So-Called Critic: Sinner 4

by Martin Skidmore 12-Sep-11

If you were asked where, in comics, you might look to find out what New York City’s like, you might reasonably struggle for a satisfactory answer. Carlos Sampayo and José Muñoz are strange choices for this non-existent contest. Argentinians who, at least when their Joe’s Bar and Alack Sinner stories were created, had never so much as visited New York, their vision must surely arise from fiction, perhaps mostly from American movies, and thus can’t be taken wholly seriously. Nonetheless, their portrait seems far more persuasive than even those of the city’s most talented and devoted natives, like Frank Miller or Will Eisner.

[One of the things we want to do with the relaunched FA Online is to republish some of the best of Martin Skidmore’s writing on comics. We begin with this piece, from FA 114 (October 1989). By this point, Martin had developed his ‘So-Called Critic’ column, where he could give more detailed coverage to a comic than would be possible in a simple page-long review. This example discusses what Martin called “the exceptional fourth issue of Muñoz & Sampayo’s Sinner”. It’s a magnificent piece of writing, that shows Martin at his best. He spends a page talking about his own experiences of the fictional and real New York before he really gets into talking about the comic – yet that page is essential to understand his critique of the work. He also chooses to ignore completely what others have noted as a key feature of this story, the flashbacks to Alack Sinner’s own Vietnam past – that’s just not what Martin is interested in talking about here.

[One of the things we want to do with the relaunched FA Online is to republish some of the best of Martin Skidmore’s writing on comics. We begin with this piece, from FA 114 (October 1989). By this point, Martin had developed his ‘So-Called Critic’ column, where he could give more detailed coverage to a comic than would be possible in a simple page-long review. This example discusses what Martin called “the exceptional fourth issue of Muñoz & Sampayo’s Sinner”. It’s a magnificent piece of writing, that shows Martin at his best. He spends a page talking about his own experiences of the fictional and real New York before he really gets into talking about the comic – yet that page is essential to understand his critique of the work. He also chooses to ignore completely what others have noted as a key feature of this story, the flashbacks to Alack Sinner’s own Vietnam past – that’s just not what Martin is interested in talking about here.

The captions to the illustrations are Martin’s own. One final note: when Fantagraphics reprinted this series in English, they referred to it simply as Sinner, but every other printing uses the full title of Alack Sinner. – TK]

If you were asked where, in comics, you might look to find out what New York City’s like, you might reasonably struggle for a satisfactory answer. Frank Miller captures it pretty well, dirty and glamorous, something like if Chandler had lived there instead of in California perhaps, but it’s fundamentally implausible; it’s effectively impossible to imagine being there. Miller’s version is a fiction, marvellously appropriate to his super-adventure stories, but no more congruent with the real city than Batman or Daredevil could be conceived of as real people. Maybe Will Eisner would be the popular choice of many informed comics readers. He has, after all, spent a very large portion of his modern career cartooning, directly or indirectly, specifically about life in New York. But with Eisner, whilst it’s easy to believe he’s correct about the old days, it’s impossible to consider his work too useful as a representation of New York as it is now.

Carlos Sampayo and José Muñoz are strange choices for this non-existent contest. Argentinians who, at least when their Joe’s Bar and Sinner stories were created [in the 1970s and early 1980s – TK], had never so much as visited New York, their vision must surely arise from fiction, perhaps mostly from American movies, and thus can’t be taken wholly seriously. Nonetheless, their portrait seems far more persuasive than even those of the city’s most talented and devoted natives, like Miller or Eisner. Still, that’s just my view, the opinion of someone who’s spent about ten days in the city. I don’t know whether Sinner’s editor at Fantagraphics, Kim Thompson, knows it any better or not – sure, he’s American, but we mustn’t forget that the West Coast, where he resides, is about as far from New York as Britain is. In Amazing Heroes 160, Kim describes Muñoz and Sampayo’s New York as “semi-mythical”. Maybe he’s right. After all, surely the version of New York which has most profoundly lodged in my mind is not the two visits of the last year-and-a-bit, but, like Muñoz and Sampayo, that of American movies, TV and literature. Maybe they’re just striking the right chords with my media-distorted, semi-mythical image, rather than any sort of experienced reality. I’d be interested in the views of our New York readers on this…

On my first visit to New York, I was picked up at JFK and driven straight to Brooklyn. It immediately looked like a Will Eisner comic – “He was right!” I thought. But as days passed, I saw few of the Jews and Italians whom Eisner would have us believe are the inhabitants, and lots of Hispanics, Chinese and Afro-Caribbeans, whom Eisner virtually ignores. Other places made me recall other visions – I thought of Woody Allen in the Museum of Modern Art, but his upper-class intellectuals are only a tiny facet of the city, and one I didn’t substantially encounter (the only conversation I struck up in that gallery was not with some Manhattan intellectual, but an elderly woman from Scotland). On Lexington Avenue, I recalled the Velvet Underground’s ‘I’m Waiting For The Man’, but saw no pushers. Memories of endless films and TV shows set in Central Park proved hollow – neither a beautiful romance nor streams of murderous muggers appeared. Only two of my cultural reference points stood up to an actual visit; the songs of Tom Waits and the comics of Muñoz and Sampayo.

I think exploring Tom Waits’ portrayals of the seamy side of American (emphatically not just New York) life here would be too much of an indulgence, but the recent publication of the extraordinary fourth issue of Sinner seems a good opportunity to take a look at Muñoz and Sampayo’s work.

It’s both quantitatively and qualitatively different from previous issues; at 38 pages, it’s virtually as long as the stories from #2 and #3 put together, and it departs from the traditional private eye cases related in the first two tales (#1 featured later material). In #2’s ‘The Webster Case’, Alack Sinner, private detective, confronts the hostile police captain, is hired by a scared, wealthy man and gets involved in a murder case; #3’s ‘The Fillmore Case’ has a slightly quieter prologue (with Chandler’s The Big Sleep prominent in the first panel) before he’s hired to protect a rich man, then the murders start, and so on. On a formal craft level, they’ve got a great deal going for them, and the stories are interesting enough, but frankly the back-ups are more worthwhile than the lead Sinner tales: 9 pages of Sudor Sudaca by Carlos and José in #3, one of a later series set in Latin America, and ‘The Slaughtered Chicken’, a nine-pager by Alberto Breccia, South America’s finest cartoonist, and one of the world’s greatest, in #2.

Issue 4, featuring the third Sinner tale, ‘Viet Blues’ (note the change in the title style) is quite different. In the opening pages, Alack rescues a black kid being beaten up by two big black men, before the police arrive, ask Alack why he wants to “get mixed up in that—nigger business?” and try to arrest the victim before deciding to ignore it; then the kid refuses Alack’s offer of help – “it’s nigger business,” reiterated. This might easily be read as a prologue, similar to the opening structures in previous tales, especially when a dwarf turns up with a missing wife for Alack to find. Ah, dwarves, circuses, a mystery – this seems much more like the start of a Sinner case than some black kid in a fight, a scene apparently intended to establish Alack as a white (!) knight figure. But no, the dwarf’s case is disposed of within two pages, whereupon the black kid, John Smith III, gets back in touch, and we see he’s a blues pianist. The beating is still “nigger shit” and we’re not drawn into any mystery, nor given any real hint of there being a job for our protagonist, but this quick return does at least clue us into what this story is about, and puts the dwarf’s two pages into perspective as a thematically linked interlude; it turns out he had been beating his wife, resenting her previous marriage to a black man.

The plot turns out to be about a big drug dealer trying to get revenge on the man who put him in jail some years before – Smith is a friend of that man, and when Anita Smith, his wife, is killed, Alack gets seriously involved. Beneath all this, what the tale is really about is the relationship between black and white people in New York – a complex and challenging subject far more suited to this team’s great talent than the more straight genre material of earlier tales.

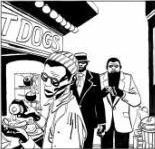

Black people, early on, are shown with white signifiers of ‘degradation’ tacked on; John Smith III turns out to be a heroin addict, and Alack gets set upon by a trio of black muggers with knives and chains. I was highly uneasy at this point; our white hero coming to the rescue of a pathetic black junkie, heroic despite these blacks not really deserving it? But of course my misgivings were completely baseless: Smith was started on heroin by a vicious white sergeant in Vietnam; the big pusher, ‘Blade’, who killed Anita, is black but, as Alack says, “He thinks like a white man” (and his eyes are “one of each color” – whatever that means). When we eventually meet him, he appears to represent the worst excesses of capitalism, claiming he offers “society what it wants from me; nothing more,” and invoking private enterprise as some kind of almost religious unquestionable justification for dealing in heroin. This is particularly apt, as there’s a powerful case for considering heroin the ultimate capitalist product: fundamentally useless, very expensive, creating its own escalating demand by its addictive qualities, and pacifying the proletariat by making them too out of their minds to present any effective opposition to the ruling class. Incisive characterisation, therefore, but not necessarily congruent with the claim that he “thinks like a white man.” Capitalism is by no means a uniquely white preserve.

The parameters defining the relations between the races are described powerfully throughout. In contrast to the opening scene of police indifference, and their assumption of the victim’s guilt, when Alack is getting mugged the discovering police notice “Hey, that’s a white guy they’re beating up on!” “Let’s go!” The muggers flee at their approach, and the police shoot, and kill, a 15-year-old black kid in the back. Their action is considered legitimate self-defence by the authorities. When Alack wakes up, he meets a black doctor, who calls the muggers “the shame of our race,” and believes “They ought to be sent back to Africa.” A black nurse, however, says “The cops killed a 15-year-old brother on your account. Watch your ass, white boy…”

Likewise, Olmo, a friend of Smith’s, points out to Alack that “the days are over when brothers needed white Samaritans to bring civilisation to them.” Later, when Alack is trying to tell Olmo that “Your enemies are my enemies too… I don’t believe in the law any more than you…” Olmo replies, correctly, that “we do. We believe in its existence. We know it’s the weapon of the ruling class, and we try to destroy it.” Ultimately, the black radicals are right in believing Alack can never truly understand, that his colour is a barrier.

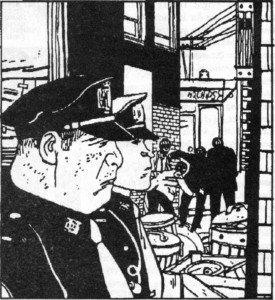

Great compositions are one of the artistic strengths that carry Sinner 4 above being just a competent genre story

Alack gets to be the hero in just one segment, after the initial rescue: with Loretta Parker, a character returning from #2’s ‘The Webster Case’ – she was Webster’s art director – he nurses John Smith III though his withdrawal from heroin. Still, it’s hard not to read this as white paternalism – white people helping a black man kick a habit he got from a white man (one part of the establishment, the army, too, of course). Likewise, the initial rescue is later matched in reverse, when Alack has been captured by Blade, and is being tortured for information, a group of masked blacks (including Olmo) breaking in to kill Blade incidentally rescue Alack in the process. Honours are even in this sense, but it’s the blacks’ action which is, perhaps, more meaningful. As Olmo says to Alack (in a scene in Joe’s Bar – this and Loretta’s reappearance are two manifestations of the extraordinary, casual coherence of the vision of these creators): “You’re naive and guilt-ridden. You fight the symptom, not the disease. Okay, so John kicked the habit. While he kicked it – at the very moment he was kicking it – one hundred other black men started their long march through junk.” Still, even ignoring Olmo’s questionable, made-up figures, it’s doubtful we should consider pushers the disease; I can’t recall who, but someone pointed out that you can’t prevent suicide by abolishing rope. Likewise, Olmo is no more addressing the deprivation and alienation which drives people to dangerous drugs than Alack is, although at least his action may mean there’s less of the stuff around for a short while.

There are many indicators of the stress between the races on show here: we see Alack not getting served in a black club, then a couple of pages later, leaving the same club. Alack and a black man are frisked by a group of police, for no reason – it ruins Alack’s night, but the black guy just wants them to “make it snappy”. The routine nature of police harassment of black people is painfully evident here. And there’s one moment where the creators suggest, correctly, that the central thrust of their commentaries on racism is also applicable to prejudice against homosexuals, when Alack gives a young gay man a lift (he only lasts a few panels before being shot). It’s a bit of a shame that they couldn’t link sexism in, too, as this is a story dominated by males, but I suppose we can’t have everything. The effective examples of police racism are brilliantly topped off when Blade’s two thugs beating Alack up (they also killed the gay man) turn out to be ex-cops. There is no suggestion that they’ve ‘gone bad’: it’s simply that Blade pays them better…

Sinner 4 is a strong story, with an interesting plot and good action, but the constant power of its thematic content is quite exceptional. And on top of that, there’s the artwork which, other than in the ways it expressly reinforces the theme or forwards the story, hasn’t yet been mentioned.

Muñoz is an exceptional talent, developed by exceptional teachers. He studied, in Buenos Aires, under Hugo Pratt and Alberto Breccia, unquestionably two of the greatest masters of the medium ever, and their strengths and approaches are quite noticeable in Muñoz’s work. Both these teachers eschew pyrotechnical layouts or flashy images, both have drawing styles that often look scrappy at first glance. Likewise, Muñoz sticks throughout this story to three tiers to a page, with one to three panels per tier. All rectangles. And there is no sense of polish in his line, no fine rendering. He uses coarseness to fit his milieu. Lines are rarely smooth, shading is in blotches of black or rough lines, but he draws very well indeed, and captures atmosphere and expression with a wonderful, casual grace. Everything looks precisely right, in the roughest alleys of Harlem or the elegant homes of the rich.

And his boldness of drawing serves his outstanding virtue, his consistently superb, often striking composition. Covers to this Fantagraphics series are generated by enlargement, to a great degree, of interior panels. A while ago, I was discussing Muñoz’s co-mentor, Hugo Pratt, with Dave Gibbons (sorry to name-drop), and he mentioned seeing slides of some of Pratt’s panels, blown up to several feet across, and how the magnificence of his composition was considerably more evident there. This was a good observation; enlargement is an excellent test of good composition, and Muñoz’s art passes with flying colours. Ignoring for this purpose their relevance as representatives of the story, I looked through ‘Viet Blues’ considering each panel’s visual impact when enlarged to go on a cover. Obviously many are entirely the wrong shape, but, although on #4 a whole panel is used on the cover, on #2 a wide shot is turned into a wraparound, and on #3 a panel is cropped on left and right edges. Therefore, it seemed fair to ignore consideration of shape. Panels, for example, which close in on Sinner’s face occasionally failed to cut it in my mental game, but I would estimate that something like 90% of the panels are held together so well, have such a well-judged balance of dark and light and such a solidly dramatic structure to them that they would grace a cover.

Even at this relatively early stage of his career, Muñoz is an outstanding artist, with a quite impeccable cinematic narrative sense, which flows so well one doesn’t even notice it, and a sense of place so complete and detailed that it’s impossible not to be convinced by its vision. Maybe it is derived from the cinema, rather than direct experience, but, finally, that matters little. The result is a compelling portrait of New York in this, the best issue yet of a series which must rank as one of the most appealing and praiseworthy being currently printed in English.

Tags: Carlos Sampayo, jose, Jose Munoz, Martin Skidmore, Sinner

Muchas gracias, muchachos

Thanks a lot, guys)

It’is, it was, an inmense pleasure havin’ been able to touch your souls that way, I’m a little bit drunkard tonight, drunkard till the right point, or maybe the left point, of being near to the usual old age tears…Whatta wonerful’ wérld, sometimes.

We’re very glad you liked this piece. Martin always rated your work very highly, and I’m sure he’d very much have appreciated your comment.

Oh man I am SO GLAD I found this site!!! I remember finding this issue of FA (that stood for Fantasy Advertiser, am I right?) in a box of comics in a local bookshop in about 1990, I seem to remember the issue having a green cover and a Russ Manning drawing of magnus (maybe I’m confusing it with another smallish Brit comics periodical?!?), it was a good five years before I got into “alternative” or underground comics but I ALWAYS remembered this brilliant piece of writing and was eventually able to buy all the Fanta issues of Sinner in one fell swoop in the late ’90’s. At the time I found the FA my main comics passions were Steve Rude, the Grant/Breyfogle Batman and 2000AD, I would’ve been 11, 12; but that art in the Sinner piece grabbed me by the balls, HARD! And I remembered the style and the name of the artist immediately when I saw those five Fanta “Sinners”, all with my name on ’em!

I also seem to remember a really scathing review of an issue of A1 in this issue of FA going so far as to refer to Dave “Funky” Gibbons(!!!) being a boring and predictable artist, a review of the Marc Hempel comic about the kid in the mental hospital and I’m pretty sure there was a big Paul chadwick interview with some tidbits about Yummy Fur and Hugo Tate in the back?

Again, I might be conflating publications in my memory, here, but I definitely remember the awful A1 review and of course this wonderful piece. I didn’t even know who Tom Waits or the VU were, then.

Unfortunately the issue of FA got lost, much to my devastation….if the administrators can supply me with some answers about cover features, etc, it will cease many years of frustrated wondering!

Munoz and Sampayo are one of the best writer/artist teams to ever grace this glorious medium.

Thanks for the memories!

All the best,

Ant

I actually found the issue in question yesterday sandwiched between a few old “Mojo” magazines! Completely by chance, I thought it was long gone (no cover though, alas……)!