Death Note

by Martin Skidmore 18-Dec-10

There are gods of death watching over this world. They each have a notebook, in which, when any name is written, that person will die. One of those gods of death, in search of entertainment, drops a notebook into the human world.

by Tsugumi Ohba & Takeshi Obata

by Tsugumi Ohba & Takeshi Obata

There are gods of death watching over this world. They each have a notebook, in which, when any name is written, that person will die. It even allows control, within clear rules, of when and how, and what they do that leads to their death. One of those gods of death, in search of entertainment, drops a notebook into the human world. It is picked up by Light Yagami, a brilliant young student, who soon determines that the rules written in the book are true. He decides this gives him the power to punish evil people, and change the world for the better. The authorities notice the increasing flow of inexplicable deaths, especially when it becomes worldwide. Investigations get nowhere, and the UN calls in the mysterious but infallible detective known only as L, who soon narrows his search.

This 12-book series really takes off when L’s search focusses on Light, who is the son of the top cop involved in the case. The detective work is convincing and very smart. But Light is a genius, Japan’s smartest student of that year, and he has the advantage of the book and hacked access to his father’s data, so he doesn’t make it at all easy. He even manages to get taken into the investigative team and to meet the reclusive L.

There are lots of things to love about this series, but for me what makes it a very special joy is the battle between L and Light, as the former tries to work out how this is all happening and to prove it is Light doing it, and Light tries to discover L’s real name so that he can write it in the book and remove the one obstacle that could prevent him from becoming god of a new world.

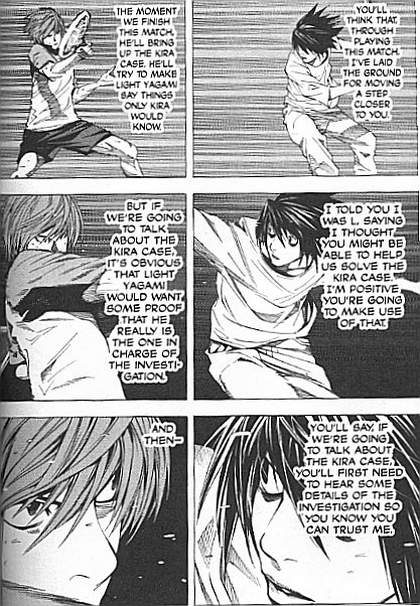

Clearly it’s easy for a writer to tell us someone is a genius, and too often this just means they can whip up whatever invention a plot requires. Even with detective work, the writer knows what happened and can slide tiny clues that are almost impossible for the reader to put together, to convince us how clever the hero is. Here Ohba has set himself a far tougher challenge: we follow both geniuses, and see their thoughts. Both are manoeuvring with immense skill and originality to achieve their ends, and trying to second-guess the other. Light has to appear to help L and the rest of the team, has to react in the ways L would expect of him if he isn’t behind the deaths. It demands an extraordinary agility of intellect from the writer, and he impressed me enormously time and again, as each reads the other’s ploys and moves to counter them, and I didn’t spot a single instance of cheating, either where someone shouldn’t have been able to deduce or predict something or where someone should have realised something but didn’t.

Ohba also keeps the action rising in brilliant style, throwing new complexities at both main characters, most importantly including a second notebook, its new owner (a young girl) and the death god who loves her and will protect her from anyone, including L or Light. The story is consistently stimulating, always twisting in ways that delight and amaze and thrill, including some ploys that are so far beyond complicated that they take time to absorb and boggle at even after you have seen them revealed and played out in full. It’s quite simply the most intelligently written and inventive comic plotting I have ever encountered.

Ohba also keeps the action rising in brilliant style, throwing new complexities at both main characters, most importantly including a second notebook, its new owner (a young girl) and the death god who loves her and will protect her from anyone, including L or Light. The story is consistently stimulating, always twisting in ways that delight and amaze and thrill, including some ploys that are so far beyond complicated that they take time to absorb and boggle at even after you have seen them revealed and played out in full. It’s quite simply the most intelligently written and inventive comic plotting I have ever encountered.

And the art is wonderful too. Obata demonstrates all of the qualities you would ask of an artist on a story like this. He makes the death gods striking. He makes the many characters distinct personalities visually, and expresses their emotions with subtlety and control, a real challenge when they are hiding their real feelings. Many of his faces are a huge pleasure to see and watch, especially L’s, whose body language is also completely unique to him. Obata tells the story with a particularly noteworthy clarity, with varied and well-chosen page designs and sharp storytelling flow, without ever appearing to try to get flashy. In summary, the artist shows every sign of being as intelligent in his realm as the writer in his, and the work is cleanly gorgeous just to look at, in a porn-tendency-free Manaraish way – enough that I have bought another series with his art (a medieval fantasy with lots of dragons – not really my thing) just because I love it so.

I should note my one misgiving about this series: it reaches a magnificent conclusion in volume 7, but then rather starts again. I’ll avoid explaining what I mean for major spoiler reasons, but there is something of a reset at that point. Ohba is easily clever enough to carry this off in most respects, and there is plenty more brilliance and entertainment in the remaining books, but I understood it when the two superb movies, without following every detail of the manga story, basically chose to end it with that first conclusion.

The Death Note films really are excellent, by the way – everyone looks right, and there is plenty of the same intelligence. I’ve not yet seen the third film, which is a prequel about L and nothing to do with the notebooks or Light Yagami. The anime series (the only one I have ever bought, 37 half-hour episodes) is spot on too – obviously it’s straightforward for them to get the look right, and they basically copy the story in full too.

Tags: Death Note, Manga, Takeshi Obata, Tsugumi Ohba

I’m halfway through the third volume (just past the tennis match above), thanks to the local library. It’s a thoroughly entertaining read, if gratuitously explicit. Reminds me of advice I once read for screenwriters: “Tell them (the audience) what you’re going to tell them, tell them, and then tell them what you’ve told them.” This seems to happen a lot in Death Note. But then, with all that interior debating, perhaps it’s inevitable. Super read thus far, mind.

My prevailing memory of this series is its addictiveness. I recall gobbling each volume up voraciously and, when done, throwing it across the room in disgust at myself with a shame spiral setting in for the next hour or so. I’d begin the cycle anew a few days or a week later when my library got the next volume in.

It’s pure narrative engine and should either be lauded or outlawed. One day I plan on writing an essay on the joys of confusion and I imagine Death Note will prove central to it.

I have been meaning to get round to reading this ever since seeing a piece by Tom Ewing on it, where he was writing about it as the first Manga he had read. What I found interesting about it was the way the power given to Light had basically turned him into a monster, so I would be reading it to watch his slow slide into corruption.

I’d hate to disappoint you, but the moral ambiguity in Death Note lasts all of about three pages.

The joys of Death Note are not necessarily character-based; for all its facade of supernatural elements and neat-ass gimmick, it’s the pure narrative engine that gets you, watching two characters who are straight-up logic machines trying to second and third and fourth guess the other for the sake of winning winning winning (as is the classic shonen manga manner).

I think that’s a bit unfair – there are moral questions in the air from the start, when Light starts to use the book, and much of the way through, as he starts to use it for more than punishing criminals, extending its use to protecting himself, even if that means killing the good guys who are against him.

I recall, when reading, that alot of the fun came from watching all the moral quandaries get tossed out the window as soon as they popped up – they’re acknowledged for the sake of reader identification, but soon dismissed (along with lotsa civil liberties). Maybe I’m just secretly evil.

I suppose it’s a moral work in the sense that everyone in the book is pretty much a jerk and, in the long game, doomed. The only people that aren’t jerks are, well, female.

My ultimate impression of Death Note was watching a grand game of chess that you, reader, could totally identify with via awesome narrative alchemy on the part of the creators. Yeah, that’d work:

CHESS – BUT WITH SPEED LINES!

Oh yes, you’re totally right that the story’s engine is the intellectual battle, no doubt about that. But the public reaction and debate about the morality of his actions is always part of the story, and while you can sympathise with his approach at the start, his focus does shift towards protecting himself at literally any cost, and that is always a part of the story too. We are shown that his enormous amounts of murders actually does make the world a better place, so there is a question about ends justifying means, and about punishment for evil people.