessarily result in a level playing field.

Gerry Alanguilan has a long career in comics, both in his native Philippines (where Elmer was published as a mini-series in 2006-2008) and in the US since 1995, where he’s worked primarily as an inker on titles such as X-Men, Fantastic Four, Wolverine and Batman.

None of his previous body of work quite prepares the reader for this.

Yes, ‘sentient chickens’ is, on the face of it, a ludicrous concept. They’re presented as interacting with humans in a same-size environment, and for the first few pages after the ‘big reveal’, you’re left with all sorts of niggling questions, such as how do they use the vehicles and artefacts designed for humans? Hell, Jake’s a writer; how does he even write, with wings instead of fingers?

But a few pages later, those questions have faded from your mind entirely, because you’re caught up in the narrative, and the strength of the characters makes the ridiculous premise inexplicably credible.

Alanguilan presents a story on two levels; one, a family drama, as Jake is summoned back to his childhood home, where he, his sister and his brother have to deal with the sudden, and ultimately terminal, illness of their father Elmer.

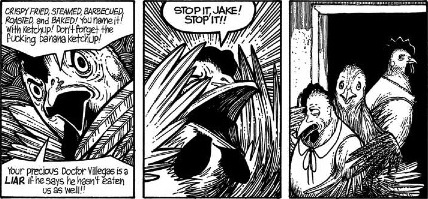

The second narrative, as Jake reads Elmer’s journal, is the story of what happened immediately after the Awakening: it’s a harrowing account of a people’s struggle, first for survival, then for equality, against an oppressor who regarded them simply as things to be eaten.

In making his protagonists poultry, Alanguilan has cleverly created the ideal ‘Everyman’ for his audience; owing no allegiance to any human ethnicity, the chickens are perfect identification-figures. Any reader can ‘relate’, without the inhibition of their previous cultural background, to Elmer and his comrades as they face the issues of enslavement, liberation, discrimination, grudging acceptance, and inter-species romance.

The cleverness of that concept, though, would be ineffective without Alanguilan’s considerable skills in telling the story; chicken’s faces, after all, do not inherently lend themselves to a wide range of emotional nuances, but he manages to convey their feelings with integrity and at times surprising power.

The cleverness of that concept, though, would be ineffective without Alanguilan’s considerable skills in telling the story; chicken’s faces, after all, do not inherently lend themselves to a wide range of emotional nuances, but he manages to convey their feelings with integrity and at times surprising power.

It’s one of those stories that, in the bare-bones synopsis, sounds silly and contrived. In fact, it’s an insightful tale that skilfully disables the reader’s preconceptions and gives the audience a true point of empathy.

Tags: Gerry Alanguilan, Slave Labor