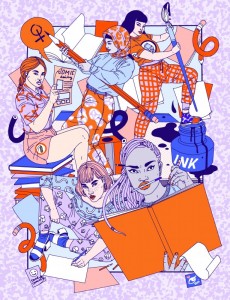

Comix Creatrix: 100 Women Making Comics

Reviewed by Tony Keen 20-Feb-16

“Comix Creatrix: 100 Women Making Comics” is a very impressive exhibition. Go and see it.

It can be all too easy for people to see the history of the comics medium, and often its current state, as largely a boys’ thing, both in terms of the creators and of the consumers. Last month, Franck Bondoux, executive officer of the Angoulême International Comics Festival, attempted to defend the lack of any female nominees for the Grand Prix by saying that women weren’t really important in the history of comics.

The central message of “Comix Creatrix”, which runs in the House of Illustration in London until 15 May, is that anyone who thinks this is wrong wrong wrong. The exhibition, co-curated by the House of Illustration’s Olivia Ahmad and British comics guru Paul Gravett, gives you one hundred women creators, represented by one or more pieces. There’s original artwork, reproductions, and some pages from comics of historical value. The creators represented include most of the ones you’ll have heard of – Posy Simmonds, Alison Bechdel, Kate Charlesworth, Carol Swain, Carla Speed McNeil – and several who may well be new to you. There are, however, some omissions, most notably Marjane Satrapi of Perseoplis fame, who is mentioned but not represented by any pieces – presumably the curators were unable to secure anything.

The first room establishes how deep in the history of graphic illustration women are embedded, beginning with Mary Darly, one of the earliest caricaturists, who was working at the end of the eighteenth century. There’s prominent space given over to Marie Duval, co-creator and artist of Ally Sloper (I hadn’t been aware that Ally Sloper was drawn by a woman – it’s not often mentioned). There’s a couple of charming pencil pages from Moomins creator Tove Jansson, with dialogue in Finnish, and in English underneath the panels. This room also illustrates the steps that women needed to go to to conceal their gender from the readership. “Blackjack” drew Tijuana Bibles under a pseudonym (it’s still not known who she was); Anne Harriet Fish signed her work simply as “Fish”; Tarpé Mills had to drop her first name, June; and Angie Mills was credited under her initial (though, in fairness, so was her then-husband Pat). And there are further examples.

The next room details the explosion in women creators in the 1960s, on the crest of the underground comix movement, with pioneers such as Trina Robbins and Aline Kominsky. It then takes the story through diversification into all sorts of comics and genres, all the way up to more modern creators such as Emma Vieceli. The range of creators and subject matter shown here is impressive. It is notable that there is very little superhero work on display, though there is a page of Supreme: Blue Rose by Tula Lotay. And there’s a nice page of Ramona Fradon’s Aquaman in the first room. There’s a healthy proportion of international creators, i.e. non-Anglophone.

The next room takes a more thematic approache. One side directly addresses women’s role in sexually explicit comics work, with examples from the work of Julie Doucet, creator of Dirty Plotte, and of Lynn Paula Russell (also known as Paula Meadows). Facing that are some of the more surreal uses of the comics medium that have emerged from women creators. A final room includes some video interviews with creators.

If I have a criticism, I would say that it is a shame that there is a concentration on female artists and female writer/artists, and little on women who write for other artists to draw (e.g. Jenni Butterworth, Louise Simonson, and more recently Kelly Sue DeConnick, Gail Simone and G. Willow Wilson). There are a couple of pages by the likes of Rhianna Pratchett and Emma Rios, but these are here to illustrate the female artists who drew the material. Such a bias is inevitable and understandable given the host institution’s mandate to focus on illustration. But it does give the slight (and wholly false) impression that women draw comics, but they don’t write them, or at least, not for other people.

One thing I particularly like is that the exhibition has shelves in which are placed collections of the work of some of the artists illustrated. So, for instance, below the original page from Posy Simmonds’ Tamara Drewe there is a copy of the published graphic novel, so visitors can get a better idea of context and the breadth of the work.

One thing I particularly like is that the exhibition has shelves in which are placed collections of the work of some of the artists illustrated. So, for instance, below the original page from Posy Simmonds’ Tamara Drewe there is a copy of the published graphic novel, so visitors can get a better idea of context and the breadth of the work.

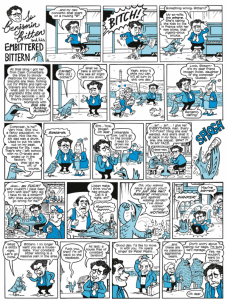

There are many highlights to be found here. Seeing the original artwork is delightful. I particularly liked a page of Lily Renée’s original artwork signed to Trina Robbins, and finding a couple of pages of Rachael House. And there was Laura Howell’s Sir Benjamin Britten and his Embittered Bittern, from Viz! (as if there was any question with a name like that), which put a huge smile on my face. But I barely scratched the surface. And it is worth emphasising how much this exhibition can function as a guide to waht you ought to be reading – there are plenty of works with which I was not familiar but which I would now like to chase down.

This is an exhibition that demands repeated viewings to get the most out of it. I have already been twice, and shall certainly return. And you should go as well.

For iPad users, there is also a free guide to the exhibition available from Russell Willis’ Sequential site.

Tags: Comix Creatrix, Exhibitions, House of Illustration